Identities of Journey and Return

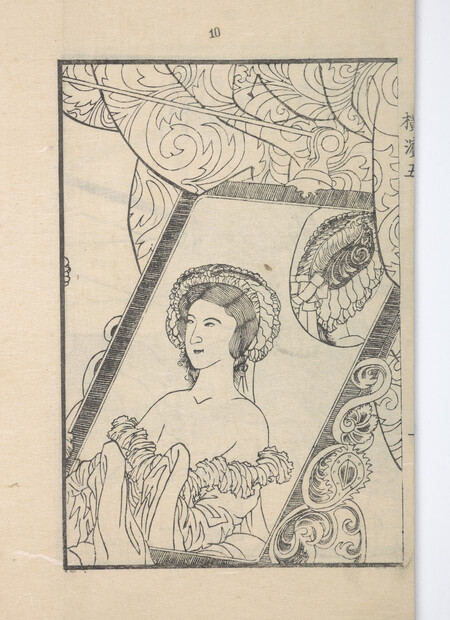

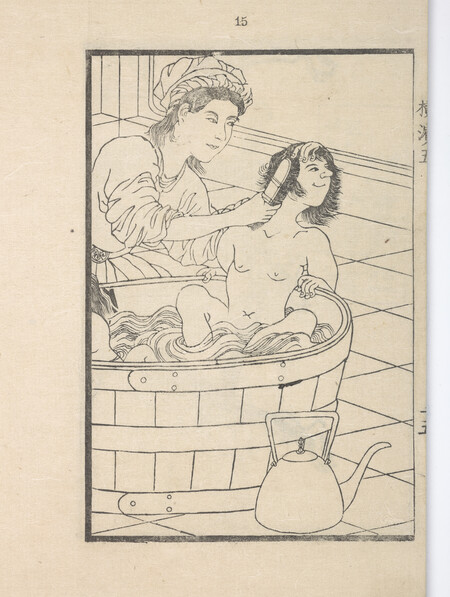

Utagawa Sadahide Yokohama kaiko kenbun-shi / Things seen and heard at the Yokohama Open Port (detail) 1865. Collection of Te Papa Tongarewa, purchased 2016

It was the novelty of seeing white people rendered by a Japanese artist that tickled me when I first saw Utagawa Sadahide’s woodblock prints of foreigners in Yokohama in the 1860s.1 There’s something slightly clumsy about the Westerners’ exaggerated noses and the forced rounding of their eyes. You can sense, in these images, the artist’s struggle to detach himself from the conventions of Japanese art and beauty; his lines waver here, unlike his assertive depictions of long, flat Japanese faces in earlier prints.

Utagawa Sadahide Yokohama kaiko kenbun-shi / Things seen and heard at the Yokohama Open Port 1865. Collection of Te Papa Tongarewa, purchased 2016

In Sadahide’s time, foreigners were flowing into the port of Yokohama following a series of international treaties – the beginning of the end for Japan’s isolationist period. Access to wider Japan was limited for these new arrivals, so Yokohama was dense with multiculturalism. Rugby, for instance, was being played there in the 1860s, whereas New Zealand’s first rugby match wasn’t played until 1870. Sadahide recorded this time of change in his bound volume of prints, Yokohama kaiko kenbun-shi /Things Seen and Heard at the Yokohama Open Port (1865).2 Its scenes document, through Japanese eyes, the unfamiliar habits and domestic details of Yokohama’s American and European inhabitants, such as chaotic bathtimes and flouncy dresses.3

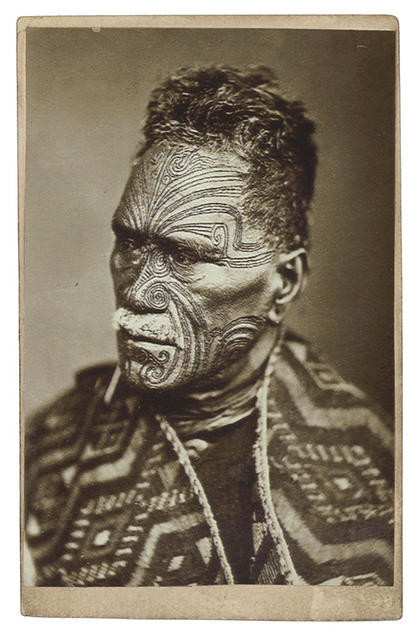

In Aotearoa, we’re more used to casting a critical eye over early European depictions of Māori by artists such as Sydney Parkinson. We look at images like The Head of a New Zealander from 1773 and scoff at the unlikely aquiline nose. Seeing these details as a fanciful ‘Europeanisation’ of the reality that Parkinson would have encountered, we have come to interpret such images as artists exerting a kind of depictive power over Māori on behalf of a much larger colonial machine. In his 1984 PhD thesis, Leonard Bell described this as “fashioning ‘realities’” for Māori “primarily geared to European tastes, beliefs, requirements and interests.”4

It’s in this context that the switched roles of European Artist and Ethnic Other, as represented by Sadahide, struck me as a delicious counterpoint to the norm. Images like his complicate our crude understanding of the direction in which power flows, and has flowed, between artist and subject, European and Other. Having been steeped in an art-historical worldview where non-Western “art of encounter” is rarely seen or spoken about, these images appealed to me as a sign we’ve shortchanged ourselves by limiting our understanding of who wielded artistic agency in these encounters.5

I included Sadahide’s prints in a small exhibition I curated at Te Papa in 2018, Things Seen and Heard, He mea kite, he mea rongo.6 The exhibition featured five artworks that represented connections between Asia and Aotearoa: ranging from Orientalist appetites among New Zealand collectors to the circuitous paths that artists have arrived here by or departed from here to. Alongside Sadahide’s prints, the exhibition included a miniature Chinese garden carved from cork, which once belonged to artist Theo Schoon (a Dutch New Zealander by way of Indonesia), and photographs by the Japanese New Zealand photographer Haruhiko Sameshima.

I brought these artworks together as access points into a history of connected and curious artists and collectors – part, I suppose, of an ongoing project to firm up a future for Asian New Zealanders by illustrating that we have a past. The Maui Dynasty, a 2009 exhibition curated by Anna-Marie White for the Suter Art Gallery in Nelson has been influential for me in this project. Its alignment of Asian, Pacific and Māori artists to challenge “our dogged cultural allegiance to Europe” opened up the power of propositional thinking as a means of subverting status quo narratives of national identity and belonging.

Unknown maker Miniature Chinese Garden 20th century. Wood, cork, plate glass, lacquer. Collection of Te Papa Tongarewa, purchased with New Zealand Lottery Grants Board funds, 2001

One revelatory fact from The Maui Dynasty catalogue has stuck with me: “In early Australasia consumption of Chinese tea was about six times as high as in Britain… This data suggest that the colonial engagement with Asia did not simply replicate metropolitan patterns but developed its own quality and intensity.”7 To me this is a thrilling claim, with implications about taste and trade that rattle straightforward ideas about our cultural lineage. Such connections may be forgotten, complicated or even vulnerable to wishful interpretation, but they also provide hopeful glimmers of alternative histories yet to be reclaimed.

One object in Things Seen and Heard that was dense with connections was Theo Schoon’s miniature Chinese garden. It could be considered just one of the ‘folk art’ trophies Schoon collected as part of his fascination with the art of other cultures. But it reminded me of a similar cork garden that sits in a corner of my grandparents’ dining room in Dunedin – theirs so big that the thought of them going to the effort to transport it to New Zealand is quite absurd. Refined over millennia, the Chinese garden is an idealised form that represents the distillation of many cultural and philosophical principles. The idea of my grandparents bringing a carved garden enshrined in glass to sit in the heart of their home (so far from where they were born) struck me as a poignant gesture – what did they hope it would remind them of as they went about their lives here?

Surprisingly, the art of cork carving is not as ancient and essentially Chinese as one might guess. Considered one of the “three treasures of Fuzhou”, cork carving is – like Sadahide’s prints – an art of encounter. Originating in Xiyuan village in Fuzhou in China’s Fujian province, cork carving is thought to have begun in 1914, inspired by painted wooden relief pictures brought to Fujian from Germany. Not only that, but much of the cork bark used for this new artform was likely sourced from Europe, where cork oaks are more prolific. The development of cork carving is a story of artistic adoption and adaption, and global trade.

At its height in the 1970s and 1980s, cork carving was an industry that employed thousands, and these cork pictures were exported for sale around the world. We might guess that Theo Schoon acquired his in Indonesia, while my grandparents might have bought theirs during a visit to Hong Kong. There’s also evidence that they were sold in Japan. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2015 exhibition China Through the Looking Glass included a hat designed by Philip Treacy for Alexander McQueen (Chinese Garden, 2005), for which Treacy “cannibalized the decorative shadowboxes of intricately cut-worked cork” purchased in Japan.8

Haruhiko Sameshima Athenes 1992. Gelatin silver print. Collection of Te Papa Tongarewa, purchased with New Zealand Lottery Grants Board funds, 2001

Utagawa Sadahide Yokohama kaiko kenbun-shi / Things seen and heard at the Yokohama Open Port 1865. Collection of Te Papa Tongarewa, purchased 2016

We might describe these artworks as a kind of evidence, but not in the conventional sense that we trust their observance of particular details like plants or geographical features encountered during a journey. Instead they remind us that there have been sophisticated minds at work on both sides of history’s encounters. Sadahide’s prints, the cork carving and Sameshima’s photographs are all products of encounter and exchange, assimilation and mutual adaption, and artistic mobility.

In Things Seen and Heard, Sameshima’s black and white photographs represented a contemporary identity of journey and return. His two photographs capture museum displays in oblique ways, presenting shadow views of display cases and their contents – one at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, and another at a museum in Greece.

Athenes (1992), for me, is a particularly rich image. It was taken by Sameshima shortly after he graduated from Elam, as he travelled Europe on a short OE. The photograph shows the shadow of a display case that holds an ancient bronze figure – the effect is that the image both conveys an intimate view and echoes with deep cultural and philosophical resonances. The elusiveness of Sameshima’s cultural lens – as the photographer framing this view – fascinates me. The idea of the artist abroad has most often implied a Pākehā way of seeing – whether it’s Frances Hodgkins or Gavin Hipkins – so what are we to make of the outlook of the Japanese New Zealand photographer in Europe on his OE?

Born in Japan, Sameshima moved to New Zealand with his family when he was a teenager. To some extent, his cultural identity evades the established frames of New Zealand art history – something I’ve suggested was also true of the Chinese New Zealand artist Guy Ngan.9 Things Seen and Heard championed these complex ways of being, showing that artistic mobility is not just the privilege of Pākehā artists.10 But the exhibition also explored the remarkable mobility of images and artworks themselves – it is after all, quite something, that Utagawa Sadahide’s prints or Theo Schoon’s garden came to be in Aotearoa, so far from where they were made.

In his own photobook Bold Centuries, Haruhiko Sameshima collates touristic representations of Aotearoa – postcards and pamphlets – and his own photographs of the country, showing himself to be a collector of images as much as he is a producer. He writes in the book’s preface of how his father returned to Japan from his first trip to New Zealand in the 1960s with photographs he’d taken and a picture book, which Sameshima writes of as the “first visual impression of this country that would become my home.”11 Something of this sentiment runs throughout Things Seen and Heard. Our memories or anticipations of places are always partly imagined, and even our memories of places we know well lose fidelity when we’re away from them. But as Sameshima writes, there is both “hopelessness and freedom” in our inability to define reality.

The miniature Chinese garden in my grandparents’ home represents a vague set of ideals rather than any real location – as records, images and objects can be just as unreliable as our memories. But their power lies in their ability to remind us not of how things actually looked, but of the sophistication of our human experiences. Through them we connect to the spirit of the artist making sense of the world changing around them, the collector’s interest in bringing distant objects closer, and of the feeling of journeying and returning – becoming a person transformed by encounter along the way.