Martin Rumsby interviews Tony Fomison

Martin Rumsby interviews Tony Fomison

Tony Fomison comments on his approach to his work in an interview with Martin Rumsby recorded in 1980. The recording was kindly supplied by the Alexander Tunrbull Library and is reproduced here with the generous permission of Martin Rumsby.

Source: Alexander Turnbull Library OHInt-0813-08

Related reading: Ka Honoka, exhibition-1012

Exhibition

No! That's wrong XXXXXX

25 June 2016 – 30 April 2017

Three paintings by Tony Fomison, Philip Clairmont and Allen Maddox.

My Favourite

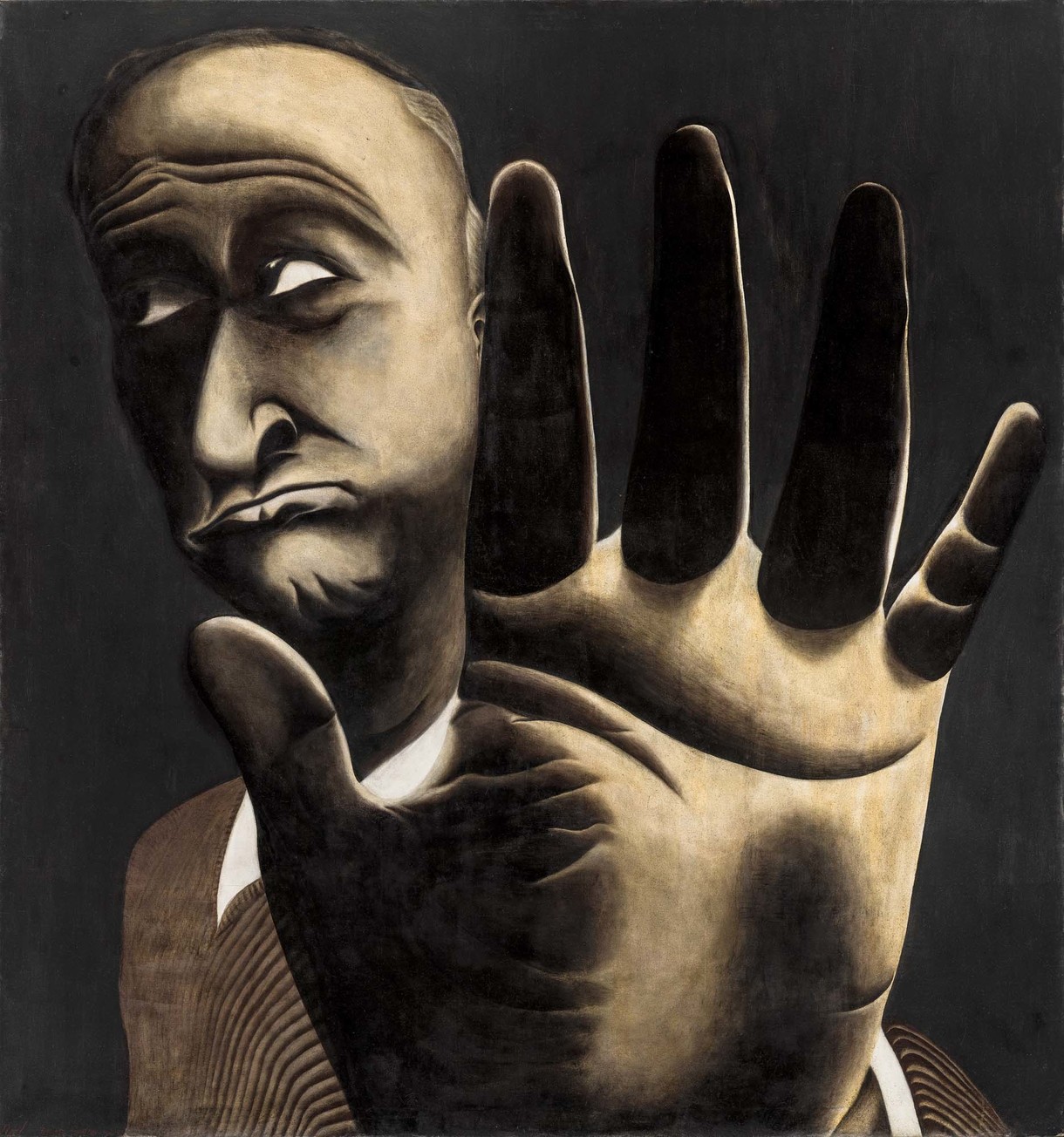

Tony Fomison's No!

I’ve chosen this because it’s probably Tony’s best-known painting (it’s the one that the Gallery chose to upsize onto an inner-city wall) and because it’s emblematic of his art, which was confrontational and definitely not user-friendly. In a long profile I wrote of him in the 1970s he said of his middle-class patrons: ‘I’ve got a bee in my bonnet about them. They’re the swine I rely on to buy my paintings. I hope these paintings fester on their walls and they have to take them down and put them behind the piano. I hope the paintings get up and chase them round the house.’

Notes

Happy Birthday Akaroa Museum

Big Congratulations to Akaroa Museum on their 50th anniversary which they are celebrating this weekend.

Article

A Tale of Two Chiefs

If you have recently visited He Taonga Rangatira: Noble Treasures at the Gallery you will have been struck by Fiona Pardington's two large photographic portraits of lifelike busts of Ngāi tahu tipuna (ancestors).

Collection

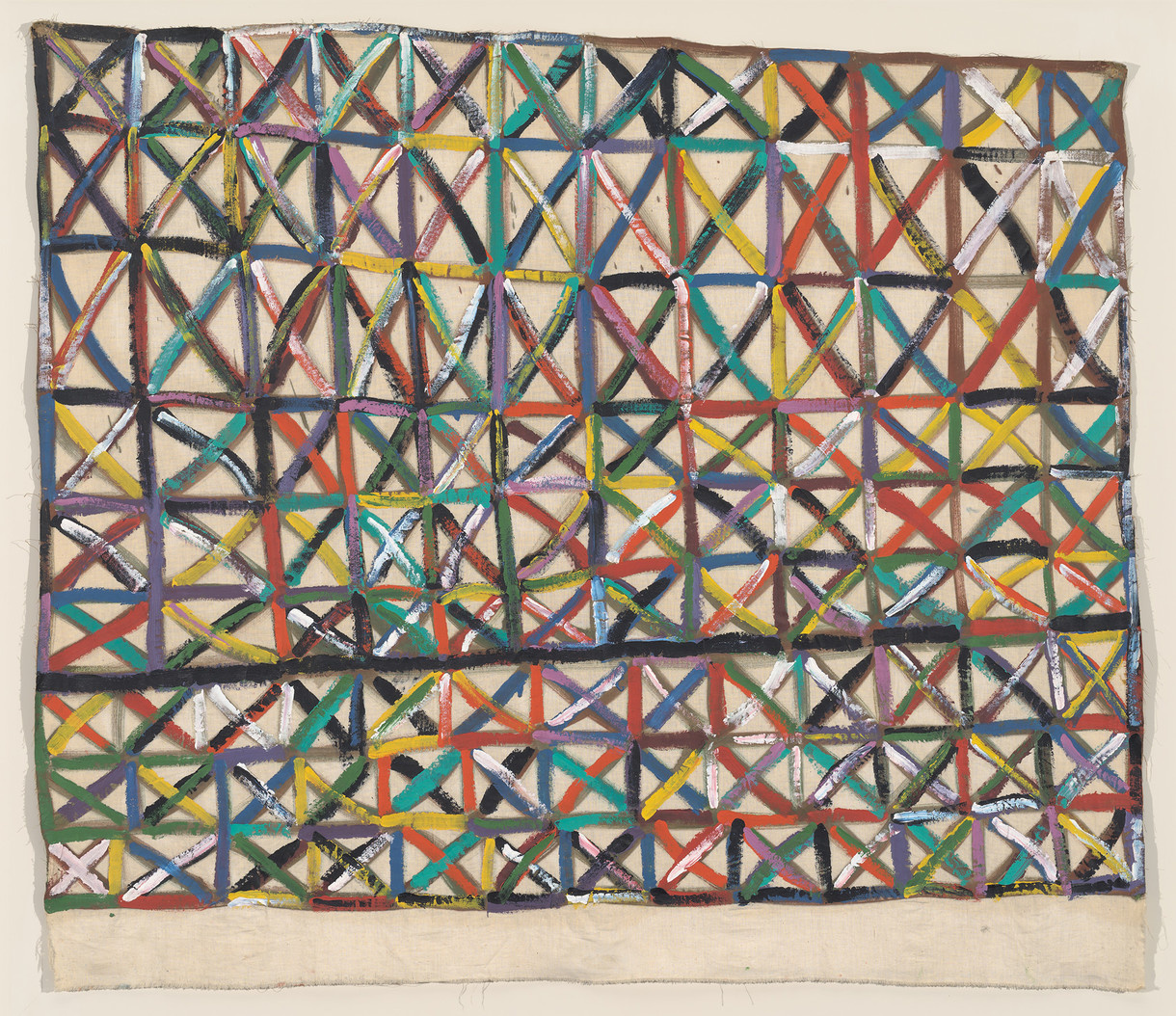

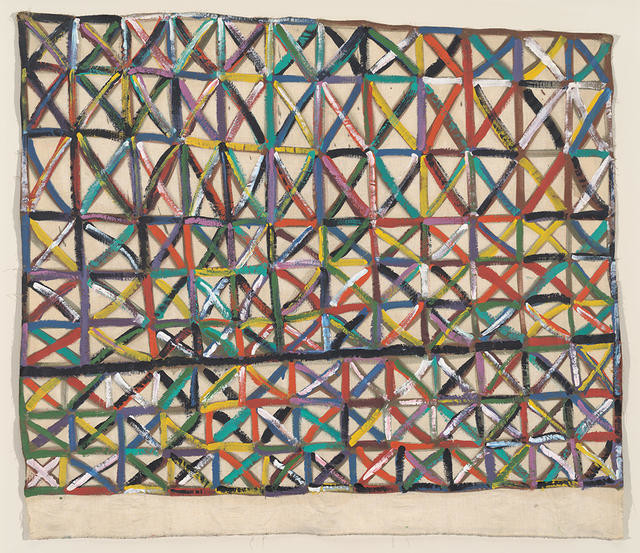

Allen Maddox No Mail Today

Allen Maddox began producing his well-known ‘X’ paintings around 1975 when, in a moment of despondency, he angrily defaced a painting he was working on with an X. The motif stuck, and he began repeating his 'crosses in boxes' over and over on his canvases. There is a compulsiveness in Maddox’s ‘X’ paintings; at once ordered yet disordered, they demonstrate a combination of gestural boldness and neurotic energy. Maddox commented in 1977 that he ‘would like to be able to visually reproduce the little electric thought patterns that go on in your head when one is paranoiac… How I thrill to a composition resolved by “painterly” means. Splashes, strokes, aesthetic errors.’

(No! That’s wrong XXXXXX, 25 June 2016 – 30 April 2017)

Collection

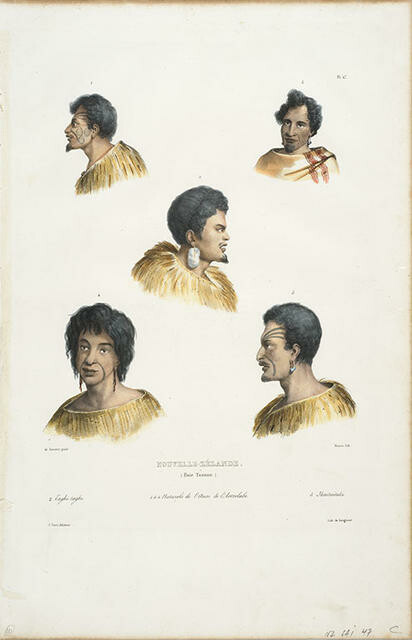

Louis Auguste de Sainson Nouvelle-Zélande

Louis Auguste de Sainson was the official artist aboard Captain Dumont d’Urville’s Astrolabe. He spent three months in New Zealand in 1827 on a maritime mapping survey between Tasman Bay and the Bay of Islands, followed by a month in Tonga. A substantial publication on d’Urville’s 1826–29 voyages through Asia and the Pacific was published in Paris in 1833, profusely illustrated by lithographic prints after de Sainson’s drawings.

D’Urville and his crew had close contact with people they met, including the Totaranui chief Tehinui (or Tehi-Noui) and his travelling companion Kokiore (or Koki-Hore) depicted in print 2, who were sketched by de Sainson after coming aboard at Palliser Bay (near present-day Wellington). Tehinui and Kokiore at first both intended to reach Europe, but instead disembarked at Tolaga Bay, later finding their own way home. In summarising his portrait sketching process, de Sainson later recalled: “What I was doing caused a lot of laughter; every minute they tried to escape me.” (Kā Honoka, 18 December 2015 – 28 August 2016)

Collection

![Nouvelle-Zélande - coffre en bois sculpté [Plate 59]](/media/cache/74/c2/74c2c0a963376af9e77d5765ca8842be.jpg)

Louis Auguste de Sainson Nouvelle-Zélande - coffre en bois sculpté [Plate 59]

Louis Auguste de Sainson was the official artist aboard Captain Dumont d’Urville’s Astrolabe. He spent three months in New Zealand in 1827 on a maritime mapping survey between Tasman Bay and the Bay of Islands, followed by a month in Tonga. A substantial publication on d’Urville’s 1826–29 voyages through Asia and the Pacific was published in Paris in 1833, profusely illustrated by lithographic prints after de Sainson’s drawings.

D’Urville and his crew had close contact with people they met, including the Totaranui chief Tehinui (or Tehi-Noui) and his travelling companion Kokiore (or Koki-Hore) depicted in print 2, who were sketched by de Sainson after coming aboard at Palliser Bay (near present-day Wellington). Tehinui and Kokiore at first both intended to reach Europe, but instead disembarked at Tolaga Bay, later finding their own way home. In summarising his portrait sketching process, de Sainson later recalled: “What I was doing caused a lot of laughter; every minute they tried to escape me.” (Kā Honoka, 18 December 2015 – 28 August 2016)

Collection

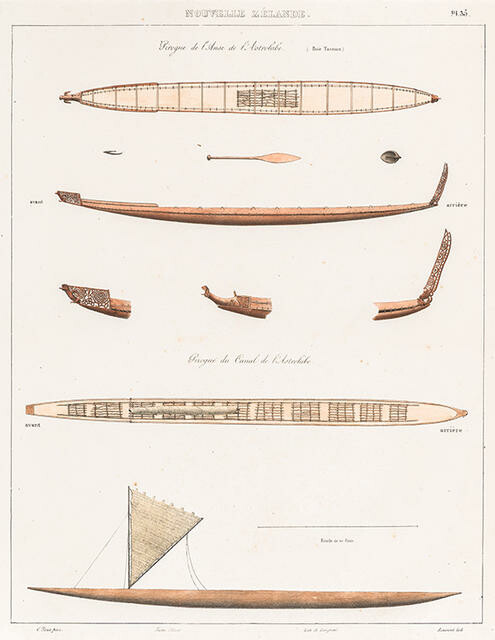

François-Edmond Pâris, Pierre Langlumé, Jean-Antoine Laurent, Joseph Tastu Nouvelle Zélande. Pirogue de L'Anse de l'Astrolabe. (Baie Tasman.), Pirogue du Canal de l'Astrolabe. Pl. 35

Aged just twenty when he joined Dumont d’Urville’s 1826–29 Pacific survey, François-Edmond Pâris created a comprehensive visual record of ships and boats encountered. In 1827 he recorded vessels he saw at Ūawa Tolaga Bay and Paepae-o-Tū Bream Bay, and Te Tai-o-Aorere Tasman Bay and Tāmaki Strait, Auckland.

(Out of Time, 23 September 2023 – 28 April 2024)

Collection

Conrad Martens Sydney from the North Shore

Conrad Martens left England for Rio de Janeiro in 1833. By December had reached Montevideo, Uruguay, where he joined Captain FitzRoy and Charles Darwin on the HMS Beagle, becoming ship’s artist on a survey of South American coasts. In 1835, Martens settled in Sydney and became an admired landscape painter who also produced popular hand-coloured lithographs.

(Out of Time, 23 September 2023 – 28 April 2024)

Collection

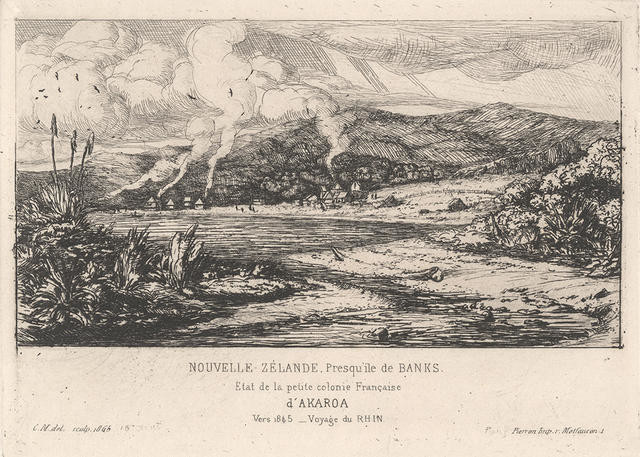

Charles Meryon Nouvelle-Zélande, Presqu’île de Banks. Etat de la petite colonie Française d’Akaroa. Vers 1845 - Voyage du Rhin.

Described as the father of modern etching, French naval officer Charles Meryon was one of the most important artists to work in Waitaha / Canterbury during the colonial era. He served on the Rhin, stationed at Akaroa between 1843 and 1846, to look out for the French settlement there. Meryon made numerous pencil studies at Akaroa which he later used as the basis for this series of etchings completed back in Paris during the 1860s. He planned to publish these and other images of the Pacific in an album, which unfortunately he never completed. The story of the French attempt to settle Te Waipounamu / the South Island is a fascinating chapter in New Zealand’s history. A French whaling captain, Jean Langlois, purchased 30,000 acres from Kāi Tahu on Horomaka / Banks Peninsula in 1838 and returned to France to get government support to establish a French colony at Akaroa. It was from here that he hoped the French would be able to expand throughout the rest of the South Island. A company was formed and sixty- three French and German settlers set sail on the Comte de Paris. They arrived at Akaroa in August 1840 only to find a Union Jack flying at Takapūneke / Green’s Point signalling that British sovereignty had already been claimed. Today, Akaroa continues to retain something of a French flavour.

(Pickaxes and shovels, 17 February – 5 August 2018)

Collection

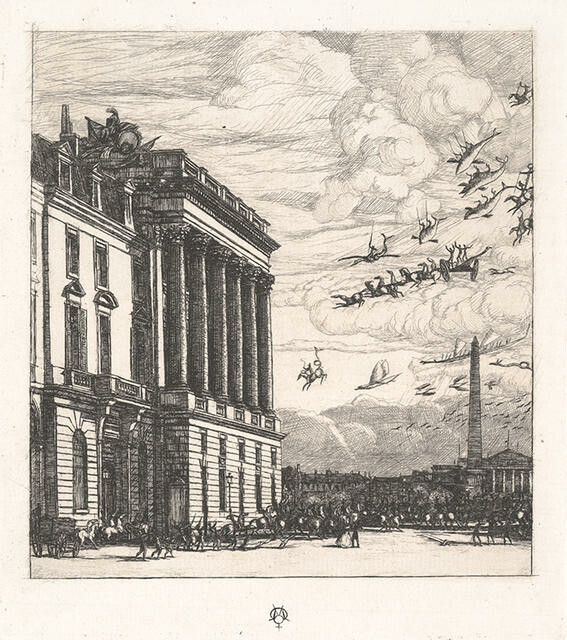

Charles Meryon Le Ministère de la Marine

Charles Meryon’s fantastical Parisian scene presents the French Admiralty building with a flying horde being delivered from the far ends of the globe. The crowd below is thrown into disarray as Roman charioteers, whales and whaleboats, a waka with sails, an anchor, serpents, cowboys and horses with fishtails prepare for landing.

Meryon’s impaired mental state in this period is the usual explanation given for this extraordinary etching. At the same time, it may be viewed as an image laden with personal symbolism as the confounding facts, fantasies and errors of the past make their perplexing return.

Meryon spent three years in Akaroa from 1843–46 as a young naval cadet, protecting the fledgling French settlement. Although this particular colonising plan did not succeed, the streetlamps of Paris were fed a regular supply of whale oil from Banks Peninsula in this period. For Meryon these were formative years and regularly revisited in his imagination. (Kā Honoka, 18 December 2015 – 28 August 2016)