Channelling

Wendelien Bakker Catching a Grid of Rain 2023. Steel. Courtesy of the artist

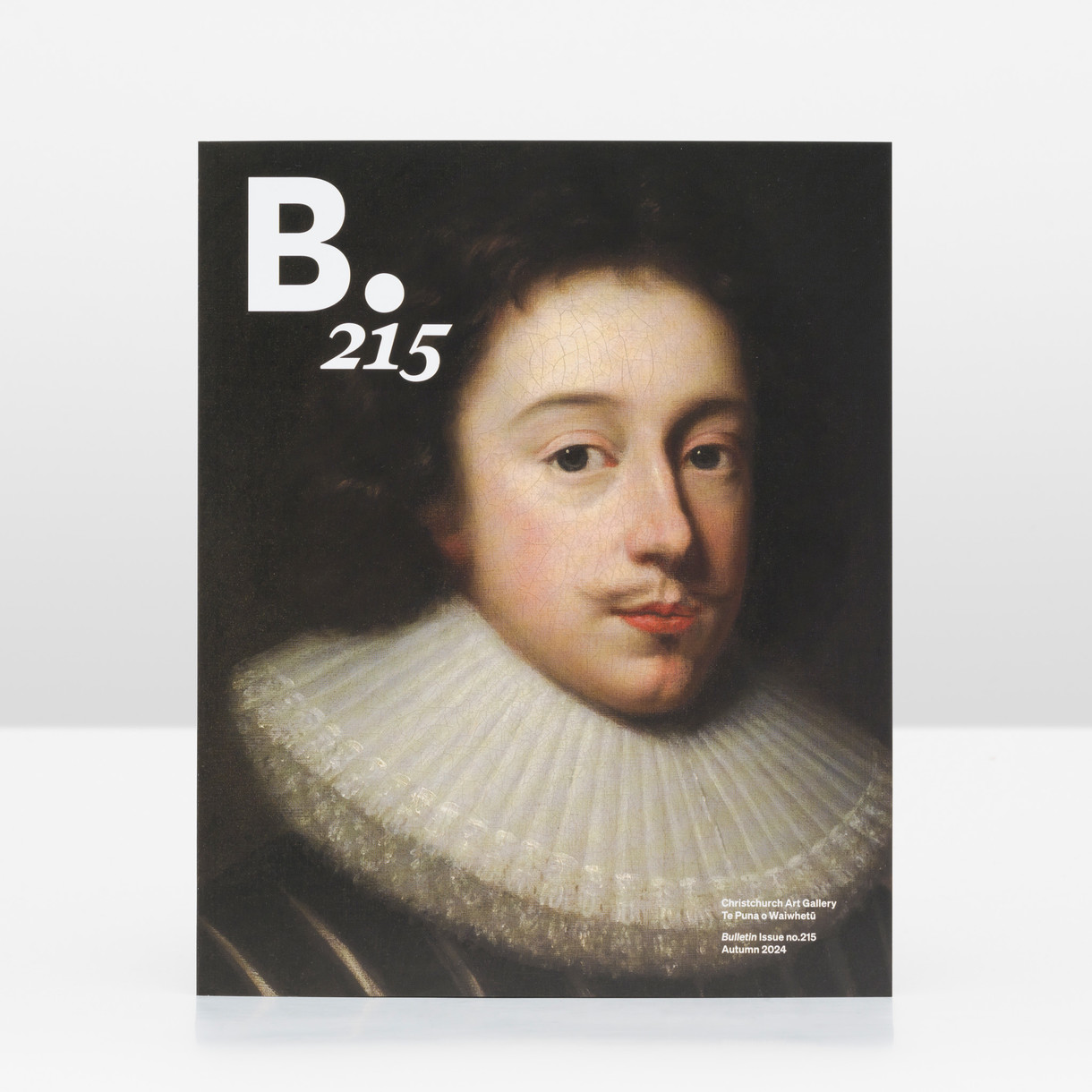

In this issue of Bulletin we invited writer and curator Simon Gennard to respond to the exhibition Spring Time is Heart-break. Simon delves into works by artists Wendelien Bakker, Madison Kelly (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Pākehā) and Lucy Meyle, which each examine complex entanglements across species and human/non-human relationships. Looking to the dynamic thinking of writer Ursula Le Guin, Simon offers another way of looking at these artistic practices, as a process of making kin within our contemporary world.

In trying to find a way into Wendelien Bakker’s Catching a Grid of Rain (2023), I have been thinking of follies. In architecture, a ‘folly’ refers to a category of building, popular among the landed classes of eighteenth-century Europe, whose primary purpose was to decorate sprawling country estates. The structures often reproduce ruins, temples or grand historical architecture in miniature. Many are out of step with their spatial and temporal surroundings – the lasting outcome of human endeavours to manipulate and impose intention, order or logic upon the world. What distinguishes the folly, however, is the honesty of its designation. The folly suspends any pretence of social utility beyond pleasure or light entertainment – for the individuals who commissioned these buildings, or those granted licence to access them. Architect Chris Perry writes that the “folly has been absolved of any and all normative architectural functionality.”1

I was thinking of the folly as a way to consider relationships between social utility, aesthetic value and architecture. Bakker’s work intervenes into an architectural given, less as ornament than provisional infrastructure. For Catching a Grid of Rain, she applied a network of steel channels to the roof and exterior walls of the concrete structure on the Gallery’s forecourt that covers an elevator shaft to the under- ground car park. The work functions as guttering, providing a pathway for rain that may fall within its boundaries, albeit more meandering than the direct line guttering usually provides. But as infrastructure, its use is limited, and the work’s title only tells half the story; once caught, the guttering releases the water at the base of the structure, and ushers it back into the earth.

The structure Bakker has adorned is half-affectionately known as ‘the bunker’ by the Gallery. As an architectural form, a bunker, like a folly, cares little for the complexity of the world it is situated within. Unlike the folly, however, the bunker has no use for aesthetic pleasure – whether in the service of military campaigns, or post-apocalyptic survival, its purpose is pure utility. Artists have previously been com- missioned to produce murals for the Gallery’s bunker, tasked with beautifying a structure described at various times, as “unfortunate”2 and “unsightly.”3 Bakker, however, was more interested in responding honestly to the building’s form, choosing to have plywood cladding stripped away and reveal the blocks of concrete aggregate that line it.

Wendelien Bakker Catching a Grid of Rain 2023. Steel. Courtesy of the artist

Within a built environment, water tends to appear either as a resource – for drinking or cleansing or a pleasant feature to walk beside – or as an imposition. The ongoing maintenance of a dwelling, or a city, relies on the effective distribution of wet and dry through a half-hidden network of gutters, drains, pipes, treatment plants and outlets; channel- ling water where it should go, and preventing its leakage into areas it shouldn’t. It amounts to the behavioural engineering of a substance necessary for the sustenance of life, and more creative than we could possibly know.

In conversation with the artist, Bakker mentioned she is interested in the agency of water.4 She is in the slow process of building a home on Banks Peninsula, and making the building watertight provides occasion for renewed attention to the creativity of water’s movement – travelling up between crevices, sideways and outwards along surfaces that should be flat. In Catching a Grid of Rain Bakker follows this attentiveness by intervening, ever so briefly, into a cycle of resource and usefulness, enabling a small amount of water to meander, to travel a path without purpose or to adhere to a slightly altered rhythm, before entering the city’s stormwater system.

Later in our conversation, Bakker expressed a brief concern that, having produced a path for rain to follow, the rain may not come.5 With the rhythms of weather more prone to extremity, to acting out of sync, to exceeding human predictions and best-laid plans, the possibility seems real. Which might serve to remind us that in granting a non-human substance agency to act as a participant in an artwork, we must be prepared for the possibility that it may not behave as we want it to.

The word folly is tangled up in associations with foolishness, stupidity, even wickedness, but as an architectural term, it may have made its way into English in the thirteenth century from the French folie, meaning ‘delight’.6 Delight might also describe the quality of Bakker’s attention to the creative movements of water. And it’s a word that tellingly appears in Ursula Le Guin’s essay ‘Deep in Admiration’, in which she argues for the capacity of poetry to ‘subjectify’ the universe and all the creatures and forces within it, thereby wrenching us from a relationship that considers these things as resources to be extracted, used up, disposed of. “Skill in living”, Le Guin writes, requires an “awareness of belonging to the world, delight in being part of the world,” and “tends to involve knowing our kinship as animals with animals.”7

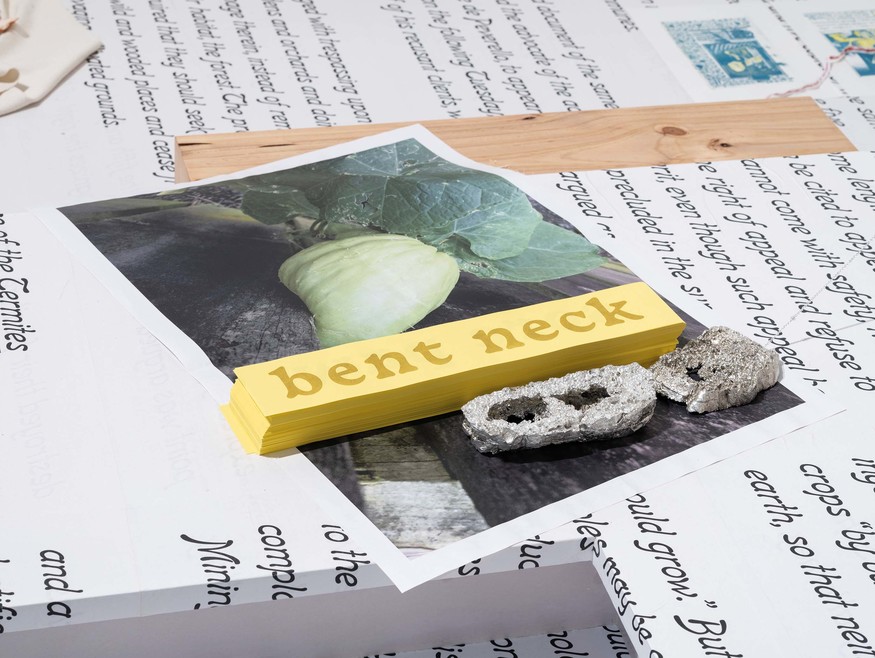

Lucy Meyle Every Green Herb for Meat 2023. Various materials. Courtesy of the artist

In her installation, Every Green Herb for Meat (2023) Lucy Meyle lingers on several historic examples of humans struggling to reconcile with the agency of the non-human world and, specifically, animals. Enlarged and printed on newsprint are excerpts from E. P. Evans’s book The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals, first published in 1904. In the book, Evans documents a number of legal and ecclesiastical trials of individual animals and entire species that took place in Europe during the Middle Ages. Cases range from a swine executed for infanticide, a cock burned at the stake for the unnatural crime of laying an egg, and the summoning of the caterpillars of the forests within the Italian province of Sondrio to appear before a court “charged with trespassing upon the fields, gardens and orchards and doing great damage therein.”8

Meyle’s newspaper covers a low platform, upon which sit several pieces of furniture. Each one is an approximation of an item found within historic depictions of Saint Jerome, patron saint of translators and librarians. A timber footstool from Lorenzo Monaco’s 1420 painting Saint Jerome in his Study; a pale yellow lectern reproduced from an icon (c. 1400–50) held in the British Museum’s collection; a book house from the psalter of Saint Jerome in a book of hours held by the British Library. These depictions of the saint and excerpts of defences of the creatures of the earth also appear on printed matter, which is scattered and assembled into neat stacks throughout the installation. It is as if we’re happening upon a private study belonging to someone caught mid-thought.

Meyle mentioned to me she was interested in thinking about how people find themselves stuck in postures.9 We can read this literally within the work. Across European art history, Jerome finds himself pictured with a stiff neck, head turned down, or else looking pensive. It’s the posture, more often than not, that identifies him. It sticks out. But there’s a posturing, too, in the trials Meyle summons. Within legal channels that are dependent on binary opposition, the accuser must adopt the position of having been wounded in some way by the accused; they must be steadfast that the accused has transgressed a spatial or behavioural boundary.

The conceit of these legal proceedings relies upon a shared understanding between accuser and the court that these creatures belong to an order of being in which humans, on behalf of God himself, hold dominion over the earth and all within it. But every so often, in the trials Evans records, there’s a break in the armour of this fiction. Without the linguistic means to defend themselves, accused animals were some- times appointed humans to act as counsel on their behalf. One of the sections Meyle excerpts features an unnamed lawyer offering an impassioned, and legally complex, defence of locusts. The lawyer argues that the trial is void as the locusts have no capacity to reason, or to act in malice. The lawyer goes on to say, that these locusts were “only exercising an innate right conferred upon them at their creation, when God expressly gave them ‘every green herb for meat,’ a right which cannot be curtailed or abrogated, simply because it may be offensive to man.”10

It’s posturing, perhaps – a performance enacted for legal theatre – but could following this unnamed lawyer’s example make room for a less antagonistic relationship with the earthly creatures around us? It might allow us to see ourselves amongst things that have no concept of property boundaries, or the market value of crops and livestock. Or perhaps, following Le Guin once more, to see ourselves as appearing as “particularly lively, intense, aware nodes of relation in an infinite network of connections, simple or complicated, direct or hidden, strong or delicate, temporary or very long-lasting. A web of connections, infinite but locally fragile, with and among everything – all beings – including what we generally class as things.”11

Scattered throughout Meyle’s installation are pewter casts made from bread and a wedge of cheese that she left outside to be pecked by birds. These holey foodstuffs offer a different way of viewing what we see, excerpts of material chosen without regard to courtroom dramas and human rhythms of toil, rest and play. If we are to read the imagined space as a study, the birds have breached its sanctity, and brought with them a way of seeing, and being, in the world differently.

Madison Kelly Tohu! Karaka! Braid! 2023. Glass, water, wood. Courtesy of the artist

Madison Kelly Tohu! Karaka! Braid! 2023. Glass, water, wood. Courtesy of the artist

Which leads me to ask: if we were to ask the birds, what might they say? Tohu! Karaka! Braid! (2023) by Madison Kelly (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Pākehā) offers not so much answers, as a way to think and feel with birds. Kelly’s practice considers sonic relations between species. The protagonists here are kakī, a taoka species endemic to Aotearoa, who make their homes in the braided rivers and wetlands of Te Manahuna Mackenzie Basin. These manu have been severely endangered for generations – in large part due to the loss of their wetland habitats and predation by introduced mammals.12 For several years, Kelly has engaged with the Kakī Recovery Programme, based near Twizel and run by the Department of Conservation, which rears kakī in captivity for the first three to nine months of their lives. Raised without exposure to predators, the young birds must learn to identify danger through artificial means, so they are played recordings of distress calls to accustom them to the sounds of warning before they reach the wild.

Upon release, the calls of the young kakī are met with the joyous replies of older birds – those raised and released in previous years – attuned to those voices through the same means. For the younger birds, these sounds are familiar, yet made anew. A call heard in real-time for the first time in their young lives. Kelly describes this call and response as a karaka, which establishes relationships, points of connection within an ever-expanding network, and sets forth a path upon which to proceed.13

In the Gallery, Tohu! Karaka! Braid!, also acts as a kind of karaka. Positioned near the entrance of the exhibition, the call of the kakī – here summoned within a soundscape composed by the artist – spills out into the surrounding architecture and ushers us in. Beneath the speakers from which the call emerges sits a percussive instrument composed of glass vessels of water. As audience members, we’re invited to accompany the manu in their song. Accompaniment requires attentiveness, micro-adjustments to rhythm, tone and volume, so as to keep pace, avoid drowning out, or straying too far from what’s offered. In Kelly’s work, the manu set the pace, laying down parameters for a response, and it’s up to us to find a way to play along.