This exhibition is now closed

Fourteen artists with connections to the Mainland are represented in an exhibition that explores the dark underbelly of the region's genteel appearance.

A Canterbury Gothic

Curator Felicity Milburn provides her view on the sinister exhibition of 14 of Canterbury's leading established artists, exploring dark themes of black humour and grim intent in the region's art.

Moider, mayhem and muffins

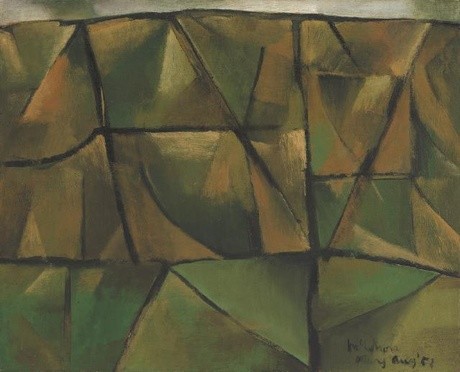

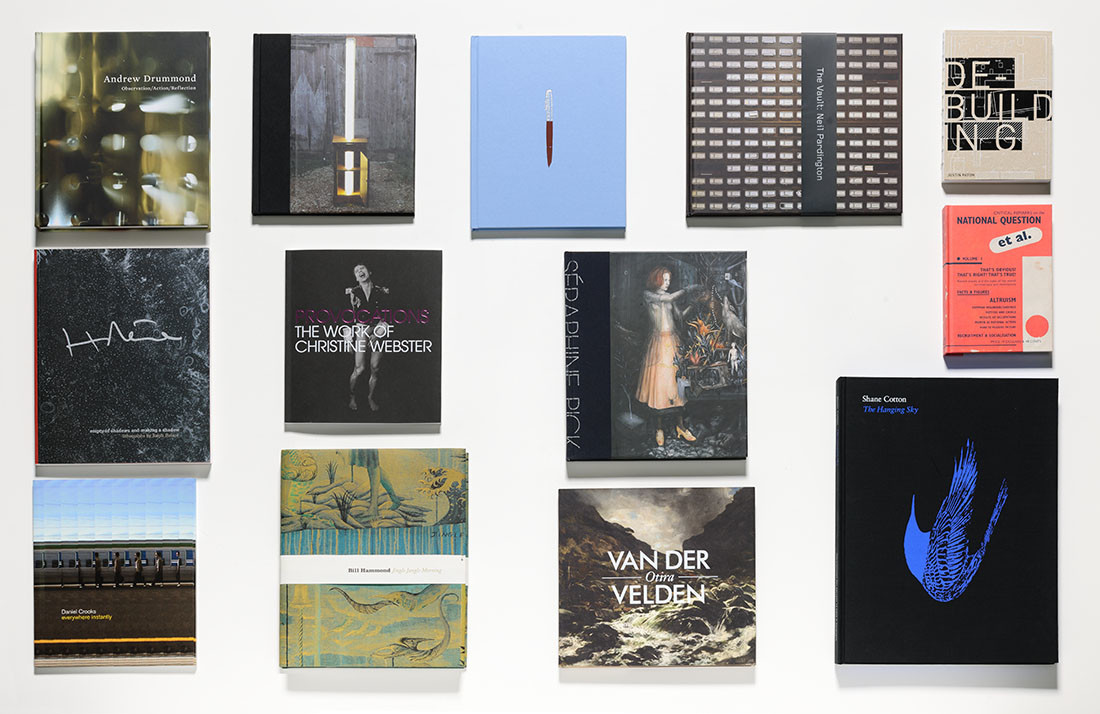

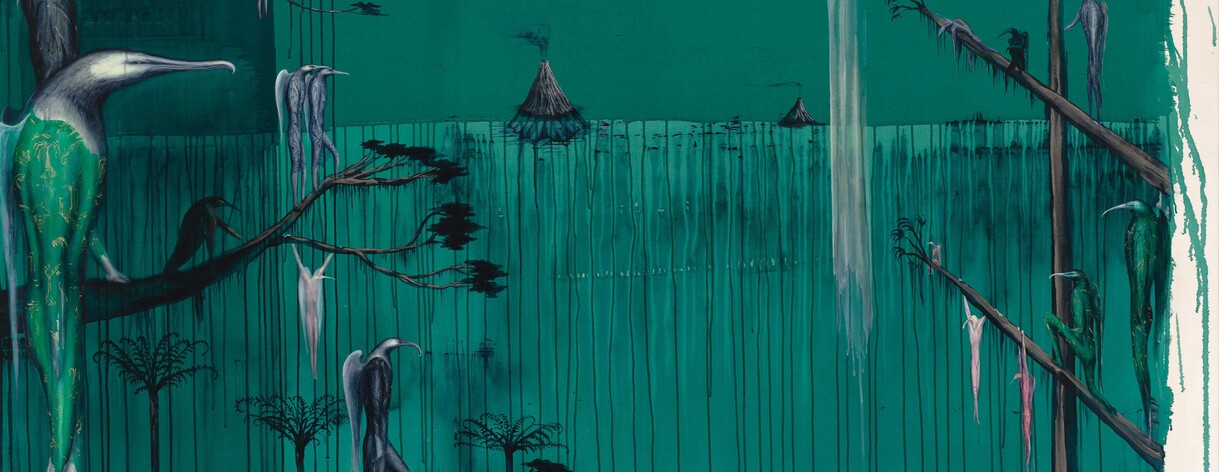

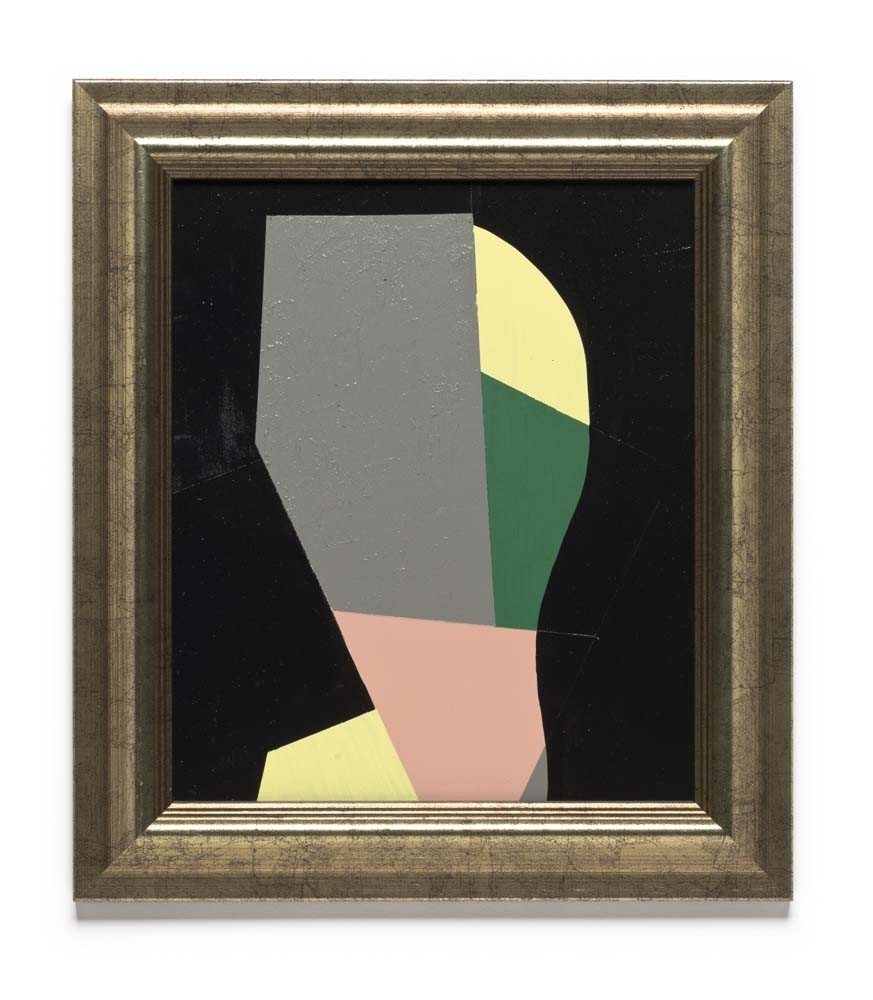

Lurking behind the South Island's legendary picture-postcard views and the stoic jaw of the Southern Man is a dark side – a gothic underbelly of paranoia, alienation, and unease. This quality, evident in the work of some of New Zealand's most talented artists and writers, is explored in a new exhibition, inspired by and named after one of Owen Marshall's most sinister short stories. Coming Home in the Dark taps the shadowy vein running through the work of 14 artists with a connection to the Mainland: Leo Bensemann, Barry Cleavin, Bing Dawe, Margaret Dawson, Tony de Lautour, Tony Fomison, Jason Greig, Bill Hammond, Colin McCahon, Trevor Moffitt, Bruce Russell, Ann Shelton, Ronnie van Hout and Dean Venrooy.

Though the selected works are born of the shadows, this is not a showcase for vampires, fake blood or monsters – unless they are the kind we find living next door (see Ann Shelton's homage to the infamous Parker-Hulme murder site in Victoria Park). Instead, the exhibition concentrates on the subtler undercurrent of isolation and anxiety that clings to the flipside of Christchurch's genteel English appearance – a seldom-advertised aspect of local life that has seeped quietly into the province's music, literature and film-making as well as its visual arts practice.

Set in the remote, spectacularly beautiful MacKenzie Country, Owen Marshall's short story relies for its sense of numbing horror not on the sudden, gratuitous killings of innocents it depicts, but on a series of related incongruities. The setting (a family outing), the philosophical musings of the chilling killer Mandrake, the loving detail with which Marshall picks out the landscape, all combine to create an environment in which the ensuing violence is not only unexpected, but impossibly fantastic. Out of a clear blue sky, still ringing with the call of birds, evil comes, unimaginable and irrevocable.

Though other regions in New Zealand have had their share of violent crimes, such events have always sat uncomfortably against Christchurch's air of respectable decorum. Perhaps perching on the neatly groomed edge of the Mainland has obligated a show of propriety, as though any admission of deviancy would be an invitation to the godless high country to swallow us up. Whatever the reason, Christchurch's almost compulsive need to sweep it under the carpet and keep it in the family has added to the frisson when, occasionally, the halo has slipped. Prejudice, violent abuse, and especially murder attain a special impact when considered against our quaintly English façade; so that in some cases, even after all those years have passed, we are still asking - can it really have happened... here?

Fitting, then, that the exhibition scene opens with a murder or, better still, a 'moider' – the seemingly inexplicable crime that scandalised the good people of Christchurch and provided Peter Jackson with ample fodder for his fairytale thriller Heavenly Creatures. The brick-in-a-stocking slaying of Honora Parker by her daughter, Pauline, and Pauline's best friend, Juliet Hulme, had something for everyone: a brutal attack, diaries filled with dark fantasy, the suspicion of a friendship between young girls that was closer than polite society allowed, and all this in a town that modestly prided itself on being 'more English than England'. In reports of the case, at the time and since, it is apparent that the location – in the Port Hills of the prim Garden City – added immensely to its shock value and newsworthiness. A chapter on the murder in Famous Australasian Crimes was entitled 'Death in a Cathedral City' and began, improbably, 'Christchurch is as English as a muffin'. (1)

Such is the soundtrack to Ann Shelton's stealthy 2001 photographic diptych Doublet {After Heavenly Creatures}, which depicts the infamous Victoria Park path in two mirror images. It is as though the paths, leading away from one another, out of frame, represent the increasing separation of history and myth, an interpretation reinforced by Shelton's later description of its subject as the site of ‘the Heavenly Creatures crime'. (2)

Of course, when Juliet Hulme and Pauline Parker were making their plans on the lush green lawn of Juliet's Ilam home in 1954, another violent episode was already part of Mainland legend. The actions of West Coast farmer Stanley Graham, New Zealand's first mass-murderer, had sent the nation reeling in 1941. Against the backdrop of the war in Europe, Graham's descent into murderous obsession ranks as one of the darkest tales in the region's history. Deep in debt and pursued by mortgage agents, Graham's increasingly abusive behaviour and fading grip on reality grew worse when the Dairy Board refused to accept milk from his farm, labelling it unhygienic. Graham claimed his neighbours were poisoning his livestock and began to threaten those who passed his house. When local constable Ted Best visited to collect Graham's .303 rifle to aid in the war effort, he first claimed it was missing, then promised to send it later. He failed to do so over the next few months and when Constable Best returned with three colleagues to confiscate it, Graham gunned them down and escaped into the bush. Thirteen days later, after one of the greatest manhunts in New Zealand's history and with seven dead, Graham was shot by police, later dying in hospital. His remarkable story was captured in a series of vignette paintings in the mid 1980s by Trevor Moffitt, who had also depicted the life of the legendary sheep rustler, James MacKenzie, after whom the MacKenzie country is named. Moffitt occupies a unique role as a painter who has consistently told the stories of regional history, often focussing on the less than heroic – villains, murders, thieves and illicit Southland moon-shiners. 'It is important that memories be brought forth and recorded and exhibited and remembered,' he has said, 'so that they become part of our image of ourselves, part of our understanding of who we are and where we came from.' (3)

In Moffitt's Eating a Raw Egg, the first reaction is one of revulsion, not at the murderous acts ahead and behind, but at the nauseatingly orange egg yolk cracked open at Graham's waiting mouth. Only at a second glance do the pressing in of the surrounding bush, the bandolier of shotgun shells across Graham's shoulder and the blood that floods his right armpit become obvious. Even then, the scene has an element of farce: Graham's mid-rampage snack is incongruous and faintly absurd. Moffitt's eye for the humorous potential in the most macabre detail – irreverent, self-deprecating and full of insight into human nature - is finely trained. Humour is a recurring element throughout Coming Home in the Dark, from the steely wit of Barry Cleavin's Reischek etchings to the taxidermy parlour games of Bill Hammond and the gallows humour of Bing Dawe.

(1) Gurr, Thomas and Cox, H. H., London, Muller, c. 1957.

(2) Ann Shelton, Public Places, Rim Publishing, Auckland, 2003, p. 7.

(3) Trevor Moffitt, quoted in ‘The Hokonui Moonshine Series' by Adrienne Rewi, Eastern Southland Gallery, Gore, 1998, p. 18.

Related events

Montana Wednesday Evenings

Reading and Discussion: Wednesday 20 October 6.00pm

Award-winning New Zealand writer Owen Marshall reads and discusses extracts from his works. Venue: Philip Carter Family Auditorium, ground floor.

Film

Wednesday 27 October 6.00pm

A fascination with the darker side of life in our rural community is explored in the New Zealand film Vigil, produced by Vincent Ward in 1984. Venue: Philip Carter Family Auditorium, ground floor.

-

Date:

15 October 2004 – 27 March 2005 -

Curator:

Peter Vangioni, Felicity Milburn -

Exhibition number:

726