Petrus van der Velden: He haemanga maunga, Te Āpiti o Otira

Petrus van der Velden: He haemanga maunga, Te Āpiti o Otira

Na te reo o Te Mihinga Komene Petrus van der Velden He haemanga maunga, Te Āpiti o Otira (1893).

Related reading: McCahon and van der Velden

Exhibition

Van der Velden: Otira

11 February – 22 February 2011

This exhibition brings together a comprehensive selection of Van der Velden's paintings portraying the wild, untouched natural beauty of the Otira region's mountainous landscape.

Notes

Canterbury Landscape by Colin McCahon

In 2014 we purchased an important landscape work by Colin McCahon. Curator Peter Vangioni speaks about this new addition to Christchurch Art Gallery’s collection.

Article

Gazumped

One of the exhibitions brought to a halt by the 22 February earthquake was De-Building, which critic Warren Feeney had described only days earlier as 'Christchurch Art Gallery's finest group show since it opened in 2003'. Seven months on, the show's curator, Justin Paton, reflects on random destruction, strange echoes, critical distance, and the 'gazumping of art by life'.

Interview

Otira: it's a state of mind

A short road trip to the Otira Gorge was the scene for a conversation between Gallery curator Peter Vangioni and two of the artists included in Van der Velden: Otira, Jason Greig and the Torlesse Supergroup's Roy Montgomery.

Article

Van der Velden: Otira

A first encounter with a painting by Petrus van der Velden more than twenty years ago was the start of many years of research for Gallery curator Peter Vangioni. Peter is the lead author of the Gallery's new book on van der Velden, and talks here of his fascination with the artist's Otira works.

Collection

![Burial in the Winter on the Island of Marken [The Dutch Funeral]](/media/cache/58/29/58295f2c69a43061863860a247424aba.jpg)

Petrus van der Velden Burial in the Winter on the Island of Marken [The Dutch Funeral]

Research for the exhibition Closer (16 December 2017 – 19 August 2018) resulted in the restoration of this work's orginal title. In Dutch 'Begrafenis in den winter op het eiland Marken' and in English 'Burial in the winter on the island of Marken'.

Combining a wintry landscape with an equally bleak portrayal of loss, this painting has captivated many visitors since joining the Gallery’s collection in 1932. Small details, like snow-dusted shoes, noses red with cold, and a woman folded over by grief, are observed with such accuracy and tenderness by Petrus van der Velden that this funeral procession on an isolated Dutch island feels just as real as it looks. However, its most important figure – the reason for the gathering and for all the grief we see – remains unseen. The deceased, said to have been a drowned local fisherman, is present only in the dark shape of the coffin – and in the faces of those left behind.

(Absence, May 2023)

Collection

Colin McCahon Van Gogh: Poems by John Caselberg

Colin McCahon produced his first lithograph in 1954, and in 1957 completed two suites of lithographs, including Van Gogh – poems by John Caselberg. He employed a commercial lithographer for these works with mixed results, likely due to the fact that he had little say in quality control with the printer. Nevertheless, it was ultimately a successful suite. Colin incorporated John Caselberg’s poem sequence, ‘Van Gogh’, into his drawings, writing the poem out across several sheets in his iconic handwriting, which he also usedin his paintings. Colin also worked with other print mediums, including a small potato print also in this exhibition, but it is his lithographs from the 1950s that were his most successful.

Ink on Paper: Aotearoa New Zealand Printmakers of the Modern Era, 11 February – 28 May 2023

Collection

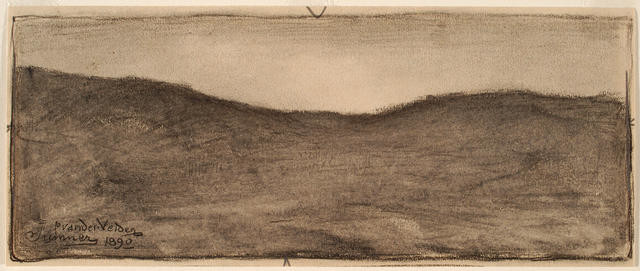

Petrus van der Velden Mount Rolleston and the Otira River

Talking about his first visit to Ōtira in 1890, Rotterdam-born artist Petrus van der Velden later recalled, “For the first three days I did nothing at all but just looked, it took my breath away.” A highly skilled professional artist with substantial exhibiting experience in the Netherlands, van der Velden prioritised capturing or expressing emotion in his art over recording the physical features of the landscape. The awe-inspiring setting aided him in this pursuit – especially during stormy weather – and drew him back again and again.

He Kapuka Oneone – A Handful of Soil (from August 2024)

Collection

Colin McCahon Blind V

The word ‘blind’ refers to a screen that cuts out light, but Colin McCahon also uses it to refer to an absence of vision. Questions of faith were important to McCahon and he often used references to blindness to suggest the inability to see the real essence and value of things. McCahon’s style was highly personal and distinctive. Blind V is part of a series of five works painted onto window blinds. The abstract forms have the feel of a beach and sky and it has been suggested that the ‘blindness’ which McCahon refers to was the inability of New Zealanders to really see and appreciate their own unique environment.

McCahon is regarded by many as New Zealand’s greatest contemporary artist. Born in Timaru, he studied art in Dunedin. He lived in Christchurch for a time, became keeper and assistant director at Auckland Art Gallery, then lecturer in painting at the Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland, before taking up painting full time in 1970.

Collection

Petrus van der Velden Sumner

“Colour is light, light is love and love is God and therefore on Sundays instead of going to church I teach my children drawing after nature. I have come to the conclusion that painting or drawing after nature, instead of being a luxury is the most necessary for the education of man. […] The aim of our existence is nothing else than to study nature and with so doing to understand more and more how grand and pure nature is and gives evidence of so much love.”

—Petrus van der Velden

(McCahon / Van der Velden, 18 December 2015 – 7 August 2016)

Collection

Petrus van der Velden Nor'western Sky

“‘Colour is light’ and there is no darkness at all – there is light or less light. In each part, even the darkest, there is some light and the difficulty is to get the different kinds of light showing in even quite small parts. There are no hard lines in nature – the light shines in and round everything and breaks all the hardness by modifying and diffusing the apparently sharp edges.” —Petrus van der Velden

(McCahon / Van der Velden, 18 December 2015 – 7 August 2016)