Raising the Clay

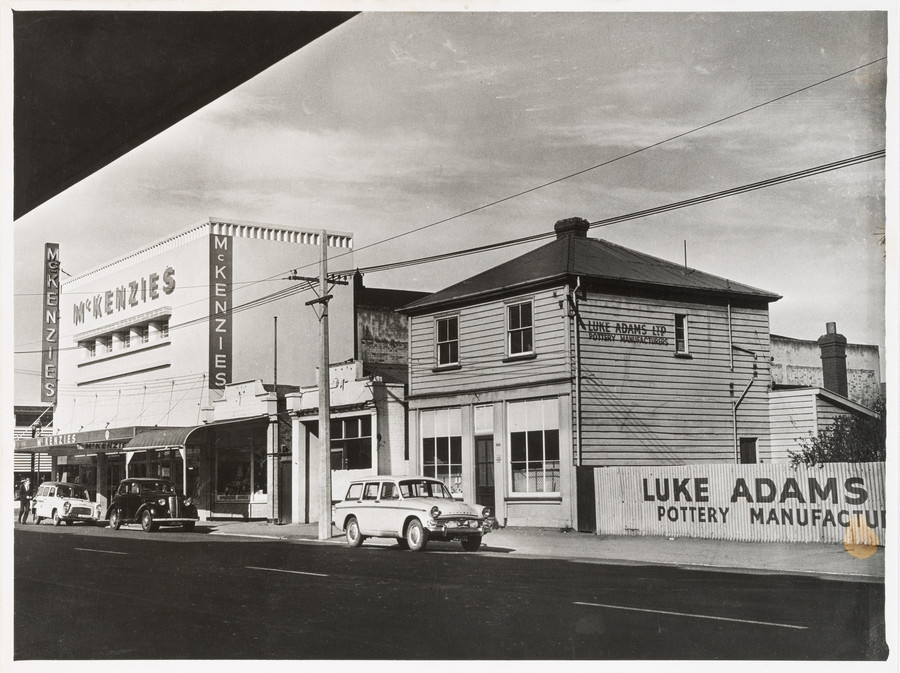

Ross MacKay Luke Adams Ltd., Pottery Manufacturers, Colombo Street, Christchurch c. 1965. Photograph. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archives

One of the themes explored in the Gallery’s new exhibition Leaving for Work is local industry, particularly in relation to pottery. The show includes an 1896 painting by Charles Kidson of well-known early Sydenham potter Luke Adams; three late nineteenth-century pots by Adams; and projections of a number of exceptional photographs by Steffano Webb. Keen to learn more, exhibition curator Ken Hall met up with local pottery historian Barry Hancox – perhaps best-known as former Smith’s Bookshop proprietor – and leading New Zealand photographer, Oxford-based Mark Adams. Mark’s links to this story include a distant family connection to Luke Adams; photographing many celebrated New Zealand potters of the 1970s and 1980s; and an abiding interest in land and memory.

Ken Hall: Barry, I’m quite taken with your collecting, the scholarship behind it, and the impact of it all together. The material is fascinating and beautiful. What are your plans for the research you’ve been doing?

Barry Hancox: Well, I’ve been collecting for a long time now – it’s over thirty years of accumulating Christchurch, Canterbury and North Canterbury industrial pottery, mostly from the nineteenth century. My ultimate objectives, especially now that I’m retired, are to document the collection properly and publish the full story. To that end, I’m bringing together documentary material of all kinds, and of course Papers Past is a great boon these days, to tell the whole story properly. Gail Henry’s books were pioneering,1 but skated over the top of this region to some extent, and it needs a more thorough treatment; particularly because what little evidence we had of this industry prior to the earthquakes has been so ruthlessly erased. I lost quite a bit of my collection, and I wouldn’t have been the only one, so it’s even more special in a way now because there’s less of it. I think it’s significant and the story needs to be told.

KH: Mark, I know your connection to potters and pottery isn’t the same as Barry’s but I see we’re going to find some links. For a start, you’ve got that family connection to Luke Adams. Can you tell us what you know about that?

Mark Adams: Nothing. [Laughs.] I was told by Dad that we were related, but I suspect it’s not in a direct line – he’s probably a second cousin. I’m also pretty sure that our lot, as opposed to Luke’s lot, came from ceramic producing districts in England. So my great- grandfather Adams was a carrier. He owned carts and a stables in Wainoni Road, and that would be the generation. But I’d actually like to find out what the connection is.

BH: Do you know which part of the UK he came from?

MA: No.

BH: Okay, because I’ve researched that and the original Luke Adams came from the South of England, near Southampton in Hampshire. He worked for a pottery business at a place called Havant, so when he arrived here he already had all the background and skills needed and he went to work for Austin & Kirk on Port Hills Road. That’s a bit different to what one might expect – that most who came with the necessary skills were from the well-known potteries district of Stoke in the Midlands, which was very industrial. But there was another tradition in Britain of much smaller regional potteries in country towns all over the place, producing ceramic goods in relatively small quantities for the local market. That’s Luke Adams’s background, which I think helps explain why he was never really comfortable working for somebody else, and I suspect that his ambition was always to have his own firm and to recreate here what he knew so well from his origin.

MA: And he had good clay nearby.

BH: Oh, yeah, the clay was available. But he also would have had a familiarity with a small craft semi-industrial set-up, different to the Wedgwood approach which was heavily industrial.

KH: So do you know that your branch of the family, Mark, came from the more obvious pottery districts? MA: No, but it was talked about. I remember Dad saying that they were from a pottery district but they didn’t say where. I’ve got a feeling that some of the family, on both Mum’s and Dad’s sides came from Hampshire, around Southampton.

BH: Yeah, that’s exactly right. On one of my visits to the UK I found myself in Havant, just inland fromSouthampton, looking at chimney pots… I noticed a distinctive regional style in which different coloured clays are combined to give a sort of streaked effect, and thought that was interesting because I’d seen it here. Not often, but I did come across chimney pots that had exactly the same treatment here in Canterbury; that can only have come here via someone like Luke Adams bringing his local tradition from the UK.

MA: There was a potter in Auckland called Jeff Scholes back in the seventies who did stuff using that mixed slate-coloured clay. I’m pretty sure it was Jeff...

BH: Quite a few people did it and they called it ‘Agateware’ because it looked superficially like cut agate. Adams didn’t do a lot of it, but there is this remote slight connection. So that’s it, there’s a craft pottery tradition that came here and a more industrial tradition that also came here.

![Charles Kidson The Potter [Luke Adams] 1896. Oil on canvas on board. Collection of Christchurch ArtGallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, gift of H. R. Adams, 1965](/media/cache/eb/d5/ebd5a3a5aeeccfe1c80a7c0972530606.jpg)

Charles Kidson The Potter [Luke Adams] 1896. Oil on canvas on board. Collection of Christchurch Art

Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, gift of H. R. Adams, 1965

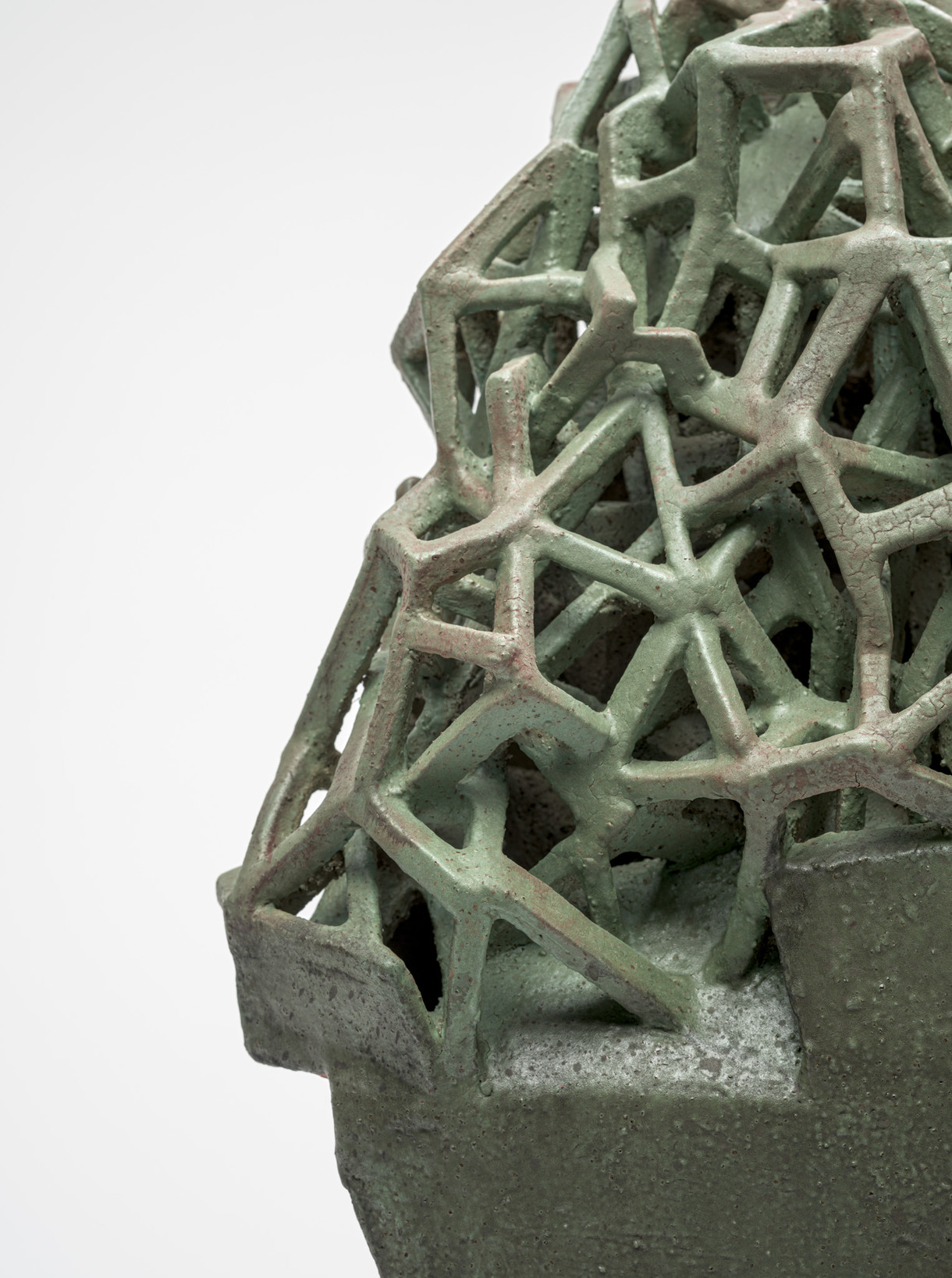

MA: And you were saying before that there’s a kind of a split between those guys and then the more self- conscious approach of the studio pottery movement which also came out of St Ives and Japan, Hamada. And that whole thing suddenly reared up here again in our generation, all my hippy mates…

BH: It reared up everywhere in the Western world. I think it was a kind of second-phase, in a way, of the Arts and Crafts idea and the revolt against industrialisation and the separation of people from a sort of basic connection with making…

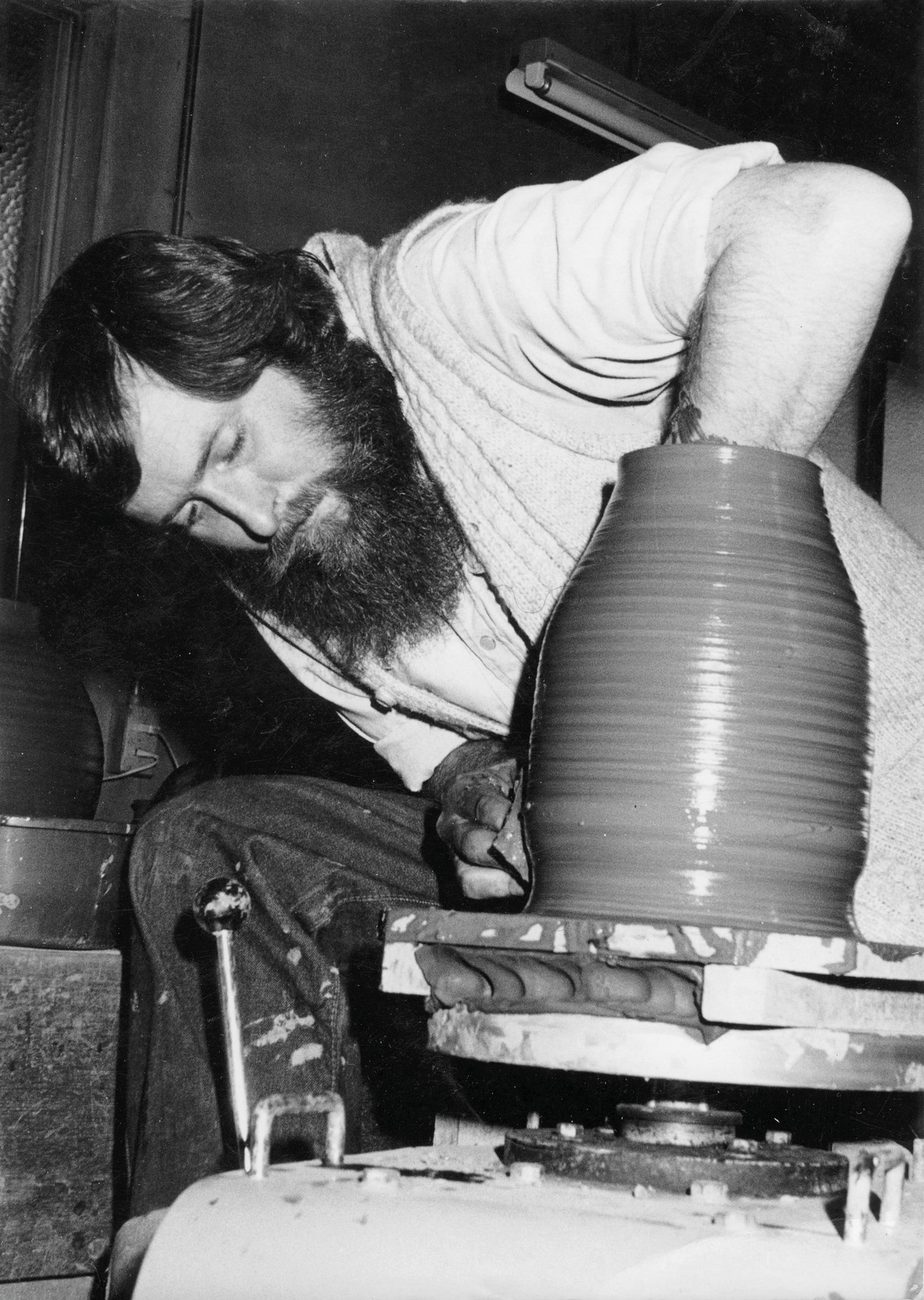

KH: I learned recently that the potter Yvonne Rust’s mother was Annie Buckhurst, who studied here at the School of Art and taught for several years from 1917. There seems a link here. Mark, you also mentioned living for several years from the mid-seventies near Whangarei, around some well-known potters. Some of your photographs are in Moyra Elliott and Damian Skinner’s Cone Ten Down: Studio Pottery in New Zealand. You took large-plate photographs of places, people, kilns being built, etc. (You and they were using technologies that would have been recognisable to nineteenth-century predecessors.)

MA: Yeah I did. I’m a plate camera photographer. But I didn’t – I went through the Art School here at Ilam in 1967 to 1970 – I didn’t meet Yvonne then but was aware of her through one of my mates who used to spend a lot of time at her place, and on the West Coast when she went there. I didn’t meet Yvonne until moving to Whangarei from Sydney in 1974, and then I took myself out there and met her. And from then on up until 1982 when I came down to Auckland, I did a series of photographs, on and off, because I was just really drawn to pottery, ceramics and the whole business of making it. I took quite a careful bunch of mostly 4 × 5 black and white sheets of film of all of the people around Yvonne that ended up further away in Auckland. There was a whole list of people, really.

BH: There were so many of them, it really did go from a few to many very quickly in the seventies and into the eighties, and then sort of fell away and now you don’t see it.

MA: Well everybody was very poor. No one was really making money; I mean, nobody had money but they were surviving. Up in Auckland, the Northland potters would cart carloads of pots down to Alicat – Pete Sinclair’s shop in Jervois Road, Ponsonby. They’d sell through there, and there were other places that I’m not really aware of.

BH: Yeah, but the interesting thing is that that’s a completely different rationale, in a way, to this. They were doing it for different reasons and in different ways, but still relying on the same technology. But they had to learn it. The tradition, which is what I refer to this as, had ended by then. And so the studio pottery movement of the post-war period was a new thing and different entirely to what was happening in the first hundred years.

KH: I came across a 1977 article in the New Zealand Potter about Luke Adams Pottery. It was interesting to see 1970s makers looking at this history. Mark, do you get a sense that the potters you knew were aware of the settler pottery tradition in any way?

MA: Yvonne certainly would have been. She would have known all about Luke. For the Northland people, possibly not, although Auckland had its own industries. The historian Dick Scott made a book called Fire on the Clay, about West Auckland. I did a bunch of photos for him and for that book in 1979, so became aware of that. I can’t speak authoritatively about New Zealand pottery, I’m a photographer, but it’s just that I happened to have had these interesting connections.

BH: Well, in a way, the discovery of the sort of settler pottery, as you called it, came along in the seventies and eighties too and that’s when people started to collect it. They had become aware of it in a way that they hadn’t previously and soon started to value it for its own sake.

KH: The writer of the 1977 article described going into Adams’s shop in Sydenham as a child with a school group. They were all making stuff and getting it fired there.

BH: I think that’s a connection, in a way. Luke Adams Pottery survived longer than most others and did sort of mark a transition, from what I call industrial pottery to craft pottery – facilitating the idea that kids could go and move around a lump of clay and glaze it and then have it fired in the kiln. Because, by the end, the market for what they were able to produce had disappeared, so they were looking around for ways to make money at a time when the trade was essentially over. There was a period when, I think partly because of his own background, Adams had this openness to the idea of pottery as a craft for everybody. They also made round terracotta plaques to sell to people who would then paint them, so they were selling for home craft activity long before they closed.

KH: I’d like to read out this Lyttelton Times account from the 1895 Christchurch Industrial Exhibition, which found Adams in “The Worker’s Department” at “his potter’s wheel skilfully [illustrating] one of the most ancient and widespread industries of the world.”2 Charles Kidson, who painted The Potter, was in the same exhibition in his role as assistant master at Canterbury College School of Art, showing unglazed pottery alongside Eleanor Gee and sculptor Charles Brassington. Their focus was the effective use of New Zealand fauna and flora in clay modelling design; the display included tiles, vases, an umbrella stand and “A tobacco jar, decorated by Mr Kidson with Native carving and two lifelike Maori heads... Mr Luke Adams of Sydenham has kindly assisted the school by throwing the vase forms to which the decoration has been applied.”³ I like seeing more of a connection between Kidson and Adams than what we see in the painting. Which, the more I look at, the more I see as a set-up. I mean, throwing flowerpots is not Luke Adams’s typical working day, is it? It’s more like a photo opportunity. He surely had other people doing this most of the time.

Arthur Bender Luke Adams Pottery, Sydenham c. 1930s. Oil on board. Barry Hancox Collection

BH: I should have brought this out first but here’s this little oil sketch, of the Luke Adams Pottery, by somebody called Arthur Bender. And you can see, I think, nostalgia for something that was disappearing is already evident in this painting. This is another manifestation of that.

KH: I think you’re right. There’s quite a respect going on there, isn’t there? And it does relate to the Arts and Crafts thing that Kidson was all over.

MA: These kiln shapes [in the painting]: I went to Corbridge – an old Roman fortress town right up on the border out of Newcastle upon Tyne – where Mum’s father and grandfather came from and there were these big [structures like this] just outside of town, two or three of them.

BH: They’re bottle kilns, which I’ve also seen along the canals that used to service the potteries in the Stoke-on-Trent area. You would move the clay and manufactured ware on the water because it was heavy and it was easier. Because nobody was looking at that, the kilns that were demolished elsewhere survived there, so those bottle kilns are now, of course, listed buildings and protected. I don’t know of a single example that survived here in New Zealand. There were also earlier ones in Christchurch – nothing to do with Luke Adams – out at Ford and Ogden’s Pottery and at Homebush as well, but none have survived.

KH: Homebush was at Glentunnel, and was big?

BH: It was an industrial site, so yes, it was substantial. There were also Hoffman kilns which don’t look like these at all. They were downdraft kilns with a big central chimney, and there were several of those around here on the Port Hills Road. Luke Adams didn’t have one because it was too big, but they had them out in mid-Canterbury and down in Ashburton and so on. Another was Thomas Hills’ brickworks in Rangiora; again, not a single survivor. There’s a kiln left at Benhar [North Otago] that only survived because when somebody turned up to dismantle it the locals intervened and prevented it happening. But the careless disregard for the architectural evidence of industrial history in New Zealand means that nothing survives, nothing. Drive around Christchurch now there’s no evidence at all that there was ever any local pottery industry.

KH: Do you know where they all were?

BH: Yeah, the earliest sort of pottery was when they were making bricks for chimneys in the 1850s, and they just used clamps. But the first pottery was established on the corner of Barbados Street and Ferry Road where the Catholic Cathedral site is. There was a Hoffman kiln and bottle kiln and the rest of it, drying shed and everything, in the 1860s. Nothing survives there now at all and as far as I’m aware no drawings or photographs were ever made of it.

KH: They were making bricks and presumably chimneys and drainpipes?

BH: Bricks, pipes – pipes were the big thing.

KH: Especially in a swamp, right?

BH: Yes, and terracotta tiles were in great demand because kitchens and dairies were all floored with terracotta tiles laid straight on the earth, so there was a big demand. And they survived. I’ve got a few – including one from this original pottery that we’re talking about.

KH: So did pottery also arrive as ballast? And was there a demand unable to be met by local supply?

BH: Not really. The industry arose to supply domestic wares of cheap low-grade character. What was coming on the ships was porcelain and bone china. That’s what everybody wanted. Nobody wanted to eat off what was being made in Christchurch; they wanted bone china from Staffordshire. But for kitchen stuff and storage stuff and stuff that you’d use on the farm and stuff to move liquid around and so on, no, that wasn’t being imported – it was made here.

KH: People needed a lot of pottery.

BH: For sure. Glass was expensive at the time. I mean, a glass vessel in 1870 cost more than an equivalent in clay. So pottery was the cheap material of commerce and needed in half-, one- and two-gallon demijohns. That’s how you moved liquids around and sold them. It all had to be made here because it wasn’t economically practical to import. And then all of the early potteries vied with each other to get provincial government contracts to supply pipes, and imported pipe-making machinery from the UK and set it up, making pipes by the mile, literally; glazed pipes for domestic sewerage installations in the city and unglazed ones for agricultural drainage projects.

MA: Sewerage and storm-water pipes.

BH: Yeah, so the lion’s share of the trade was bricks, pipes, tiles, and then the domestic stuff was a kind of sidebar from that. And apart from Adams, who didn’t make bricks and pipes, all of the rest of them made those as their primary production, and the domestic wares were of secondary importance.

KH: Back to the painting briefly – The Potter – it’s not exactly a portrait. It was first shown at the Canterbury Society of Arts in 1896, and described by a reviewer as: “A large canvas which, though not a portrait picture, bears an admirable likeness to a well-known Christchurch tradesman at work at his wheel.” Barry, how had he made himself so well-known?

BH: Tradesman, I think that’s a good description. He produced the kind of things that people wanted, and he was quite active socially so very accessible. Where his pottery was in Sydenham was reachable, and was the sort of place that people could observe. It wasn’t too big. And what he made was available in the shop next door so the buyer went to the source. All of that contributed to this sense of familiarity that people had with Adams, which they didn’t with the other active potteries.

KH: It’s also always fascinating watching a potter at work. He put in these industrial exhibitions and no doubt mesmerised visitors. You might be able to comment on this, Mark – I mean, you’ve seen a lot of this.

MA: Oh, it’s great to watch; and, of course, the firing end of it is all very convivial, sitting outside as the dusk comes down, drinking red wine.

BH: The craft potters were using gas-fired kilns though, weren’t they, or even wood-fired kilns?

MA: Well, most of the guys up North were using diesel. It was Barry Brickell who helped Yvonne build her kiln. But I don’t know who started it or who made the first diesel-fired kiln. Was it Brickell?

BH: I suspect that that was something that they learnt from somewhere else... But, of course, Adams was very much in the nineteenth-century carboniferous capitalist style – I mean, everything he did was coal fired and the same with Austin & Kirk around here and in mid-Canterbury. So when the kilns were being fired there was thick heavy smoke hanging over everything; it took a couple of days to reach firing temperature and a couple more days to cool down again before the kiln could be unpacked. Meanwhile, around here on the Port Hills Road, one kiln would be being packed whilst one was being burned, so it was more or less a continuous process. Thick smoke on a frosty winter morning, and copious quantities of coal.

KH: It was pretty disgusting, wasn’t it?

Steffano Webb Reece Brothers' firm, Christchurch. Collection of negatives. Ref: 1/1-005102-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

BH: It was definitely a very dirty industry. And then, of course, there was all the waste, the broken shards, the waste from the pugging process. You see it in the Arthur Bender painting – piles of slag and ash and stuff. It was a very dirty business. I’ve often thought about what it must have been like for, say, a seventeen- year-old school leaver who got a job at the pottery. He’s starting work at 7am on the Port Hills in the winter; he’s in the workshop there and he’s got his hands in this cold, wet clay and is making pots, one every two minutes. And he’s yearning for a smoko but can’t stop till 10 o’clock, and even then it’s only five minutes. These people worked hard. It was physically demanding too. Imagine doing 100 pots in a couple of hours, the strength you’d need in your fingers and your upper arms. I mean, you had to be physically fit. One of the things I love about the kind of pottery that I collect, this industrial pottery, is the evidence of that firing process; there are blemishes, there are patches in the kiln where whoever was responsible for it that day wasn’t paying enough attention and it didn’t get quite hot enough so it affected the way the glaze behaved, and then there were impurities in the coal that affected the glazes, all of that. It wasn’t a precise and exact science at all, and it was more important to burn the bricks and get them done because the demand was there all the time. Whereas the craft potters had the luxury of doing everything on a smaller scale and being able to use a more modern approach, which meant that those impurities and imperfections never occurred. If something came out of the kiln at the end that wasn’t quite right then they would dispose of it and start again because that was how they were; whereas the industrial potters would have just marked it down in price and sold it anyway.

Ken Hall spoke to Barry Hancox and Mark Adams in September 2021.