The last five years

Repairs to the Gallery foundation and the forecourt. Photo: John Collie

An oral history of the Gallery building, 2010-2015.

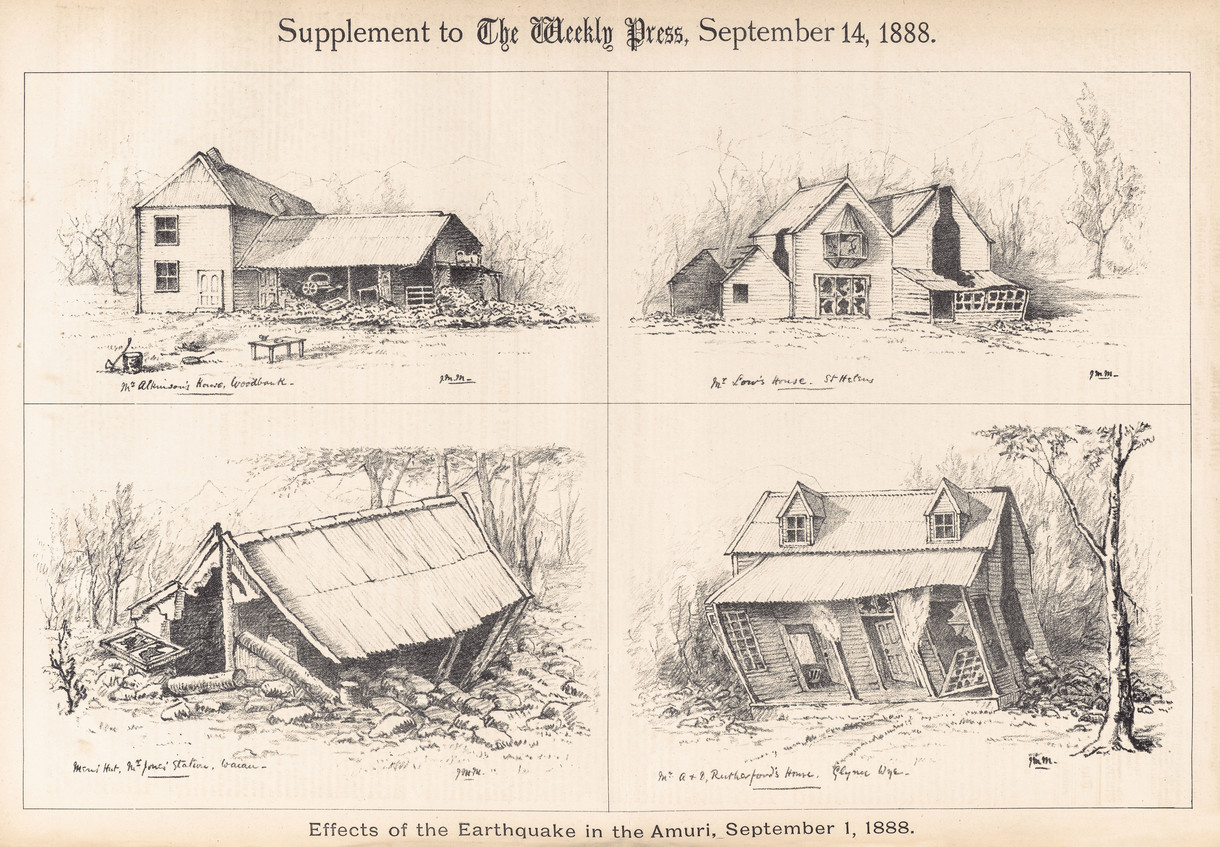

An earthquake measuring 7.1 on the Richter scale hit the Canterbury region at 4:35am on Saturday 4 September 2010.

LYNLEY McDOUGALL: I got to the Gallery about 5:30am. I came to look at the building; I was concerned about the façade because I imagined that some of it could have shattered. But when I checked everything, I saw that the building had held up and been very strong. Everything was secure and only one pane of glass was slightly cracked. Then Michael Aitken arrived, and I asked how we could help. Then the police started arriving, and all the different organisations that support Civil Defence. I had to figure out where we could put everybody.

MICHAEL AITKEN: It was my month on as the city's Civil Defence Controller. I woke up at whatever it was, 4:35am; made sure my family was still alive, threw some clothes on and drove into town. We couldn't get generators going at the council building, and then we went over to the Gallery as our back-up site. The funny thing for me was as we walked around the front there was a cleaner inside just cleaning away as if nothing had happened.

BLAIR JACKSON: Civil Defence came in relatively quickly that day and took over, but most of their occupation was just in the foyer spaces. At the time it seemed like a major occupation.

MICHAEL AITKEN: We had Bob Parker and the other mayors on the phone and they declared a Christchurch emergency. I think initially we made it for 72 hours and then we got it extended as it became quite apparent it was going to take a bit more than 72 hours to get this sorted out. Once you declare an emergency then the controller's powers are massive. You can do amazing things—which of course you very rarely have to call on. Although we didn’t know it then, actually September was remarkably well contained. We got it to a manageable state relatively quickly, and once you get it into a manageable state you really don't need the powers of declaration.

NEIL SEMPLE: When I got there the place was full of people doing Civil Defence work. I knew we had a role to play, but I don’t think I appreciated exactly what it would mean for the Gallery to be headquarters for Civil Defence in a full scale disaster. There were extraordinary powers in place for people to commandeer our spaces. We had some sensitive needs in regards to the art on the walls, and fortunately people were respectful of that, so we worked with them to enable them to do whatever they needed with our building.

BLAIR JACKSON: I felt a sense of general relief on arriving at the Gallery, and checking the spaces—relief that everyone you knew was fine, and the comfort of knowing that the building was so strong. We felt like we'd dodged a bullet. But there was a concern about what would happen next: the whole Ron Mueck show was about to arrive.

JENNY HARPER: I was staying with some people in Akaroa. It was a pretty rocky ride out there. I drove straight back and was at the Gallery practically all weekend. My main focus for the next ten days was being in touch constantly with lenders to Ron Mueck. Keeping that show on the road seemed essential—when I say keeping it on the road, part of it was already on the sea coming to Lyttelton, and I wasn't sure if ships would be able to dock there. But at the same time Christchurch itself wasn't so badly affected, and I can remember saying to colleagues I defy anyone to come from the airport into town and say that anything has happened here.

NEIL SEMPLE: We had colleagues contacting us from international galleries, asking how we were affected and whether or not they should be sending their works and their couriers—you know, they could be sending people into a disaster zone.

BLAIR JACKSON: Jenny did a lot of work to reassure the lenders and organisers of Ron Mueck that it was a good idea to bring it here. The disaster was over; we'd been through the worst.

NEIL SEMPLE: We reopened ten days later—and it seemed like a very long time to have been closed. Ron Mueck and his assistant came out, and we all had a great time installing the show. Christchurch was by that point relatively normal, the bars and restaurants were open again.

JENNY HARPER: People were unsettled. There was an air of pensiveness and general concern in the community. I think this added to appreciation of the humanity of Ron Mueck's works—from Dead Dad right through to the old woman almost dead at the end of the show, through cycles of birth and strange figures in different situations. There was Woman in Bed, from the Queensland Art Gallery's collection, which is modelled on Cas, Ron's wife; and I remember one of our visitors saying ‘that felt like me, I felt like her on September 4th’. I think the community was openly receptive to the show in a way they may not have been otherwise; or perhaps the September earthquake changed the way they saw the work.

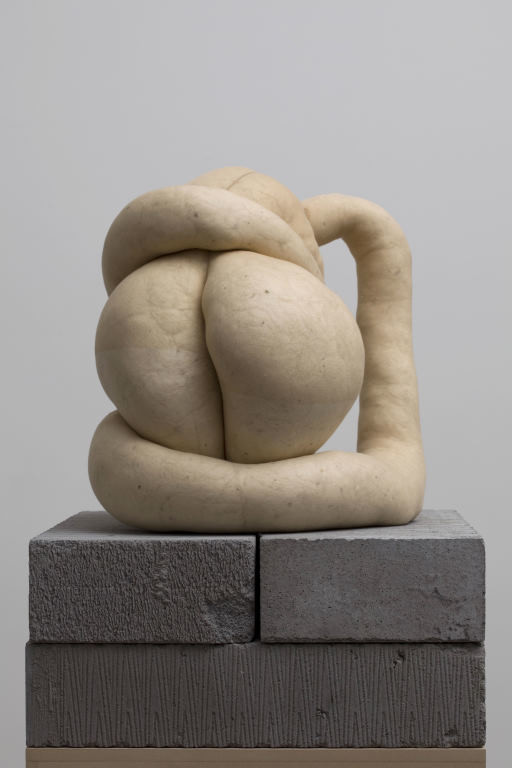

MICHAEL AITKEN: What Mueck does with scale—making you feel big or small—mirrors the incredible powerlessness of being in an earthquake. The next show, Debuilding, was also timely, but in a different way. The art gallery, I think, may be prescient; it sees ahead and prepares us for what we don’t know is coming up.

Mayor Bob Parker in the Gallery foyer. The Gallery became the Christchurch Response Centre for seven months following the February earthquake. Photo: John Collie

The glass façade, and Bob Parker's parka, became symbols of the disaster in the early days. I guess the Gallery building took over from the Cathedral in a visual sense as a symbol of Christchurch for people from elsewhere.

An earthquake measuring 6.3 on the Richter scale hit Christchurch at 12:51pm on 22 February 2011. The peak ground acceleration was twice the force of gravity. It devastated the city. 185 people were killed and many thousands were injured. A national state of emergency was declared which lasted until 30 April. Christchurch Art Gallery was again designated as the emergency response centre.

BLAIR JACKSON: In the February earthquake, several of us were in a meeting about the website. We'd started a little late, which is a good thing; if that meeting hadn't run late a lot of us would have been in the city that lunchtime.

NEIL SEMPLE: We were looking at our watches quietly lamenting the fact the meeting had gone on twenty minutes too long. And then the earthquake threw people on to the floor of the office. Screaming and swearing. After it had stopped we checked we were all OK, and then people's instincts took over and they did what they most urgently needed to do. For some people it was to find their children or their partners who might have been in town—checking on people who they cared about.

SEAN DUXFIELD: I was in the collection handling area. When the earthquake hit I remember standing there and looking at two tables thinking I should probably get under one of those, but I couldn't actually physically move. The lights were swinging and swaying, light bulbs were falling out and big heavy things were sliding backwards and forwards across the floor. I remember when it all stopped putting my hand on my heart, feeling it motoring. I was standing in front of a camera, so this footage has been played in lots of talks. I didn’t get a sense at the time that it was as strong or as violent a shake as you see when you watch the footage, because your brain takes a while to process what's going on.

LYNLEY McDOUGALL: I was in the loading bay, and a whole lot of huge gas bottles fell over and were rolling around. It was an incredible shake. My first thought was to get out and into front-of-house, so we could get the visitors out. Again, the building was quite safe. We had a couple of ceiling tiles down. The glass doors had shattered and that was very frightening, especially for the school children who were there at the time. We didn't have alarms going off and the plant room had held up well. It was actually surreally quiet afterwards. I mean, it sounds ridiculous, but I was really proud of how the building had stood up.

BLAIR JACKSON: I don't think we realised the extent of it in that meeting room. The building masked a lot of the strength of the earthquake. But then when we moved out into the Gallery spaces and heard accounts of the Provincial Chambers falling, I guess that's when it dawned on me that this was real. Lynley and Neil were both at the Gallery, and when things were under control and the public was evacuated I went into the city to find my kids who were at Unlimited at the time. I was walking against the flow of people, before the police stopped people going in. I found them and made sure they were with friends who took them home. Then I went back to the Gallery, walking past the PWC building in an adrenalin-fuelled state. Civil Defence had started to arrive and were setting up in the foyer.

MICHAEL AITKEN: I was in Wellington at an earthquake conference, just about to go and do a panel discussion about how brilliantly we'd managed September. Most of the Civil Defence people were there, as was the Police Commissioner Dave Cliff; and the head of the Fire Service and the head of ECan's Civil Defence and our Civil Defence. It was funny because all these pagers went off simultaneously around the room. The story started unfolding and we had to rapidly get as many of us possible back to Christchurch—which was a struggle. Police and Fire were helicoptered down very quickly. The rest of us ended up on a very small Air Force plane. We got back into Christchurch at about 6:30pm that day, but by then things were well underway at the Gallery.

NEIL SEMPLE: The aftershocks kept coming—once people had been evacuated I stood under a kind of lintel by the shop, waiting for the Civil Defence people to arrive. All of our automatic sliding doors had smashed and there were piles of glass that people had to step over to get into the building. The senior managers from Council who were heads of Civil Defence arrived quickly—they just walked over from the Council building. There was little more we could do. We made sure the gallery doors were locked, and Chris Pole and I went through with torches to check the condition of the works. Those things that were not going to get any worse, we left; but if something was at risk of further damage we made it safer.

JENNY HARPER: I was at Koh Samui in Thailand, and I heard about it through a text from someone at Te Papa. We watched the television all night and were aghast—but in a funny way I saw more of what had happened than if I'd been there because the power was off in Christchurch. I rang Blair. I can remember the sense of strength I got from him. He said look, there's nothing you can do; the Army is in the building and we've been taken over as a civil emergency. People are sleeping in the corridors.

BLAIR JACKSON: I got a call about midnight on the second night from the head of Civil Defence saying they needed more space and that they were organising for the Army to remove the exhibitions. He wanted my permission to tell security to unlock the doors to the exhibition galleries. I wouldn't give it. I rang and organised a group of staff that could be there early in the morning. We went in and took down as much of the van der Velden and Bensemann shows as we could physically manage.

LYNLEY McDOUGALL: I've never handled paintings before but I got a crash course in how to do it, with Sean, Neil and Blair. I put some gloves on, and they explained do it like this, never walk backwards, and so on. I felt really pleased I was able to do that and help clear out the gallery spaces so we could hand it over in a managed way.

JOHN HAMILTON: I arrived in Christchurch on the evening of Wednesday 23rd. My first port of call was the then Civil Defence group op centre at the School of Engineering out at Ilam. I came into the art gallery the following morning, by which time the Christchurch City Council Civil Defence people had established the base of the ops centre. We referred to it as the Christchurch Response Centre.

There was a huge number of engineers being briefed and prepared to go out and do structural assessments and they were milling in the foyer between the coffee shop and the stairwell and the reception desk. You had to run the gauntlet of the media to get into the building, they were outside. We deliberately excluded them from being in the building because experience shows that once the media start to climb all over the people who are trying to manage the operation, it gets disruptive. But the error of our ways was that we hadn't provided any facilities for the media lined up outside; they had no shelter. We put up tents on the concrete forecourt, but they still had to do their interviews standing outside.

NEIL SEMPLE: The Gallery was used as the backdrop for all the national media about the earthquake. The glass façade became the symbol of Christchurch through the earthquakes. People were amazed that it hadn't broken. The glass façade, and Bob Parker's parka, became symbols of the disaster in the early days. I guess the Gallery building took over from the Cathedral in a visual sense as a symbol of Christchurch for people from elsewhere.

JOHN HAMILTON: I was there as the national controller until the 30th April, responsible for coordinating and managing the whole of the national resources that were available for the response. One minister, who shall remain nameless, said gee, you're the most powerful bloke in the country; and I said I don't think so minister; the authorities are all in the legislation. I hasten to add we didn't use nearly as many of the authorities that were available. We didn’t have to, but they include requisitioning buildings, vehicles, that sort of thing. It certainly provided for cordoning off or restricting access to areas. It provided for emergency demolition of dangerous buildings, all that sort of activity which took place.

It was surreal for us to be working in the gallery—initially with masterpieces still on the walls. There we were worrying about a modern day disaster and in the background was a painting by van der Velden from the 1800s, really dark and stormy and tempestuous, of the Otira Gorge. It was a weird feeling. As the response team got bigger and bigger we expanded further into the galleries and then upstairs, including taking over Jenny Harper's office.

Emergency response staff recharge in the Gallery foyer. By this point the exhibitions had been dismantled and packed away, but the signage remained: Photo: John Collie

JENNY HARPER: At first Gerry Brownlee occupied my office, and then John Hamilton, for quite a long time. He didn't mind me popping in to pick up a book or a file, or dropping some rubbish in his bin on autopilot, and we had some good conversations.

JOHN HAMILTON: We were quite worried about an artwork in Jenny Harper's office—she assured me it was really important. We didn't have a clue what it was but that was because we were philistines. We took it off the wall and put it behind the couch to keep it safe so that it wouldn't fall off in the aftershocks. And another story about Jenny's office: one day I remember there was a ginormous aftershock and I dived under the desk with a staff member and did the drop, cover and hold. When the shaking stopped we looked up at the big glass desk and said: actually that may not have been the best idea.

MICHAEL AITKEN: I had an office upstairs, but one of the things that really struck me was the large numbers of people constantly in the foyer. The sheer volume of people in that downstairs area was absolutely amazing. It was a bit like one of the openings, you could hardly move for people. The Gallery was perfectly suited to the job because it had all these separate rooms—you could concentrate people in different areas. The building was remarkable in its ability to house something it was clearly not designed for.

LYNLEY McDOUGALL: The Civil Defence people were coming to me saying, ‘Where can we go, how can we get power?’ ‘We need more light in this area.’ ‘It's cold in this room.’ Over the months they were there, my building manager Brad and I continued to sort out those housing issues for them. Things went into their natural places; they brought in massive bain-maries and the café was used to cater for hundreds of people.

JOHN HAMILTON: Coming from a military background I knew the value of this: the endless stream of good coffee and food that came out of the café at the Worcester Street end was a huge morale booster for the people who were working in the Gallery. In fact it became a bit of a hub because we found there were all sorts of officials from various parts of Christchurch who were making excuses to come into the Gallery ostensibly to meet someone, but so they could have a good cup of coffee and a hot meal.

NEIL SEMPLE: It was difficult to get into the Gallery as the red zone cordon had gone up. There was Army on the checkpoints, New Zealand police, Australian police sometimes; and coming from home I had to go through three checkpoints to get to the Gallery. In the early days I found that wearing my fluoro bike jacket made me look like I was some kind of official, and that and my Gallery ID got me through the various zones.

DONNA ROBERTSON: You had to have a pass to get through the checkpoints, and they were always moving. I think I borrowed a hi-vis polar fleece off my partner's brother, so I felt totally good—warm and official. I arrived at the Gallery on the Thursday to help with web and social media. There were so many people there—a massive influx of hi-vis. Our job was to put information out there, via the council website and Facebook and Twitter: spreading information and correcting misinformation, especially early on when there were a lot of rumours. We were tracking other media so that we could give the correct info. Actually, it was a great distraction from being maudlin or dwelling on things. You felt that you were useful, even if a lot of the stuff we dealt with was negative. It was satisfying to be able to give people some clarity. Not everyone had power or the internet but they could get information from people around them who did.

There were a lot of aftershocks in that period, and the building would make funny noises like a big ship creaking, like it was OK with what was happening. I found it almost comforting—and it was good to be somewhere I was familiar with, even if in a totally different context. There were people from all over the library seconded to different jobs—we were all a big gang really.

BLAIR JACKSON: It was quite comfortable sharing the building. And I was in my own workplace, able to carry on—there was a sense of order and continuity there. If the Gallery hadn't been the Civil Defence headquarters, it would have been much more difficult for us to have had access to it. Actually looking back, and it's a really weird thing to say, but I almost enjoyed the experience. I would never want to do it again but it was exciting.

DONNA ROBERTSON: One day I was upstairs in a room that had really interesting photos in it, checking the status of a building for an owner. There was an absolute belter of an aftershock and I said to Warwick Isaacs, that'll be a 4.1 because it feels like a 4.2 but I'm always one point out. Afterwards he came and saw me and said I was right. There was a feeling of camaraderie. Of black humour. We were all in it together.

JENNY HARPER: We learned—as you do in many crisis situations—that you're not an isolated individual. You are part of a community and your neighbours' problems are your own. When the Gallery Apartments next door needed to be demolished, that became quite a significant thing for us.

BLAIR JACKSON: We had to move the collection. Because the crane that was going to take down the apartment block would swing over the collection stores, we thought it best to remove it. And Civil Defence and Council moved out, primarily because they couldn't have their staff there while the building next door was demolished. So this was the end point for their occupation.

JOHN HAMILTON: I disappeared back to Wellington. The role of national controller had by that stage been stopped, so all the authorities I had as national controller were relinquished. CERA was set up and Roger Sutton took over.

GINA IRISH: The demolition of the Gallery Apartments felt like quite a momentous event for the staff. We all knew the apartments needed to go, they were red-stickered, and their demolition meant that the Gallery was one step closer to being reopened. We cracked into moving the collection quite quickly and it should have felt like a daunting task but I don’t remember it being like that. It was a major mission. Collections don't typically move from stores; it's unheard of to move your entire collection unless you are going through refurbishment or redevelopment.

The Gallery Apartments next to the Gallery being demolished. Photo: John Collie

I was absolutely clear that if we didn’t attend to the building and make it absolutely optimal we would be out of the exhibition circuit.

SEAN DUXFIELD: I pushed very hard that the collection should stay on site. We didn’t have the time or resources to pack it properly or safely, and there wasn't a venue anywhere in the South Island to take it that had temperature and humidity control, 24-hour alarms, security, fire suppression, and all the things we had in place in the building already. We shifted the whole thing in six weeks.

NEIL SEMPLE: It was a massive undertaking. Every piece of artwork that we have in the stores was moved down to the touring galleries on the ground floor, because we were able to climate control those areas. The whole collection was shifted piece by piece into the goods lift and across the foyer into those spaces.

SEAN DUXFIELD: It was a big game of Tetris really. We mapped it, and just started filling the place, making racks and cobbling together temporary storage systems.

GINA IRISH: The designers came up with huge plans for the space. A bit like what they do when they're designing an exhibition, but this was on a grand scale. We had paintings covering the walls in a salon hang so they could be stored safely. Shelves had to be built, shelves from storage had to be decanted, taken downstairs, and objects put back on those shelves. And of course we were still in a very active aftershock sequence so the collection had to be checked regularly; everything had to be strapped down, chocked, or blocked; and hangers had to be seismic-proof.

NEIL SEMPLE: The process of repairing the building went through a number of false starts. Initially we thought that once Civil Defence had done their job and left the building, we'd be able to paint the walls and hang the art and throw open the doors again, but it slowly became clear that the building was a little sicker than we'd first thought.

BLAIR JACKSON: We never anticipated that the building was actually that damaged. Everyone thought it was amazingly strong, but as time went by and there were geotechnical investigations into the ground underneath, the full extent of the damage became known. There was a sense of safety; the building had gone through regular inspections after every earthquake over a magnitude 5, as engineers were concerned about the space that Civil Defence were in. But as time went by the focus moved to how much damage there was to the building and what it was going to take to repair it.

MICHAEL AITKEN: So then we got into a lot of argy-bargy about what to claim for in the insurance—what the insurance will pay for and what the policy really said. There were some wide-ranging discussions but pretty rapidly we got to the fact that we needed to get the Gallery up and running, and it needed to be right. We had a lot of discussion about base isolation. After going through multiple forms of Council discussion that's where we got to in terms of the repair strategy. Let's get it back up and running and let's get it in a better state than it was. The key thing we thought about is the function of the Gallery in the life of the city.

I've heard Jenny's speech about how poorly endowed this gallery is because we didn't start collecting early enough. We live on exchange; we live on borrowing. The Ron Mueck exhibition is a great example. You bring in the right exhibition and you change people's lives, you break barriers for people with art. If that isn't what we're in the business of doing I don't know why we're open.

JENNY HARPER: I was absolutely clear that if we didn’t attend to the building and make it absolutely optimal we would be out of the exhibition circuit. And I suppose having come from Wellington where there were examples of retrofitting of base isolation I knew it was possible, and I did a lot of research into retrofitting of base isolation in international museums. At first it looked as if the base isolation would be enough on its own. It was probably during this time that we became more conscious of the fact that the ground was going to need remediating as well as the building. The ground had settled in a different formation.

NEIL SEMPLE: The building had settled differentially; from what I recall it's a total of 150mm across the plate. This company Uretek came in with a highly technical kind of ground engineering, and effectively floated up the building to be level again.

RUSSELL DELLER: The technology we were bringing to Christchurch was new to this part of the world, though it had been used in Japan. We combined two technologies that had never been used in conjunction before; the jet grout for creating the columns underneath the Gallery and the JOG computer system for re-levelling it. One of the challenges was the high tensile steel rods—ground anchors—that had been put down there during construction to hold the floor slab down so that it didn’t float up. Some of them had worked in compression, which means when the building was sinking some of them were actually stopping sections from settling. When we lifted the building we had to release these anchors. We were about a metre and a half below the water table where we were working—effectively we were working underwater.

The jet grout columns have created a soil block which has provided some future proofing, and a strong enough reaction platform to lift the building. We installed robotic stations and monitored the building at over 350 locations so we could see every aspect of the building as we were moving it—and make sure it was floated up gently. When the building started to move—in a controlled way—we could all breathe a sigh of relief; everything we'd designed and engineered and thought about was OK, and the result was outstanding. Then Fulton Hogan separated the above ground structure from the in ground foundations. In a future event—due to what we've done to the ground—the ground is more stable, and any energy that's transferred through the building can move independently from the ground. Really, it was a feel-good—being able to save a building that was quite iconic in Christchurch.

The robotic stations monitoring the movement of the building during the re-levelling process. Photo: John Collie

DONAL BUCKLEY: My first impressions when I came onsite were almost of sadness. When you get into a building of such public significance and see it standing empty with the art held in one room, contained and stacked, it brought home the massive impact that the earthquakes have had on the community as a whole. My immediate reaction was that it's such a shame to see a building of this size sitting there empty. It probably reflects the city centre as a whole—it was empty, and needed to be brought back to life.

I got involved as we were just about to start the design and procurement of the base isolation. It was quite a tough project to get immersed in—the vastness, and the different number of work streams involved in it.

BEN HARDY: For its scale, it's a very complex project. Base isolation technology is complex enough when you're starting an new build, but when the building already exists there's lots of hurdles that need to be overcome. We used 140 bearings in the building. While half were used in a routine way, inserted into each of the 70 columns in the basement, the other 70 were all bespoke solutions to individual problems; where there are stairs, for example, or a lift shaft, or the back of the building where there's no basement at all.

From a construction point of view, it's been really hard work for the guys that have been out there. A lot of concrete breaking, and noise, and dust; pretty brutal, really. They've put their heart and soul into doing the work, and everyday those guys on the tools go home, they know they've done a hard day's work—but with that comes a lot of pride.

There was a chap—Juan, who was travelling around the world, working with us for six months—who scabbled images on to the columns in the basement. And it was wonderful how well that was received from outside and latched on to as being of value, as a contribution that was worth recording. I guess it challenged a few people's ideas about where art can come from, and who can be an artist. He started that on one of his smoko breaks, mobile phone in one hand, pen in the other. And it turned everyone on to the fact that this wasn't just a retail building, or an office block. It's more than that.

DONAL BUCKLEY: It quickly became apparent that the Gallery team were very protective of their building, and I suppose this was amplified by the fact that the art was still stored onsite. They protected it like it was their children, and that rubs off on the rest of the project team. You feel that you're there to act as part of that protection process. As much as bring the building back to life there's a primary directive to also protect the art.

SEAN DUXFIELD: My role was really to be the voice of the collection; to make sure whatever was proposed in terms of the building repair didn’t impact on the collection; or if it did have an impact, that it was minimised. The collection had to stay where it was, and that was completely non-negotiable in terms of the repair. Often it meant physically moving things away from a wall or from below a ceiling, draping or covering things with cardboard or plywood sheets.

LYNLEY McDOUGALL: We had a very thorough risk strategy for managing the artworks, the security, and the shell of the building while they were doing this work. A few struggles; but you just have to look forward and keep the communication going. Managing the plant is very complex, and it's vital to keep the environment stable to care for the artworks. The Gallery's like a mini-environment separate to the outside world, a breathing organism. But around it you've got all this massive mechanical and electrical activity going on with the civil engineering. It's something that's been quite unique.

BEN HARDY: We've had to take a lot of care in the sequencing of work so that we've always been able to maintain the appropriate services to keep the art in the right environment. I think we can say at this point we've succeeded.

GINA IRISH: As registrars you're quite risk averse: that's your job. There's nothing more terrifying than having your collection in a building that's effectively a construction site. I'll sleep easier when we get the keys back and the contractors move out.

Collection artworks in temporary storage. Photo: John Collie

It's the first major reopening of a civic building after the earthquakes. I think this reopening is going to be very important to the city.

BEN HARDY: I'll remember the project for the continual rattle of concrete being broken out and scabbled and drilled. The sheer energy of the workforce that's gone into transforming the building from one type of building to another. And after all that time in the transformation, we'll end with a building that looks the same. It's one of those projects where the ultimate goal is making no apparent change at all: a lot of effort has gone into being as unobtrusive as possible.

DONAL BUCKLEY: A challenge has been conveying the level of activity and complexity of the work involved in the project. To anyone walking past on the street you don’t see a huge amount of activity, but at any given time there could be 150 guys in the basement cutting concrete and steel. Managing people's expectations across all of the stakeholders on the project has been a particular challenge. Jenny put out a quote to me last weekend: ‘we love you, but we want you out of our building’.

JENNY HARPER: I long to see the building open and busy with people. I think the building will be fantastic. I'm sorry we couldn't have done some of the things we'd like to have done while it was closed because there were things we could have changed to everyone's advantage. Unfortunately the time it's taken to sort insurance matters has meant that we really haven't had the option.

BLAIR JACKSON: Having had no involvement in the original planning of the building I've often tended to see its weaknesses—the bits that make exhibitions or public access difficult. But all I see now is the strengths of the building and the opportunities of what we could be doing with it.

SEAN DUXFIELD: The funny thing is that when we reopen you won't see the enormity of the scale of what's gone on. It will just look like it always did bar a couple of minor cosmetic things. But the fact it's just a better building will be significant enough.

BEN HARDY: The end of the project is coming over the horizon very quickly now. It might be a bit surreal when it actually happens.

MICHAEL AITKEN: When we welcome people back I think it will be a psychological milestone for people. It's the first major reopening of a civic building after the earthquakes. I think this reopening is going to be very important to the city.

DONAL BUCKLEY: We've always found a way to get the best for the project. One case in point is the latest piece of art that we got up on the building, ‘everything is going to be alright.’ It was quite late in the piece, but Jenny came in and just said we want to get this up, can you do it? With a little bit of coaxing from Jenny everyone bought into the whole process and it's amazing, with a little bit of cooperation a huge amount can be achieved. For a three week period all politics that you would usually associate with a contract process were put aside and everybody did what they needed to get this up on the wall. When it was unveiled, it was a very uplifting moment for everyone involved. It sends a message not only to Christchurch but to the project team. We all need to pull together and look at the positives, and when you have that literally written over your head it drives it home.

JENNY HARPER: One of the things I was very pleased about between the September and February earthquakes—as well as Ron Mueck—was that we'd started writing a vision. What we actually wrote was a manifesto. But it doesn’t talk about a building. It talks about why we're here and what we do and what our relationship with artists is and how we set standards and do great things, and break rules—even our own—and I reckon that has helped us no end over the past five years.

Jenny Harper with some of the Fulton Hogan team working to ensure the Gallery is open on 19 December. Left to right, Pete Colombus, Jae Taueki (seated), Jordan Anderson, David Shelley, Richard Newland, Dennis Casey, Amy Stewart, Jenny Harper, Frank Prendergast, Buster Clarkson, Jade Sibley. Photo: John Collie. With thanks to Fulton Hogan

Contributors to oral history

The people interviewed for this article are:

Lynley McDougall, Christchurch Art Gallery Visitor Services and Facility Manager.

Michael Aitken, former Christchurch City Council Community Services General Manager. The Gallery operates as part of the Council’s Community Services division, now Customer and Community.

Blair Jackson, Christchurch Art Gallery Deputy Director.

Neil Semple, Christchurch Art Gallery Projects Manager.

Jenny Harper, Christchurch Art Gallery Director.

Sean Duxfield, Christchurch Art Gallery Exhibitions and Collections Team Leader.

John Hamilton, former Civil Defence National Controller. Civil Defence coordinated the disaster response to the earthquakes, and established the Gallery as Civil Defence headquarters.

Donna Robertson, editor of the Christchurch City Libraries' web team. Donna was part of the group that coordinated Christchurch City Council online communications to the public from the Gallery after the earthquakes.

Gina Irish, Christchurch Art Gallery Registrar.

Russell Deller, Mainmark Ground Engineering General Manager. Mainmark (formerly Uretek Ground Engineering) re-levelled the Gallery building.

Donal Buckley, Greenstone Group and Greenstone Pace Project Director. Greenstone Pace project managed the re-levelling, base isolation and earthquake repairs throughout the Gallery.

Ben Hardy, Fulton Hogan, Civil Operations Manager, Southern Region. Fulton Hogan completed the base isolation retrofit and insurance repairs to the Gallery.