Temples for Curious Minds

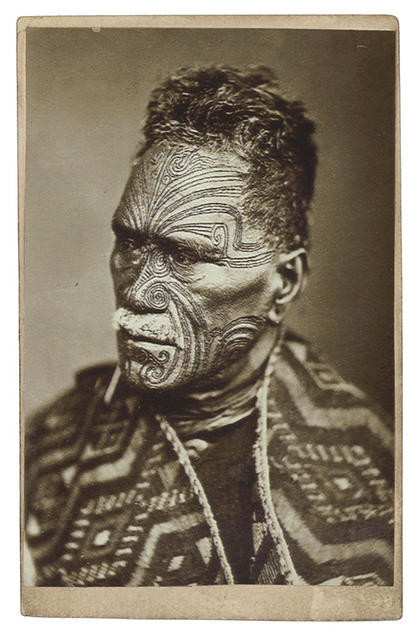

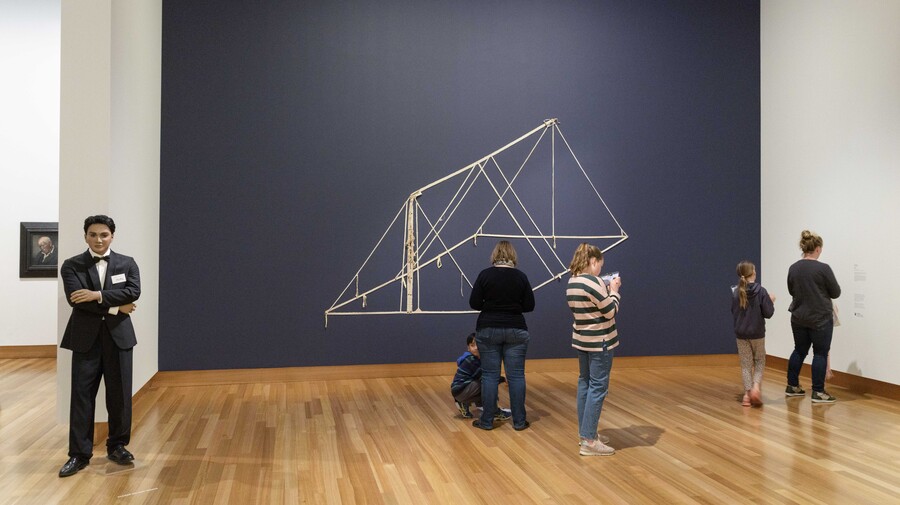

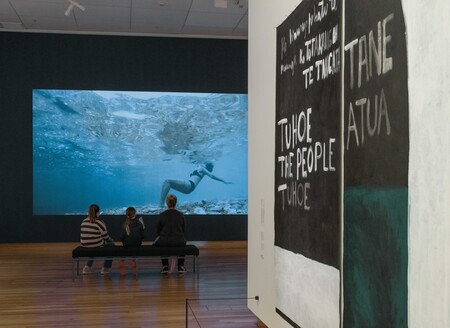

Te Wheke: Pathways Across Oceania (installation view) 2020. Photo: John Collie

I want to tell you a story. A ‘curiodyssey’ (which by the way, I thought I’d made up but is the name of an actual museum in California). So, a curiodyssey of happy places, told through the science of wellbeing.

Te Wheke: Pathways Across Oceania (installation view) 2020. Photo: John Collie

Galleries, museums and libraries are my happy places. They are where I have access to wonder and awe, to inspiration, hope, the myths and stories we tell ourselves. They are a mirror held up to society that may or may not answer the question: who is the fairest of them all—if only I dare to look.

Pretty much my favourite family outing as a kid was to Canterbury Museum. Some of my earliest memories are of walking towards that impressive Gothic stone building, and wandering its darkened halls with my siblings. A great, suspended rotating globe, drawers full of giant butterflies and spiders, buttons to push, a shaggy bison (don’t touch), a replica early Christchurch Street, Amundsen’s shiny bronze nose (don’t touch), a blue whale skeleton hanging like a giant, flying dinosaur. To me, at three-years old, animal skeletons were synonymous with dinosaurs.

Just as much as the exhibits themselves, I remember clearly the sense of wonder and awe at the spaces containing them. The peacefulness of it all. The quiet, low-lit sense of the exhibits waiting, watching me. The cool seriousness of marble and stone, the imagined whispers of stories from the past echoing behind glass cabinetry, a holy place of contemplation, a cathedral to curiosity.

Now I wasn’t conceptualising all this at the time, as a red-cheeked little barrel toddling around the halls and exhibits. But I’m sure my smile could be seen from the moon.

Why did these experiences make me so happy? What was it about the spaces and all they contained that was so formative that I am now a public health professional, waxing lyrical about the joys of galleries and museums. How much health is contained in these houses of curiosity?

Zoom many years forward. Now when I travel, I’m still seeking out happy places, the galleries and museums, from Okains Bay to Montreal. Places of wonder and inspiration. Temples for curious minds.

I’m still curious. I’m fascinated by human wellbeing and potential. By happiness and what it means to us and why. And how we can create it for ourselves and others.

Te Wheke: Pathways Across Oceania (installation view) 2020. Photo: John Collie

I study and work with concepts of human wellbeing, to understand it at an individual level and to promote and improve it at a population level, to kill the ignorance around mental health. What we now know about the psychology and neurophysiology of human wellbeing makes clear that our houses of culture, curiosity and history are essential elements of a flourishing society.

So what is wellbeing? The World Health Organisation describes optimal health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”.1 So how do we define and measure it instead of simply deeming people to be ‘not ill’? And if museums and galleries are some sort of curative, to what ailment are they the solution? Perhaps it is more of a lack that they address than a dysfunction. Perhaps they nourish and sustain, perhaps they provide essential vitamins and minerals for the production of wellbeing.

Positive psychology is the study of human wellbeing, when we’re feeling good and functioning well – trying to understand what it is and what causes and supports it. And luckily we now have a pretty good idea of what a flourishing human being looks like. Maybe like a ball of yarn is to a cat, it is endlessly intriguing, mysterious and, ultimately, a tangled hot mess.

So here is what wellbeing looks like. Across various schools of thought and research, these are the features of flourishing that seem to be core to good mental health, and they possibly won’t come as a surprise.

- Meaning and Purpose

- Engagement and Interest – experiencing states of flow and curiosity

- Positive Emotions – feeling joy, hope, love, amusement, accomplishment, friendship, belonging

Around these fundamental core experiences are further desirable ‘symptoms’: positive relationships, optimism, vitality, self-esteem, resilience and self-determination (a sense of agency). Having some of these most of the time, in addition to the core features, is considered, more or less in my grand simplification here, to be flourishing.

If we consider those core features again, what sorts of places or environments could help people experience these things? It seems clear to me that, at their best, museums and galleries are veritable engines of meaning, purpose, engagement, interest and positive emotional experience.

Looked at in the context of one of the most common mental health promotion messages, Five Ways to Wellbeing,2 it’s pretty much a big tick for galleries and museums.

A recent report from the National Alliance for Museums, Health and Wellbeing in the UK, notes:

[M]useums and their extraordinary spaces and collections inspire a number of less traditional health-promoting activities for body, mind and spirit. … Museum spaces carry a variety of resonances from the awe-inspiring to the cosy or domestic, but are almost never anodyne. Such affective atmospheres potentially invite creative responses.FTN-3

Te Wheke: Pathways Across Oceania (installation view) 2020. Photo: John Collie

In other words, they provide an evocative, sometimes provocative, environment that engages us, motivates us to become curious, interested and self-determining.

Another report from the UK, Creative Health,4 looked into the role of the arts and culture in health and wellbeing and describes “the immense potential for museums as accessible spaces for creativity and part of the public health milieu”. It goes on: “the arts can help save money in the health service and social care.” The report urges the UK’s ministers of Culture, Media and Sport, Health, Education and Communities and Local Government to develop and lead a cross-governmental strategy to support the delivery of health and wellbeing through the arts and culture.

Leading innovators in health policy internationally and right here, have advocated for years for health services that are wellbeing- rather than disease-focused, are “people-powered”,5 and offer “more thanmedicine”6 It seems clear that this is a need for change in our public health systems.

Here’s a quote from Polly Hamilton in the foreword to another UK report, People, Culture, Place: The role of culture in placemaking.

Culture holds up a mirror to our tired streets, squares, buildings and civic spaces and asks us to look again at what makes them special. It gives people the opportunity to connect their individual stories with collective narratives, helping to make their place feel like home. Culture provides people with ways to explore, celebrate and create shared experiences. It brings depth and meaning to people’s experience of a place, highlighting the extraordinary in the ordinary.7

I think curiosity heals us.

I think museums and galleries are engines of wellbeing.

I think galleries and museums are hospitals for the heart, the mind and the spirit.

But they are hospitals you don’t have to be ill to visit, and they will heal you regardless. Clinics for the well or the sick, the tired of spirit and mind. A sanctuary for those not particularly in danger or otherwise threatened, and for those just in need of the reassurance of a story, or the inspiration to live, change or create.

Like I said, my happy place.