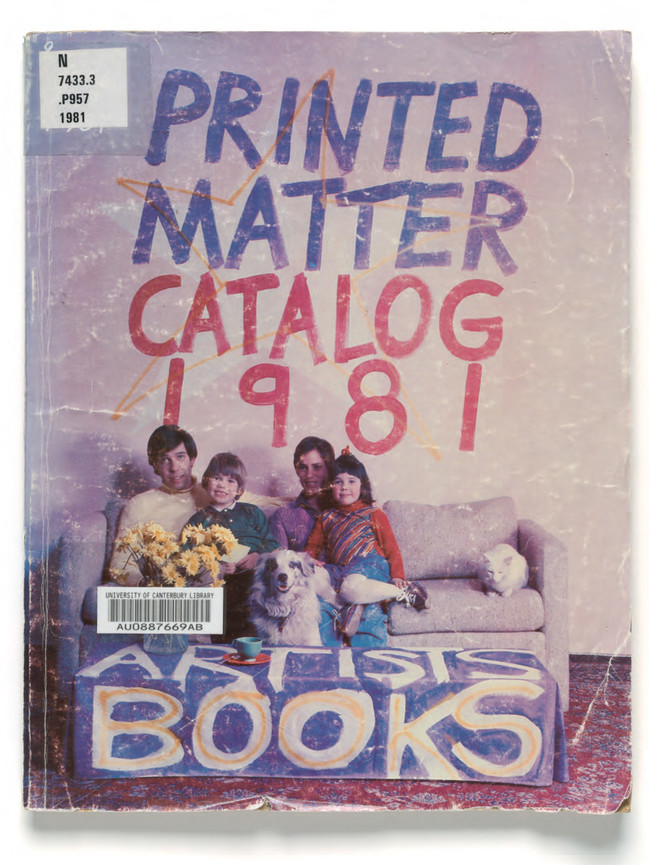

Detail of Printed Matter Inc.: Books by Artists, New York: Printed Matter, 1981

The book as alternative economy and alternative space

In Printed Matter's 1981 mail-order catalogue, artist Edit deAk enthusiastically described the 'many hands at work in the process of making and marketing the book'.1 Turning the spotlight on individuals and groups involved in the production, distribution and sale of books by artists, deAk likened independent art publishing to activities 'like filmmaking or rock 'n' roll music.' While such comparisons with filmmaking have been relatively scarce over the past few decades, artists, publishers, designers and critics have continued to draw parallels between art publishing and independent music.

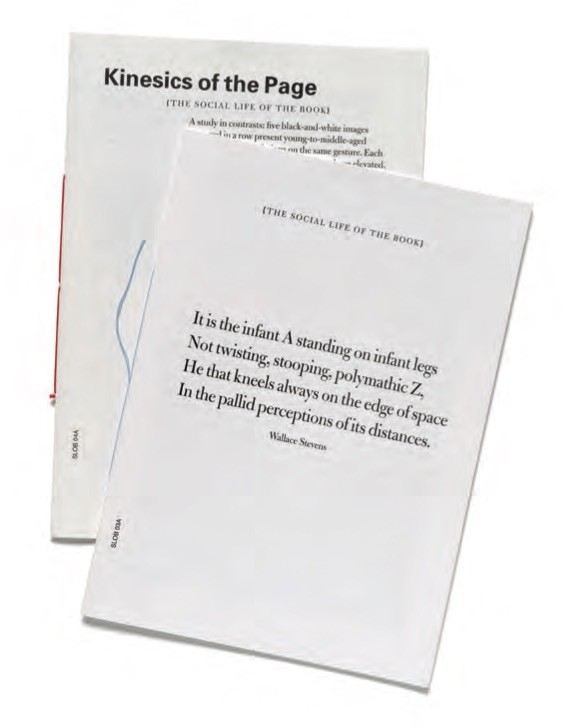

In his introduction to KIOSK Modes of Multiplication: A Sourcebook on Independent Art Publishing 1999–2009, Moritz Wullen, deputy director of the Kunstbibliothek in Berlin, describes a ‘scene ... aptly named “independent publishing” – following the model of the musical avant-garde – which, since New Wave and Punk, has distinguished between the major labels and eccentric labels with religious zeal.’2 And Paraguay Press, an imprint of Parisian bookshop castillo/corrales, is currently publishing a parallel series of small booklets exploring the ways books and records engage in social situations. Entitled The Social Life of the Record and The Social Life of the Book, each limited-edition booklet includes contributions by writers, artists, designers and booksellers or musicians, fans, critics, collectors, dealers and record-label owners respectively, who trace the relationships between making and distributing independent books and records today. As disparate as these examples are, each emphasises the spirit of collectivity, counterculture and resistance that continues to drive independent music and artists’ publishing. Moreover, they point towards the almost idiosyncratic manner by which books and music spark collaboration and connectivity through their production and distribution, generating similar relationships between artists and producers, distributors, stores, fans or audiences. Existing at the intersection of disciplines and creative practices such as graphic design and literature, publications by artists provide opportunities to exploit and expand such networks.

Art publisher and designer Christoph Keller explored the egalitarian qualities of the book medium in an open letter to a colleague in 2008, proposing that ‘books make friends’ – a line that has since been quoted frequently within discussions of independent art publishing, and positions friendship and connection as its own form of currency.3 Though this sentiment has been prevalent in the field of independent publications for quite some time, it is particularly relevant within the current digital and global context of contemporary art and exhibition culture, where publishing communities have been mobilised by international distribution networks as well as partnerships between institutions, websites and online bookstores.

Louis Lüthi, Infant A, The Social Life of the Book #03, Paris: castillo/corrales, 2012, and Avigail Moss, Kinesics of the Page, The Social Life of the Book # 04, Paris: castillo/corrales, 2013

Comparison between books and music also points towards the underlying desire to generate alternative economies outside of established traditions and institutions within the cultural sphere. The very labels 'independent publishing' or 'independent music' denote some form of emancipation from the compromises or value-systems of their mainstream counterparts – an idea that formed a large part of the impetus for the historical development of artists' publishing. During the 1970s and early 1980s, many artists and critics exploited different types of printed matter in order to try and circumvent the art market and gallery system. Lucy Lippard described books produced by artists around this time as 'a declaration of independence by artists who speak, publish and at least try to distribute themselves.'4

The term 'democratic multiple' emerged in the 1970s to encompass inexpensive, multiple-edition booklets, postcards, artists' books and pamphlets exploiting commercial production methods. The label originally celebrated books and other printed multiples for their affordability, accessibility, and their ability to be multiplied and distributed on a larger scale, qualities that related back to an underlying hope that these objects would reach and enchant a broader public. Yet critics such as Lippard, a founder of Printed Matter and one of the chief proponents of the democratic multiple, began to critique some of these ideas as early as 1983. In her essay 'Conspicuous Consumption: New Artists' Books', Lippard noted that during this time, 'despite sincere avowals of populist intent, there was still little understanding of the fact that the accessibility of the cheap, portable [book] form did not carry over to that of the contents.'5 While the publications may be cheap and readily accessible, the ability to engage with these works frequently requires institutional framing or inside knowledge of the art world and art history.

The idea of emancipation continues to conflict with some of the social and economic realities of producing and distributing books and printed matter. In today's climate of art publishing, individual projects often exist within complex networks of artists, designers, publishers, booksellers, distributors, curators, museums, galleries and funding bodies. As each of these parties hold their own ideals and agendas, a certain amount of bargaining must take place to get publications off the ground. Moreover, while independent art publishing projects may not be commercially driven, or sometimes even commercially viable, they may be deeply embedded within other economies, such as education and public arts funding, where they act as forms of currency. As collectable, fetishised objects that require a certain level of cultural capital to engage with, independent publications are certainly part of the mass-market of cultural commodities. Indeed, perhaps one of the unique characteristics of artists' publications is the way they tread the line between elitism and exclusivity, collectivity and popular values.

The tensions and political possibilities of distributed media have long provided fertile ground for artistic enquiry. From the manifestos of the Modernist avant-garde, to mail art and artists' books, to new-media works that engage with communication technologies, distribution and circulation are definitive paradigms of twentieth-century art history. While a larger print run or wider distribution circle did not necessarily allow artists and publishers to achieve the goals of the 1960s and 1970s, the possibilities of multiplication and distribution continue to drive independent art publishing in the post-internet era. A new generation of artists, designers and writers is producing publications that are democratically available, free or inexpensive and sometimes produced both online and in print. Contemporary artists are exploring distribution strategies in order to meet or resist some of the common goals, demands and preoccupations of artistic production in the twenty-first century.

Some of these strategies are explored by artist Seth Price in his well-known essay Dispersion (2002). Price considers how artists engage with 'the material and discursive technologies' of distributed media in order to interrogate 'the circuits of money and power that regulate the flow of culture'.6 He argues that in order to think about the dispersal and circulation of art in the post-internet era, we must re-think the idea of what is public: 'publicness today has as much to do with sites of production and reproduction as any supposed physical commons, so a popular album could be regarded as a more successful instance of public art than a monument tucked away in an urban plaza.'7 While it is important to recognise the new means and mediums of communication being used by artists to circulate their work, we must also consider how new media influences the formation of publics.

Printed Matter Inc.: Books by Artists, New York: Printed Matter, 1981

‘The ability of books to travel and to act as an

alternative space for art holds particular significance

for New Zealand artists, curators and writers, who continue to use publishing as a way to generate an international presence, and as a resourceful way to participate in social networks of production and presentation beyond our immediate geographical surroundings.’

As a medium that challenges conventional art-world boundaries between production and distribution, books provide opportunities for artists and publishers to create their own rules of engagement with audiences. Artist and educator Maria Fusco explored this idea in 2008, when she characterised her own print-based projects as employing similar methodologies of dissemination and distribution to 'folksonomic tagging – the little blue tags on Wikipedia pages where you can link to other sections', allowing developers to create more intuitive pathways through the website.8

She argued:

There is something interesting ... in how you interest people in your work, how you create an audience for your work and how you sustain an audience for your work. Here's a quote from Michel de Certeau from The Practice of Everyday Life: 'The means of diffusion are now dominating the ideas they diffuse'. That is a very interesting quote, certainly for the practice of artists' books, where you are looking at something that by its very nature is metacritical, or is reflecting, or looking, or pointing back at its own conventions of form.9

Rather than imagining their books somehow finding their way into the hands of a general public (the ultimate goal of a previous generation of artists), independent publishers and artists now tend to address curious, like-minded readers, who work, study or socialise within similar circles. Los Angeles-based artist and writer Frances Stark goes as far as describing herself as the ideal audience member for her own limited-edition publication, The Unspeakable Compromise of the Portable Work of Art: #16 in a Series of 16, THIS WHOLE THING, or, A Bird's Eye View (2002).10 She compares her publication to a letter to her audience, noting that 'letter writing is a lot about how well you know who you're writing a letter to'. She writes: When putting together this book ... I was really trying to think about the immediate, receptive audience for my work; dealers, curators, other artists that I interact with. Sometimes you don't even know whether your closest friends are in your audience or not. That is what has always bugged me about this so-called art world. Unless you're a Type-A omnivore and/or a high energy sycophant, the 'art world' (probably a bad habit word to begin with) can easily be stripped of your most sympathetic patrons and morph into a hateable panel of semi-anonymous pseudo experts against whom you feel forced to rebel. I would much rather get to know, understand and communicate with the audience I have built as these are the meaningful relationships which shape my world. 11

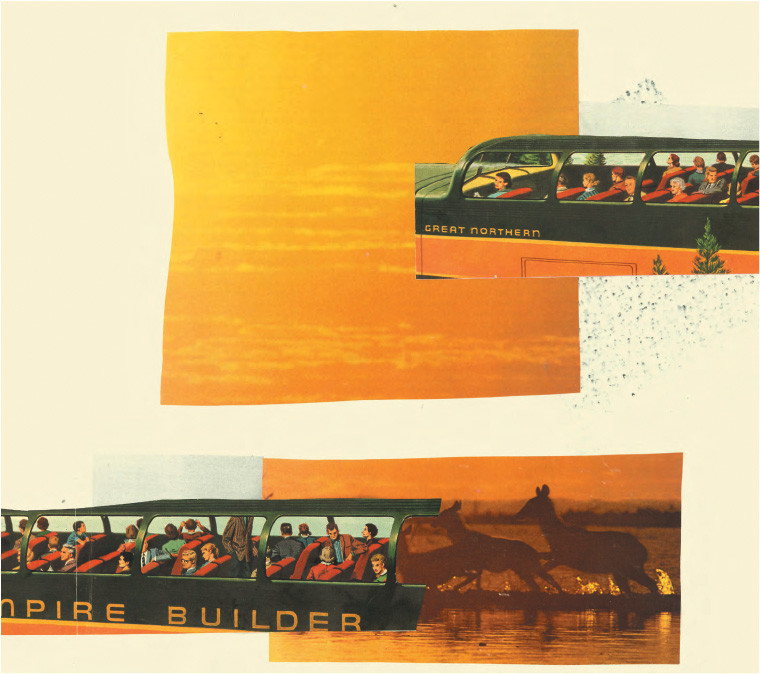

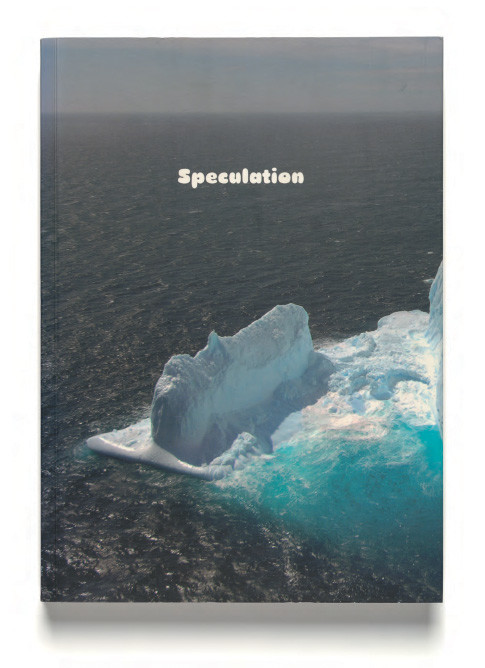

Brian Butler (ed.), Speculation, Zurich: JRP Ringier and the Venice Project, Aotearoa New Zealand, 2007.

Stark uses her publication to draw our attention to the various social and professional networks that support her artistic practice. Furthermore, she suggests that the knowledge of such networks is necessary for a reflexive and critically engaged art practice as the audience becomes a focus of her writing.

Yet audiences for publishing projects are also generated through strategic partnerships with institutions, funders and other publishing houses. Within the international ecologies of the art market, public funding channels and the gallery and education systems, different actors create distribution channels, new audiences and financial support for independent art-publishing projects. Currently, one of the priorities of New Zealand's own arts-funding agency Creative New Zealand is to support initiatives that build relationships with communities overseas – a goal which encompasses international residencies, touring exhibitions and postgraduate study in overseas institutions, as well as publications. Within this context, books are often employed as economic vehicles to 'export' the work of New Zealand artists, or to relay a new body of work from expat artists to audiences back home (recent examples include publications by Simon Denny, Ruth Buchanan and Michael Stevenson).12 The ability of books to travel and to act as an alternative space for art holds particular significance for New Zealand artists, curators and writers, who continue to use publishing as a way to generate an international presence, and as a resourceful way to participate in social networks of production and presentation beyond our immediate geographical surroundings.

The book Speculation (2007), edited by Brian Butler, is perhaps the best-known example of this phenomenon in recent New Zealand art history. Speculation was produced in place of a New Zealand Pavillion at the 52nd Venice Biennale, while government funding was under review and its future uncertain. Rather than have no representation from New Zealand at Venice, eight curators each selected a group of artists they believed could be sent to future biennales, pointing towards a series of potential projects which could take place if funding and support was allocated. The book's cover includes an aerial photograph of icebergs that appeared off the coast of Dunedin in November 2006. Evocative of air travel and geographical remoteness, it illustrates our fixed location at the 'edge of the world' – a familiar preoccupation of New Zealand artists such as Julian Dashper – in juxtaposition with the portability of the book itself. A quote from Ernest Rutherford on the first page reads 'we don't have the money, so we have to think', emphasising the possibilities of critically engaging with the pragmatics or limitations of presenting and circulating artwork.13

By inviting us to consider various tensions and possibilities within this global, digital and increasingly professionalised sphere, independent publishing is playing a new role within a contemporary art landscape. Books developed in collaboration with designers, writers, publishers and institutions often establish their own economies of exchange that also determine how audiences are generated. Although these works embody a certain spirit of resistance, they are also aware of their own complicity within systems of cultural currency. And by merging sites of production and distribution, practitioners are able to engage independent publishing in its most dynamic form – a generative and collaborative activity that develops a public.