Glen Hayward Yertle 2011. Acrylic paint, metal, wood (kauri, pine, puriri, rimu, totara). Courtesy of the artist and Starkwhite, Auckland

Gazumped

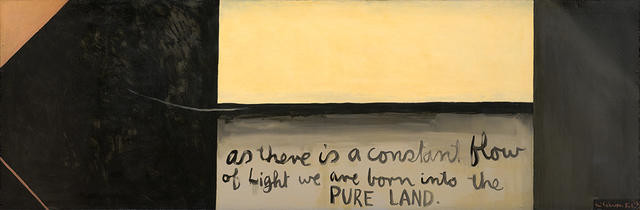

One of the exhibitions brought to a halt by the 22 February earthquake was De-Building, which critic Warren Feeney had described only days earlier as 'Christchurch Art Gallery's finest group show since it opened in 2003'. Seven months on, the show's curator, Justin Paton, reflects on random destruction, strange echoes, critical distance, and the 'gazumping of art by life'.

There's a lot you're up against as a curator in New Zealand when organising an international group exhibition. You're up against distance and budget-breaking freight costs. You're up against the suspiciousness of overseas galleries, who at their most officious seem to doubt that we in New Zealand have running water or a clue in our heads. You're up against time differences, exchange rates, and the whims and wants of collectors. But what I never expected to come up against was a natural disaster.

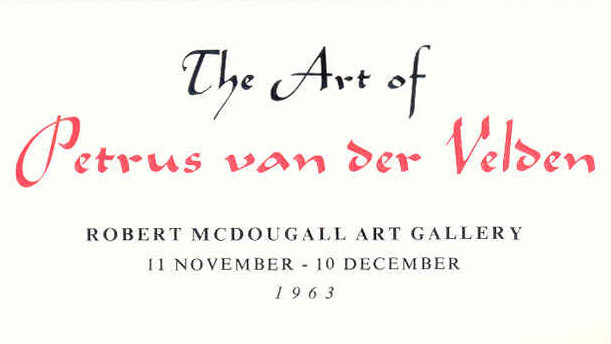

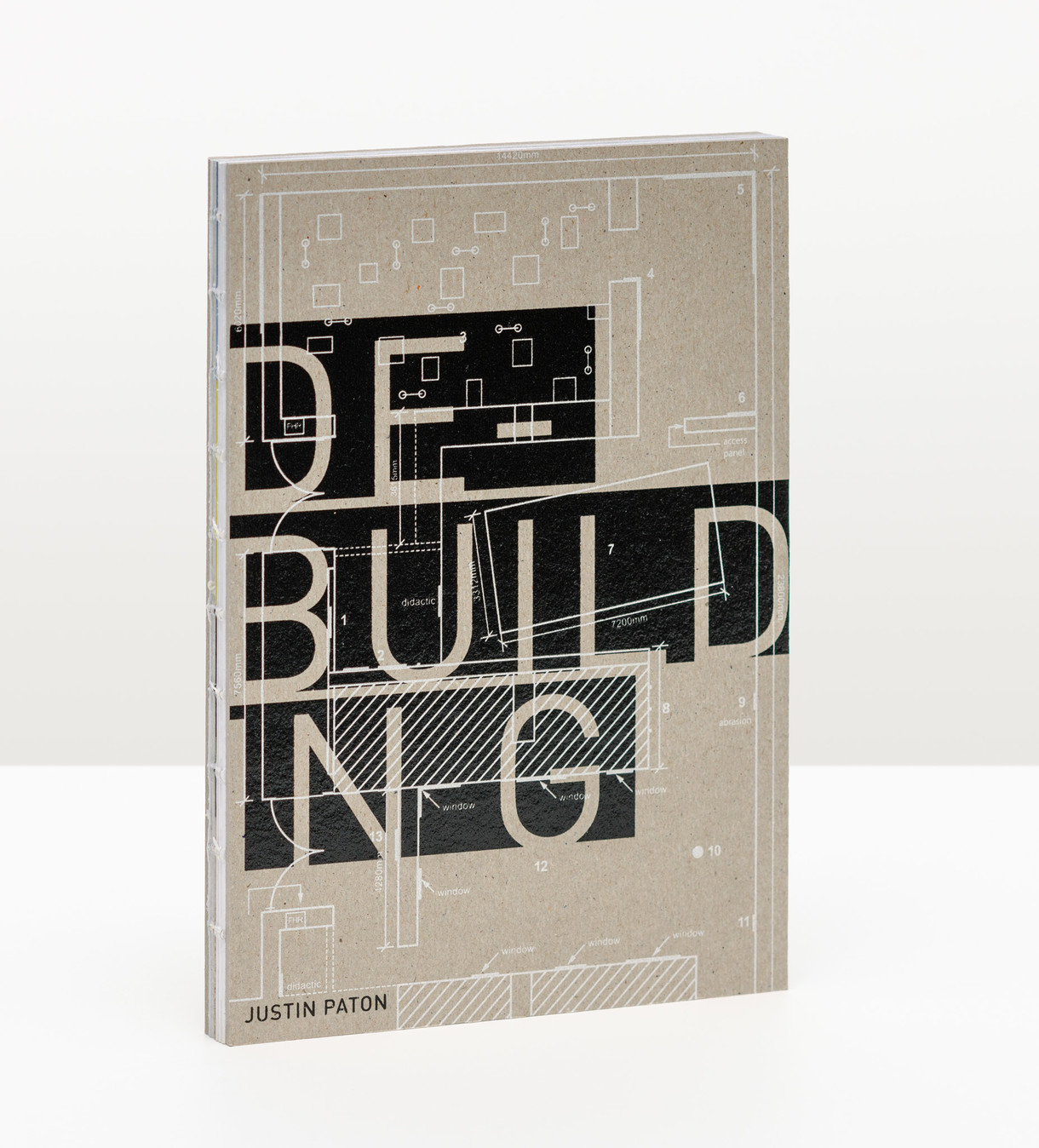

Obviously, I'm not the only curator in this building, or this city, to have had an exhibition undone by the earthquake. But I think I can claim some special status, some kind of he-never-saw-that-coming prize, in that my exhibition was actually about architecture and its undoing. As visitors to the Gallery and Bulletin readers will know, the exhibition De-Building focused on a moment that public galleries usually hide from their audiences – the moment when an exhibition ends, the doors close and the 'de-build' begins. I've always been fascinated by this rowdy, in-between period, when crates are wheeled in, walls broken down or sanded and painted, and all manner of strange new views open up.

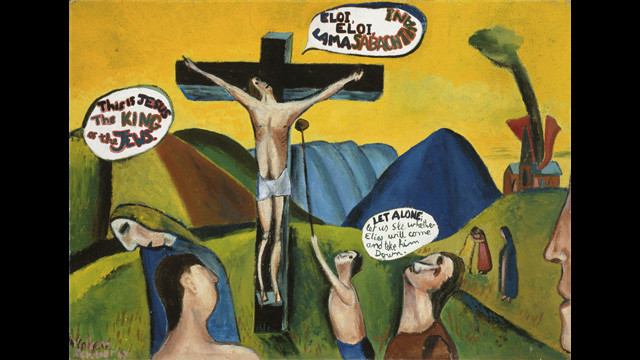

De-Building brought together fourteen artists who share this kind of aggressive curiosity about the spaces they show in – from Liz Larner wrapping a corner of the Gallery with a fierce network of high-tension chain to Pierre Huyghe sanding back white paint to reveal the strata of colour beneath; from Monica Bonvicini slowly hammering her way through a white wall to Peter Robinson supersizing the props and support systems that usually protect art. 'For all fourteen artists', I wrote in a preview for this magazine, 'the "de-build" is a moment of possibility and potential – a moment when energy is high, categories get confused and art bumps into non-art.' Just how hard those two things would bump into each other, I never anticipated.

Security camera footage showing Peter Robinson's Cache during the 22 February earthquake

You know the story by now. How a magnitude 7.1 earthquake shook Christchurch awake at 4.35am on 4 September, causing chaos across the city but, incredibly, no loss of life. Inside the Gallery very little art was damaged, but nothing was normal. While our exhibition teams worked across the ensuing week to clear several exhibitions from our spaces, among them the hair-raisingly fragile Andrew Drummond show, Civil Defence teams worked in adjacent spaces to get the city running again and media milled about in the foyer and forecourt. The building and the galleries were soon open to the public again, but it was strange to re-experience the collection in the wake of the quake. Though physical damage was scarce, almost every work in the building seemed subtly changed in character. Petrus van der Velden's Mountain stream, Otira Gorge felt less like a spiritual vision than a seismic one – a front-row report from the Alpine Fault. John Reynolds's 1,654-piece installation Table of dynasties became a kind of in-house quake monitor – a miniature skyline of stacked canvases that collapsed whenever an aftershock exceeded 4.5. And plenty of people, encountering Ron Mueck's sculptures of pensive and vulnerable figures, saw the image of their own worries. 'That was me', one visitor said as she looked at In bed, Mueck's sculpture of a colossal woman staring at some unnamed anxiety, 'at 5.30am on the 4th.'

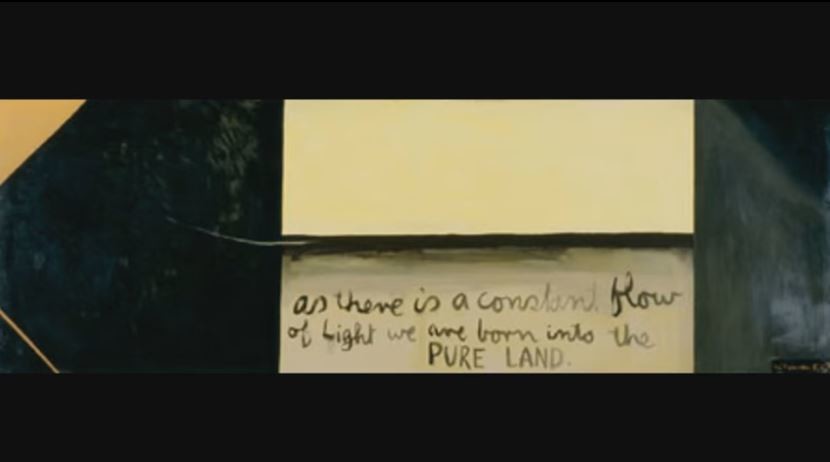

My own worries at this time were of the luxury variety. I was anxious about De-Building. 'Is such a show still thinkable?' a colleague from Wellington asked me by email. And although I gave her a no-two-ways-about-it reply, the truth is that I was nervous. Though the show was still months off, I feared I was about to commit an act of vast tactlessness – the equivalent of launching your big show about icebergs shortly after the Titanic went down. Of course, as a curator of contemporary art, one wants to be committed and unswayed. But one doesn't want to be a dick. Nothing could be more tedious than a curator going on about how important it is for art to be unsettling when his audience consists of people who are actually unsettled. But five months is a long time in art. By the time the opening date for De-Building rolled around, the aftershocks had died right down, and the Gallery was on an extraordinary roll, with the Ron Mueck exhibition receiving more than 130,000 visitors by the end of its run, many of them first-time visitors. As well as offering those viewers a sculpturally vigorous follow-up to Mueck, De-Building arrived amidst furious local debate about demolition and preservation, and this, I felt, gave the show a relevance – a usefulness – that it might not have had previously. Every time you moved through the city there was some new hole in the urban fabric, and the city's planners and preservers were in full and frantic voice. Against this backdrop, several works in De-Building seemed to sing out with new urgency. Watching three films of American 'anarchitect' Gordon Matta-Clark reshaping disused buildings, I dreamed of seeing some Christchurch maverick rescue a few supposedly 'useless' buildings for even brief imaginative use. Susan Collis's screws – eye-fooling replicas exquisitely fashioned from precious metals – looked startlingly topical, given the newly elevated status of builders and engineers in Christchurch. And Fiona Connor's installation of nine facsimile windows What you bring with you to work, which was created in Melbourne in early 2010 and purchased by the Gallery shortly after, suddenly felt like a customised reflection on the lost walls and windows of Christchurch. Looking through Fiona's windows into the strange spaces behind our walls, you could see the dust and detritus of recent builds and de-builds alongside one particularly talked-about souvenir of the September quake – an action plan that was stuck to the wall by Civil Defence teams.

Fiona Connor What you bring with you to work (detail) 2010. Window frames, glass, timber, fittings, wax, paint, 7 windows exhibited from a group of 9. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2010

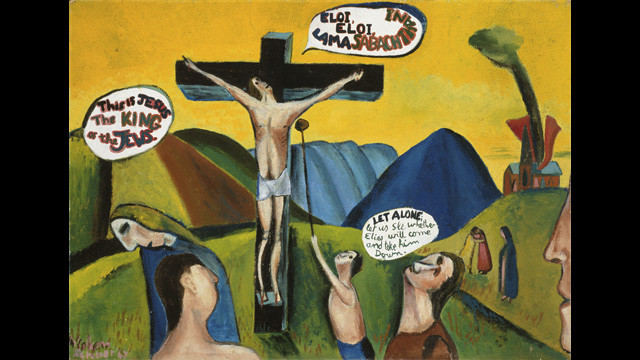

Unfortunately, the souvenir was also a premonition. Five months may be a long time in art but it's not long at all in the realms of geology. Round lunchtime on 22 February, seventeen days after De-Building opened, the room I was sitting in with ten other colleagues began to rack around violently (we were planning the next copy of the Bulletin – but let's not read anything into that). Elsewhere in the building, shelves lurched forward like drunks and spat out hundreds of books; gas bottles you'd need two people to lift fell and spun like skittles; and, in De-Building itself, Robinson's four-metre-high monoliths shook and toppled, like props in some end-of-the-world blockbuster. Measuring 6.3 on the Richter scale, the quake was later described as an aftershock, a 'natural consequence' of the September quake. But there was no comparison. Far closer to the earth's surface and to the city centre, it took 181 lives and left the inner-city looking like the kind of war-zone most of us associate with far-off places. The difference between September and February, you might say, was the difference between bent and broken.

I recall wondering briefly about the fate of De-Building as I evacuated the Gallery with colleagues. But once we reached the street, it was clear there was more to worry about. For many people, there was trouble at home. And Civil Defence were back in the building – every bit of it. It wasn't until two weeks later, when my family and I were in Sydney, that I was able to catch up properly with colleagues about the Gallery and its prospects. Would we be reopening? Would we be reopening De-Building? And if we chose not to, was it a kind of soft censorship? The question turned out to be theoretical, because this time Civil Defence were not leaving in any hurry, there were loans to be returned and the show – Robinson's installation especially – was seriously shaken up. Nonetheless, it was shocking to register how rapidly an entire exhibition – its meanings as much as its materials – could be swept up by an external event. Suddenly Santiago Sierra's video, A worker's arm passed through the ceiling of an artspace from a dwelling above, suggested security footage of a person trapped. Monica Bonvicini's work Hammering out, with its crunchy, ear-splitting soundtrack of sledgehammer strikes, felt painful rather than exhilarating to look at. Matta-Clark's films looked like live dispatches from Christchurch's hardest-hit suburbs, where the insides of many houses were suddenly open to the outside. The very layout of the show, which was tight and labrynthine, seemed sure to make viewers feel nervous. And then there was Callum Morton's massive crate, Monument #24: Goodies. With its internal battering rams and deafening feline soundtrack (Morton was thinking of the famous 'Kitten Kong' sequence from the British comedy The Goodies), it was a work designed to trigger both fright and laughter in unsuspecting viewers. After the quake, it's fair to guess that the fright factor would have trumped the laughter. It all felt too soon, too close, too topical.

Which is, it has to be said, just not fair. What we have here, in fact, is a bitter inversion of art's usual predicament. Art today longs to be topical, outward-looking, connected, responsive to site and situation. And it spends a lot of time fretting that it isn't. But an event such as the earthquake short-circuits this logic horribly. Instead of a dearth of relevance, suddenly there's a ghastly surplus of it. Like a boor at a party, the quake insists on casting its shadow over every topic, on monopolising every conversation. For anyone familiar with contemporary art, post-quake Christchurch threw up dozens of unsettling echoes: I was reminded often of Doug Aitken's extraordinary installation House, in which the artists' parents sit silently facing each other as their own family home is brought to the ground around them; and more than one person joked about the whole city becoming an et al. installation. The prize for Best Imitation of an Artwork by an Earthquake had to go to the twenty-five tonne Port Hills boulder that rolled through the roof and into the hallway of a Heathcote home, thereby mimicking, with chilling accuracy, Callum Morton's rock-in-a-shop sculpture for the 2008 SCAPE exhibition. If you've been trained in art history's method of compare and contrast, then you can't help looking for meaning in these echoes. But natural disasters don't mean in that way. They just are, and before long I grew bored with the way this disaster was appropriating perfectly good artworks for its own tedious purposes. Call it poetic injustice – the gazumping of art by life.

Callum Morton Monument #24: Goodies 2011. Wood, pneumatic machinery, soundtrack, sound equipment. Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne

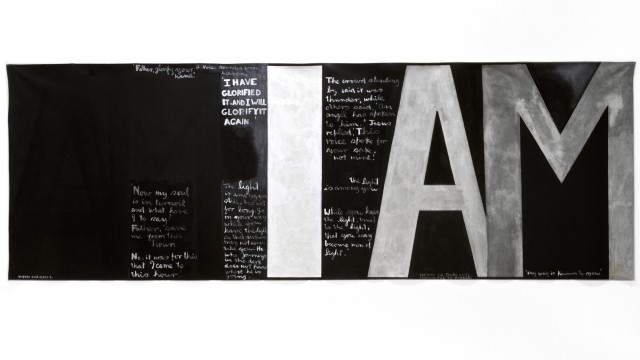

There is plenty of real reconstructing to be done in the Christchurch artworld: of galleries, studios, libraries, teaching spaces. But one of the things I also want to see reconstructed at Christchurch Art Gallery is not physical. It is, to use an odd phrase, a sense of distance – a buffer zone between art and the world. I realise this doesn't sound very sexy. In the visitation-obsessed world of the modern art museum, distance is not a quality you hear anyone praising. And distance also sounds inimical to today's socially oriented artists, who want to rub up against the world. But one of the things the quake has taught me is that a certain distance between art and the things it wishes to address is crucial. It is a critical distance, in every sense. It is what allows us to be reflective, to think our own thoughts. It is like the distance required for a metaphor to work – the imaginative gap we need to cross when someone likens one familiar thing to something very unexpected. No less than the physical objects in its collection, this distance is one of the precious things that a gallery exists to preserve. And what you realise, when art stops and Civil Defence fill up your gallery, is that it is also precarious. Just as the quake has stripped buildings back to a state of embarrassing nudity, where all their wiring and cobwebs are exposed, so it has exposed the amazingly intricate and vulnerable network of assumptions, faiths and investments that has to come together for this public space of contemplation and free thought to exist. So, in addition to the many physical repairs being made to the building, this is what we are reconstructing over the next few months: a space where art can be exactly as silly, frivolous, pissed off, unsettling, loud, wayward and playful as it wants to be.

In that spirit, there's one artwork in particular I'm looking forward to seeing. We're putting several major installations from De-Building back on show when the Gallery reopens, among them Peter Robinson's Cache and Fiona Connor's windows, which will be installed along the twenty metre sweep of the longest wall in our building. But the sculpture whose spirit feels especially galvanising right now is Glen Hayward's Yertle, his eye-fooling carving of paint-pots rising skyward in an improbable, well-nigh impossible, tower. But of course, it's not impossible, because the artist made it happen. At a time when we're all far-too-acutely aware of the tendency of human structures to teeter and collapse, Hayward's comically precarious tower feels like a welcome retort to the forces of gravity – a crucial assertion of art's ability to fool the eye, ignore the building codes, and build some wonder back into the everyday.

De-Building ran from 5 to 22 February. It was accompanied by a catalogue, which is still available from the Gallery Shop. A version of this piece was presented at City Gallery Wellington on 18 May 2011 at the 'Re-Construction' symposium organised by Adam Art Gallery and City Gallery.

![Burial in the winter on the island of Marken [The Dutch Funeral]](/media/cache/53/c1/53c1843bcceaf9c7adc72a4a5032e2b9.jpg)