As Stark and Grey as Stalin's Uniform

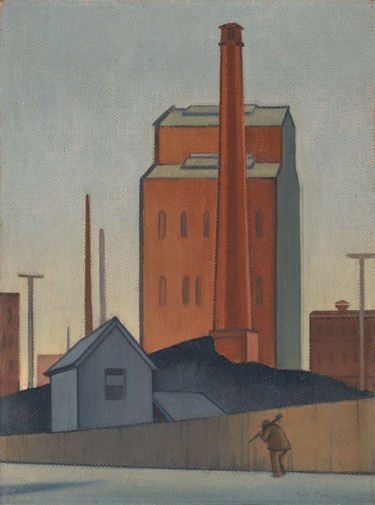

Heading along to the stunning Rita Angus: Life & Vision survey exhibition at the Gallery in 2009 I always had this nagging feeling that one work was missing from the walls – Angus’s Gasworks from 1933. This painting was one that I knew only through the black and white image that appeared first in a volume of Art in New Zealand in 1933; the same reproduction that was later used in Jill Trevelyan’s excellent biography of Angus and also in the catalogue for the National Art Gallery’s 1982 retrospective, Rita Angus. For the New Zealand art historian, Gasworks was a kind of legend – painted by one of the country’s best artists yet seen in person by only a very few. In 1975, when Gordon H. Brown curated New Zealand Painting 1920–1940: Adaption and Nationalism, Gasworks was listed as ‘location unknown’ in the accompanying catalogue. Amazingly the painting was also not included in the retrospective exhibition of 1982. We had grown to know this painting purely through a grainy black and white illustration from 1933. But the painting was never lost – Gasworks is a painting that has been cherished, protected and loved by the same Christchurch family since the early 1940s. And now, having been placed on loan to Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, it is available for the public to view for the first time since 1933, when it was shown at the Canterbury Society of Arts.

Seeing Gasworks in person last year as it leant against a couch on the floor of a suburban Christchurch house sent shivers down my spine. I know that sounds corny but it really did give me goosebumps. It glowed in the winter light and – I am an unabashed fan of Angus’s painting – filled me with joy. It is a tough little painting, not very big at all. There are no trees or grass visible, just the gritty, in-your-face view of one of Christchurch’s most industrialised sites. A lone figure walks beside a long fence-line in Falsgrave Street, Waltham; he is completely dominated by the chimney, a large pile of coal and the Retort House of the Christchurch Gasworks. He’s a worker in the real sense, bent over by the weight of a long heavy pole, possibly a pinch bar, as he slogs his way down the street and the sun makes its slow appearance on the day.

Of course Rita wasn’t the first to paint industrialised scenes in New Zealand. A year earlier Christopher Perkins had exhibited his famous painting Silverstream Brickworks (1930, work destroyed) at the 1932 Group Show, while Rose Zeller also painted industrial sites and Robert Field had painted Melbourne’s Gasworks in 1933. Painting industrialised landscapes was not new but what is striking about Angus’s work is the fact that any sign of nature has been completely obliterated by the grimy buildings of the Gasworks. It must have been one of the ugliest views in Christchurch at the time yet it was one that she, perhaps from a socialist perspective, held up as worthy of painting – the humble worker celebrated for a brief moment as he goes about his day.

When it was shown for the first time at the Canterbury Society of Arts Annual Exhibition in April 1933 the work stood out, not only for the way Angus had reduced the architectural shapes to simplified, balanced forms, but also for its “austerity and dignity”.1 It was reproduced in the Press and later in Art in New Zealand and had an impact on many. The painter Margaret Anderson later recalled “the tall chimney of this work as an event of greater artistic importance than any that had happened in Christchurch for years”.2 In Dunedin Doris Lusk and Anne Hamblett were also impressed by Gasworks (which they presumably saw in Art in New Zealand) as a rare example of modern art; Lusk later painted the Dunedin Gasworks in a 1935 work titled Gasworks and Foreshore, Dunedin.3 Lusk was to continue painting industrial sites throughout her career, most famously The Pumping Station (1958) held in Auckland Art Gallery’s collection.

In 1933 the Christchurch Gasworks would have dominated Rita’s life as indeed it probably did many Cantabrians. It was a site she would have seen on a daily basis. She had married fellow painter Alfred Cook in 1930 and the pair lodged with Alfred’s mother and his brother James at the Cook family home at 120 Ferry Road, no more than a block from the Gasworks. In January 1933, Rita’s sister Jean also began boarding with them. The tall chimney, buildings and gas holders would have been visible from the backyard of their home. The site had been cleared by the time I arrived in Christchurch in 1988 but my friends who grew up in the city during the 1970s all speak of it as a sight to behold and one that dominated the city.

In 1976 the poet Denis Glover reminisced about Angus and the Gasworks painting, providing an interesting context for the work and the general mood at the time it was painted.

The first time I even heard of Rita was when I saw Gasworks. I was young and more ignorant than I am now, if that were possible. Most of us students were in a mood of fierce idealistic realism. The Woolston Gas Works was as stark and grey as Stalin’s uniform. Location: next to the Roman Catholic cathedral which Bernard Shaw affected greatly to admire – one suspects to pull the Anglican leg about their quaint little period piece now peered down on in the square by so many more impressive cinemas, banks, and insurance buildings. Of course the Anglicans actually gave that site to “the Italian missionaries in Barbadoes street”.

If it were only on a hill, the Roman Catholic Cathedral would appear as a noble baroque cameo in the St Peter’s style, and no doubt it has been well or ill portrayed by many of the faith. But the Gas Works next door – here was something! In one puff was blown away all the genteel piddle-painting English, to this day not sure if they are New Zealanders or First Four Colonels’ Daughters.

No that’s not fair and no longer true. At that time I could sit in rapt contemplation of a power pole as a reaction against bloody Corot trees, roses roses round the door, and West Coast bush bush bush with mum walking down the road followed by a tired horse to give proportion to the height of those dull trees.

Richard Wallwork would paint Greek grottos and temples, highly eighteenth century fake, and Sydney Thompson would repair to France to sell New Zealand landscapes returning to sell culture-vultures pictures of fishing-boats in Concaneau or some probable place.

Give me the Gas Works. I remember Rex Fairburn saying, when I drove him over a sunset Porters Pass, “These are great crouching tigers! Why does your Canterbury School make them look like Sunday ice cream?”

And that point brings me back to Rita, because she would have none of the delirious woofy mango-swamp muck of the then Auckland School. She set out to impose order and clarity and immense discipline on what she saw. There were no emotional overtones. The looker could provide them for himself.4

So now, eighty-five years since it was last on public display, we are delighted to be able to include Gasworks in the exhibition Waiting for a Train: New Zealand Modernist Landscapes, where it sits in close proximity with two other important Angus paintings, Cass and Mountain biological station, Cass.