The Borrowings of Francis Upritchard

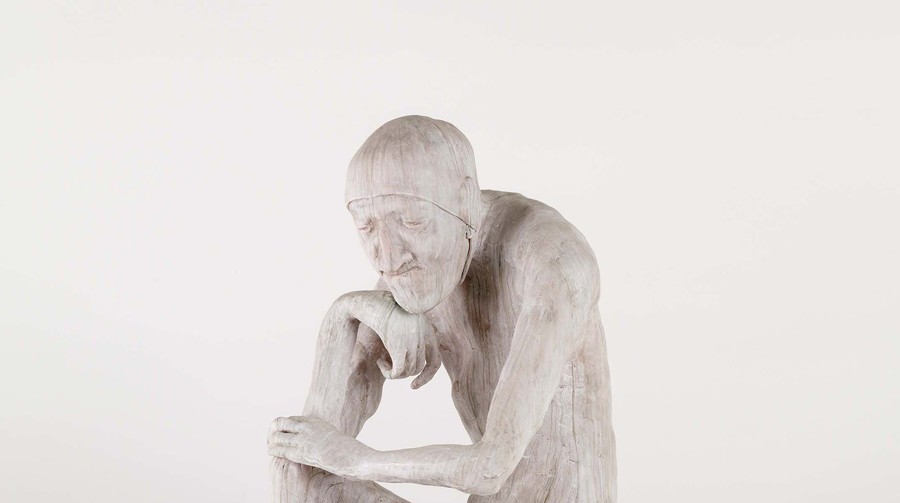

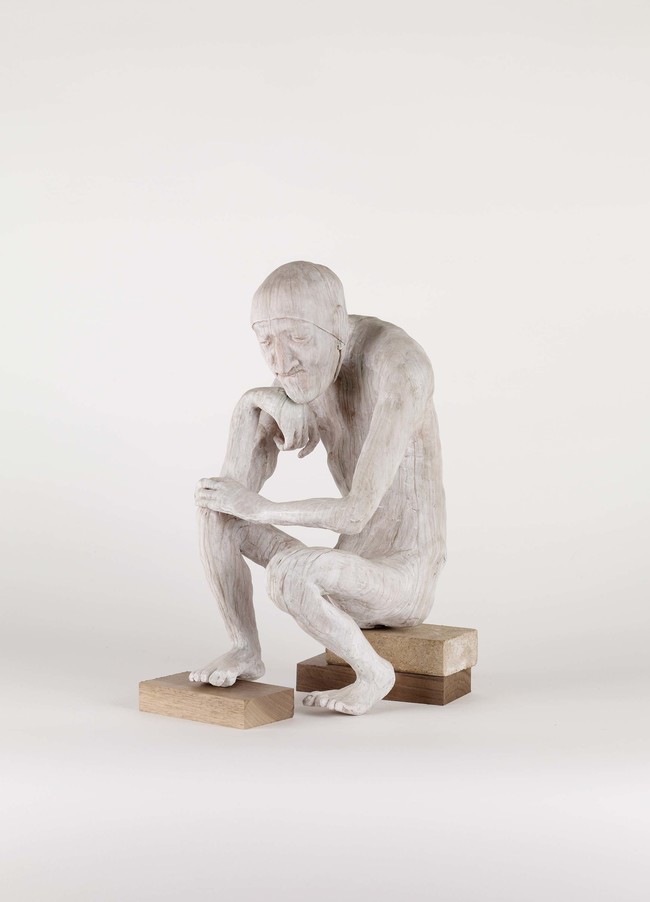

Francis Upritchard The Thinker (from Unmoving) (detail) 2007. Modelling material, foil, wire, paint. Courtesy Kate MacGarry, London

Arriving at the studio and home of Francis Upritchard on a Tuesday morning in East London, you’d hardly know she was opening a solo booth at Frieze Art Fair later that day, launching a fashion collaboration with Peter Pilotto the following day, and juggling studio visits and interviews throughout London’s hectic art-focused week. She’s the picture of tranquillity. The calm doesn’t last long though, as discussions of Christchurch’s rebuild, the Christchurch Art Gallery, our friends and memories are quickly interrupted by an escalating flurry of visitors and family dropping by and couriers collecting objects, packing crates, dropping off documents.

I’ve lost track of who lives there and who is arriving to work, but it’s a division that I sense Upritchard also pays little heed to: she surrounds herself with creative people; collaborating formally, or sharing ideas, materials and techniques informally. Many of the fabrics and materials you’ll see in her sculptures have come to her via friends and family – others she’s commissioned from artisan weavers. And she is also a ‘borrower’, like some of the more culturally critical attitudes of her objects. Her borrowing comes through travel – she picks up skills or discovers artefacts and forms as she moves around, and will stay for extended periods of time on residencies in order to learn the techniques she’s hoping to master.

Tessa Giblin: When you are adopting objects from other cultures, or learning their craft techniques, how do you relate to the historical context of these forms?

Francis Upritchard: I love stories and mythology. When I first started working in the Amazon jungle (during a 2004 residency in Belem, Brazil), the guy I was working with told me all about his creatures and what they mean. One of them was a mythological creature – a guy with his feet turned backwards, who’s holding a goat. You’d see him and shout, ‘Hey, my goat!’ and he’d surprise you by running off in the opposite direction. He also made a lot of dolphins. Apparently the dolphin symbolises another mythological creature – a man who could turn into a dolphin, then go and have sex with all the women on a little island and swim off again. And there was another, a monkey with one eye, and, well, loads of different local mythologies. I guess I find these ideas a little more interesting than religion.

TG: How did you find yourself working in the Amazon, working with rubber from trees?

FU: I was trying to make my work as I usually did, using found objects. But during that trip to Brazil, I couldn’t find any spare objects because everyone there uses everything. I went to a craft fair, met my friend, a local artisan named Mr Darlindo, and just fell in love with his work. I asked if I could pay him to teach me. So I went out to his amazing place on the edge of town and he showed me how he made his work. Even now I buy material from him. He supplies me with balata – raw, untreated rubber straight from the tree. I heat it in a bath of nearly boiling water, and it becomes very hot and malleable, and then I sculpt it in a bath of cold water. So the works are made, pretty much, underwater. I’ve got about twenty minutes, because it’s heating and cooling simultaneously. I’m basically burning my hands by putting them in hot water, then soaking them underwater for twenty minutes – it’s a nightmare on the hands, but it’s also extremely fun. It is an ancient technique that people have been using for centuries. More recently balata was also used industrially inside old-fashioned golf balls, and it used to be used for underwater cabling.

TG: And what creates the variation in colour?

FU: The darker brown is older balata, and the lighter brown is newer, better quality. Before he sends it to me, my friend heats it a few times to get some of the bark out, so it’ll be slightly cleaner and have hopefully a few less insects.

TG: Have there been other times in which you’ve studied with artisans from different fields?

FU: Yes, a lot. There’s a big pottery vessel that I made with Nicholas Brandon, who’s a potter I’ve known since I was a child. He’s from that generation who are digging their own clay, making their own glazes, doing completely wood-fired work – both bisque and second firing. I work with him a lot, and I’ve worked with other potters over the years. It’s because pottery is really ancient as well. I first started learning at Camden Arts Centre, but I could never get the glazes or the feel I wanted. I realised it was because I was using this pretty much dead technique of firing in an electric kiln. It’s not alive. I think Nick does it over eighteen hours with bisque firing and fourteen hours for the other firing. So it’s very long, technical and precise, but it’s mostly to add depth and irregularities to the glazes.

TG: Do you think about materials as things that hold meaning, associations or contexts that you want an artwork to become laden with?

FU: Sort of, but not like ‘this is cotton, cotton means this’. It’s more about something I pick up and I feel really drawn to. Lots of works at the moment contain charms that I have collected over many years. Even though I don’t believe in luck, I have a sentimental attachment to the charms or to certain fabrics and things. I really love fabrics – they’re important to me because they’re beautiful, and they are worn. Whether you like fashion or not, every kind of cloth you put on your body is a choice and can be read.

TG: You often seem to work with quite rough, imperfect fabrics; fabrics where you can feel the particular fibres within them. You don’t seem to favour machine-made fabrics.

FU: I use many good quality fabrics that are maybe hand-woven rather than machine-woven. The most recent Japanese ones are just very sophisticated loom-woven. But at the moment, I’m using a lot of nylon (like tights) and printed fabrics as well. It really is a huge range: hand-woven and painted bespoke for me; a silk scarf from a second-hand store; generic wool; high-quality wool; cheap linen; funny tights; and cheap acrylic. They’re all different – one figure wears muslin I dyed myself, another wears a T-shirt that I owned. So, you know, lots of them have quite personal stories. One of the shawls, my weaver friend gave to me, and her brother had given it to her. The accumulation of stories is nice. Fabric from an old skirt of mine. The piece of trimming that I have been carrying around for years – I’ve still got some of it left. An old blanket of Martino’s. An old blanket I found in New Plymouth. Hand-painted trousers copying a curtain that I have at home. Fabric that my neighbour made for the clothing brand Acne, with a Mexican jeans patch ironed on. Lots of different times and types of things jammed together. There’s even some fabric my sister Hannah bought for me, and I thought – that’s disgusting, what on earth will I use that for? But I kept it because every fabric she ever gives me ends up in my work. I’m not trying to make pretty things; I’m trying to make things that are interesting.

TG: You say that you don’t want to make pretty things, but you want to make interesting things. How could you describe what that means to you?

FU: I’ve always found figurative sculpture to be really problematic. I’d been making this animalistic sculpture for many years, and around 2007 I decided not to make any more shows for a year. I just worked on my figurative art to see how that developed. Later on I went back and I realised that of course the Pākehā shrunken heads are figurative art, and that the mummy is figurative, but I’d never seen them that way. When I made The Thinker (2007), I was looking at carved, medieval German work. I felt like the pieces I was making were very old-fashioned and the most obvious way to take them out of this old-fashioned feeling was to add colour. I was doing this faux-bone look – scraping them, scoring them. It’s very much in the vein of Rodin’s Thinker, sort of gone-wrong as if it was mated with a medieval sculpture. Also I wanted it to look like a bit of a doofus.

Francis Upritchard The Thinker (from Unmoving) 2007. Modelling material, foil, wire, paint. Courtesy Kate MacGarry, London

TG: The sculpting of faces is such a curious thing, isn’t it, because they’re so sacred to so many people. How do you think about those complications or those sensitivities, especially when looking at or borrowing from different cultures?

FU: Well, they’re so different. The Pākehā heads (like Sammuel Horwell, 2015) have a really different meaning politically than these other sculpted faces. The Pākehā heads are really specifically about the situation in New Zealand. We all know about the very problematic historical trade of Māori heads, so for me this was like feeding back to the aggressor, like you’re buying back your cousin who was up to no good. I directly work with Māori and Pacific treasure – for example, the works that I call ancestral boxes. They’re very inaccurate – decorative rather than spiritual. They’re meaningless, rather than full of the power of real taonga, and they have no mana. They’re plastic rather than bone – they’re really bereft of anything, apart from showing how very special the real thing is.

TG: Even in your own personal narrative?

FU: Especially in my personal narrative. And so they’re more about memory; they’re all made here, in Britain, not looking at Māori work but remembering it, and remembering it obviously incorrectly. Also I’m trying to force these shapes into the voids left in compass boxes, so that gives it another, sort of, fucked-up-ness. That’s the shape of a compass and I’m trying to make some sort of tiki-ish thing in that hole, so not only is my memory incorrect, but the whole shape of it is never going to work, so it’s quadrupley wrong. Around the time I’d started making these works, I’d gone to visit the Wellcome Trust in London and saw a whole load of tikis that were really incorrect, which were made by sailors on the way back from New Zealand in the nineteenth century, appropriating and borrowing from their travels in the South Pacific. That’s when I started making the heads and the misremembered tikis. They’re made of this plastic, which is basically a poisonous material, rather than a natural bone. And they’re made by modelling rather than carving, which is taking away something – building rather than removing. You know, I’m not religious, and I think all my things are specifically non-spiritual. The figures are all about the look of the figure, they’re nothing to do with inner life.

TG: You also seem to have quite a tender relationship with literature. Time and again we’ll see catalogues and artists’ books about your work populated with pieces of fiction you have commissioned.

FU: Yes, I read a lot of New Zealand literature when I was young. Maurice Gee, Margaret Mahy, Witi Ihimaera, Owen Marshall. But Gee was actually my favourite. I loved those strange stories from O.

TG: And so when you commission works of fiction for your books, what do you say to authors?

FU: I just say, ‘Look at the work and do what you want.’ Keep it short. Have fun. Do it fast. The texts are commissioned to talk alongside my work. Not necessarily about it, but often there are characters or components that relate directly to my work, that have been really important to me. The last one, done for the Jealous Saboteurs book, is by Deborah Levy. She is a fantastic writer. I’d just read her book Swimming Home, which I adored, as well as her earlier novels, and a really lovely feminist text called Things I Don’t Want to Know, which is a rebuttal to George Orwell’s Why I Write. It’s a bit like Virginia Woolf ’s A Room of One’s Own, it’s super good. She was born in South Africa. Her father was anti-apartheid and was jailed, and the family politics are very present in her earlier works, which are set in South Africa. So I thought that she would really understand my New Zealand past, and write about it interestingly. The story she wrote isn’t actually about that much at all, but she touches on things that are current and relevant, like fleeing from war. It’s really beautiful, it’s actually about that sculpture I talked about earlier, The Thinker: she’s written a text about what The Thinker might be thinking.

TG: When you leave your home, as you and I have done, your reflection on it and its place in another world comes into focus in quite a sharp and surprising way. I remember becoming profoundly aware of the extraordinary historical self-determination of women within New Zealand – something I’d always known about, but it was in the telling of the story of Kate Sheppard and her fellow suffragettes to others, that it really began to impact on me.

FU: That’s something I thought about a lot when making this exhibition – what changes when you leave. The exposure I had to different forms affected me a lot – from Rome to Japan, Brazil to London, absorbing the sculptures, architecture and crafts everywhere I went – and I think also emboldened me to reflect on the New Zealand cultural complexities in a potentially freer way, with a self-deprecating idea of how the modelling or making of something transforms the memory of what it actually was in the first place.

Tessa Giblin spoke to Francis Upritchard in October 2016. Interview with with thanks to Henrietta Edgar. Francis Upritchard: Jealous Saboteurs is presented as an exhibition partnership between City Gallery Wellington and Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne and supported by City Gallery Wellington Foundation.

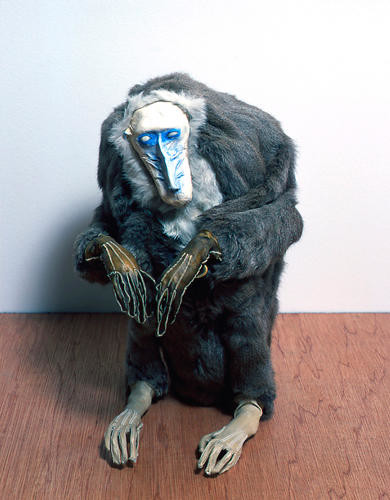

Francis Upritchard Sammuel Horwell 2015. Foam, nylon, fake hair and teeth, resin, glue. Courtesy Kate MacGarry, London