Colin McCahon: Five Years in Christchurch, 1948–53

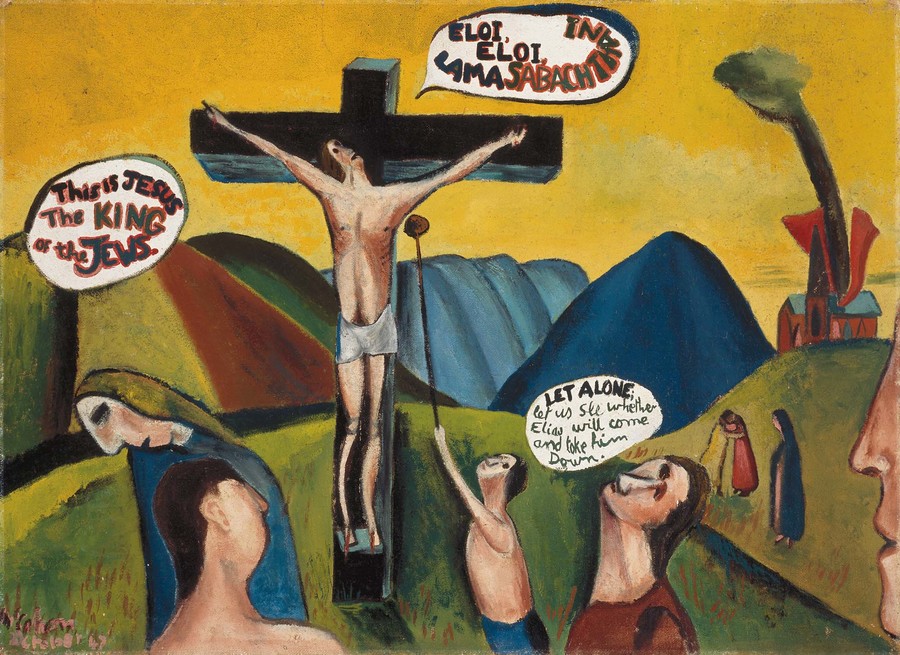

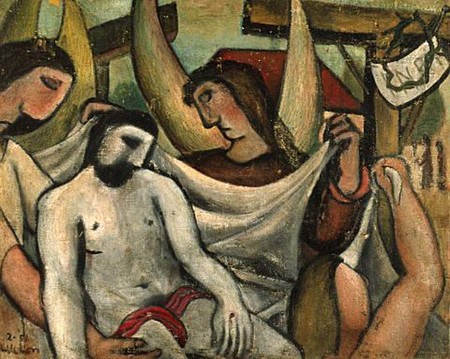

Colin McCahon Crucifixion according to St Mark 1947. Oil on canvas on board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by Colin McCahon on the death of Ron O'Reilly, 1982

Prior to moving to Christchurch in March 1948, Colin McCahon and his family spent a little over a year living in Muritai Street, Tahunanui, on the outskirts of Nelson city. It was his most productive period as a painter to date – a phase dominated by figurative paintings with some landscapes. The products of this prolific period were brought together in his first major one-person show, at Wellington Public Library in February 1948, organised by his Dunedin friend, Ron O’Reilly. An exhibition of forty-two works made between 1939 to 1948, more than half produced in 1947, it consisted of roughly equal numbers of landscapes (including Otago Peninsula and Maitai Valley), biblical paintings (King of the Jews, Crucifixion according to St Mark ), and non-biblical figurative works (A candle in a dark room, The Family). Although it was reviewed favourably in The Listener by J.C. Beaglehole, the subsequent letters column ran hot with controversy, and it brought McCahon to national attention.1

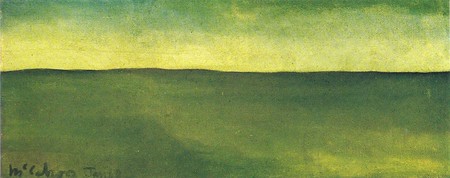

Colin McCahon The green plain 1948. Oil on canvas. Private collection

Why, then, just weeks after this ground-breaking show, did the McCahons leave Nelson and move to Christchurch? It was not a planned, or even a willing move, but one that was forced on them by circumstance. The sad truth is that their landlord wanted them out of the Muritai Street house and they could find nothing else suitable in the area. A letter to McCahon’s friend, Charles Brasch, responding to Brasch’s suggestion that he might visit them in Nelson, indicates that they were willing to move anywhere they could find an affordable dwelling:

And goodness knows where we’re going to. There is nothing here. So we hope to find something – rather hopefully – around Wellington – Hutt Valley, the landscape from Petone is excellent but have heard of nothing definite yet.

Failing that we thought of Cromwell or Alexandra – do you know of anyone there who could help by sending us news of empty houses – we can live in most slum like conditions if necessary.2

A month later they were gone from Nelson, staying temporarily with family in Dunedin and still without firm plans. It was eventually decided that Anne and the children (there were three by this stage, a fourth came later) would stay in Dunedin with her parents – her father was an Anglican minister – while Colin looked for something permanent in Christchurch. In the event it was more than a year before he found a place where they could join him. In the meantime he boarded with his friend Doris Lusk and her husband, Dermot Holland, at 52 Hewitts Road, Merivale, using a converted wash-house at the back of their house as a bedroom-studio.

It is possible that Christchurch appealed to McCahon as the home of the Group, with which he had first exhibited (as a 21-year-old) in 1940, and again in 1943, 1946 and 1947 (there were no Group Shows in 1941, 1942, and 1944). The leading members of the Group at that stage were Eve Page, Rita Angus, Olivia Spencer Bower, Leo Bensemann and Lusk, all of whom lived in Christchurch; Toss Woollaston, though living in Mapua, was also a regular contributor.3 Thus, McCahon’s work was already known and appreciated by at least some people in Christchurch, and this may have been a factor in his moving there.

Empty houses, however, were hard to come by, and the Hewitts Road arrangement lasted for more than a year. We get a couple of glimpses of McCahon in residence there. John Caselberg, a young writer who had been studying in Dunedin, was taken to meet him. He later recalled: ‘In Christchurch, James K. Baxter took me one morning to meet [McCahon]. In his studio workshop at Doris and Dermott Holland’s, he paused – looked up from his work – making jewellery4 or preparing paintings – and after a handshake greeting, asked, perhaps unconsciously describing himself: “Who are you? A poet or prophet or what?”’5 Another glimpse comes from Charles Brasch’s 1949 journal: ‘After lunch we went to see Colin McCahon, who is still living at the Hollands’ – Doris Lusk’s; Colin stopped painting when we arrived – exhausted, trembling & very hungry, depressed because a big Crucifixion he has been working on for a long time will not go right.’ 6

In the fifteen months or so that McCahon spent at Hewitts Road he painted some of his most famous works including The green plain, Hail Mary, Takaka: night and day and The Virgin compared. In his 1972 Survey essay McCahon wrote:

A lot of painting dates from the Christchurch years. [Takaka: night and day and The green plain] were painted in my bedroom-studio at the Holland’s place. The Takaka painting was painted round a corner of the room, no one wall being itself long enough. Once more it states my interest in landscape as a symbol of place and also of the human condition. It is not so much a portrait of a place as such but is a memory of a time and an experience of a particular place.7

As the date on the painting indicates, The green plain was started in January 1948, before he moved to Christchurch, but was finished at Hewitts Road.

At Hewitts Road there was no sudden change of direction in McCahon’s work; he continued producing both landscape paintings and figurative religious paintings in almost equal numbers, as before, though there were fewer of the third category of works produced in Nelson – non-religious figurative paintings. It is interesting to note that of the landscape paintings made in his first year in Christchurch, only two, Taylor’s Mistake8 and The green plain make reference to the Canterbury environment. It was not until late 1949 that McCahon produced further images of Canterbury (apart from some Conté drawings of the plains as seen from the Port Hills, shown in Dunedin in September 1948). Most of the landscape paintings of 1948–9 refer to landscapes in the Nelson area, notably Takaka: night and day, The sink-hole landscape and Triple Takaka; like The green plain, these are all ‘memory’ paintings.

Colin McCahon Takaka: night and day 1948. Oil on canvas on board. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, gift of the Rutland Group, 1958

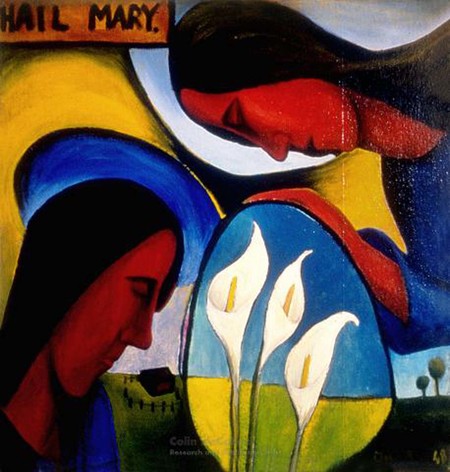

Colin McCahon Hail Mary 1948. Oil on canvas. Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, gift of the artist, 1978

When Takaka: night and day was shown in the 1948 Group Show McCahon remarked on how much more important colour was to his painting at this stage than to the other artists in the show.9 He wrote to Ron O’Reilly:

My big Takaka painting can be seen at last, the full length of the gallery & it’s not so bad. My paintings are the only ones with real colour in the whole show. The Woollastons are all yellow and black seen together and the Hodgkins grey pink and grey green. There are colour schemes (one all over governing colour) but colour as in Brueghel, Piero della Francesco etc no. Colour should say this is yellow and be yellow & this is blue and be blue. Your eye looks from there to there to there to there and sees different colours. Everything isn’t muted and made into a ‘colour scheme’ by being predominantly one thing.10

Most of the religious paintings done at Hewitts Road address subjects from the well-established repertoire of Christian art which he had already explored in 1946–7. Thus I Paul (1948) refers back to I Paul to you at Ngtimote (1946), Hail Mary (1948) is a new version of the annunciation (compare The Angel of the Annunciation, 1947), The Virgin compared (1948) shares a subject with Mother and Child (1947), while there were four new Crucifixions (two since lost or destroyed) to go with the four done in 1947.

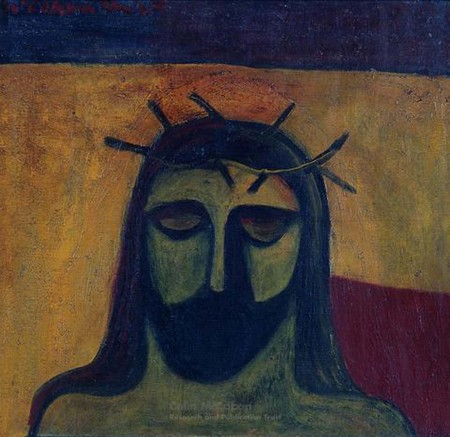

Colin McCahon Ecce Homo 1949. Oil on canvas. Private collection

In general the new religious paintings are painted with more sophistication and less assertive primitivism than before, and with less emphasis on speech bubbles and landscape backgrounds. Brasch wrote of Hail Mary in his catalogue inroduction to McCahon’s September 1948 show in Dunedin: ‘his Hail Mary is a vision of exquisite and tender beauty and seems to express that miraculous annunciation with great vividness and truth.’11

Around Christmas 1948, McCahon admitted a loss of confidence in his painting to Brasch: ‘My illusions of grandeur have suddenly – last night – become small. Am going to paint small pictures of small things. Saying this I don’t wipe off all else I have done. I move on in small ways and this last year perhaps have overstepped myself into a barren field. No, a field I myself have made barren’.12 Presumably the ‘illusions of grandeur’ were provoked by such ambitious paintings as Takaka: night and day and The Virgin compared. In the early paintings of 1949 there is a notable reduction of scale as represented by the January Crucifixion (now in Auckland Art Gallery) and the Head of Christ with thorns (now known as Ecce Homo, dated June).

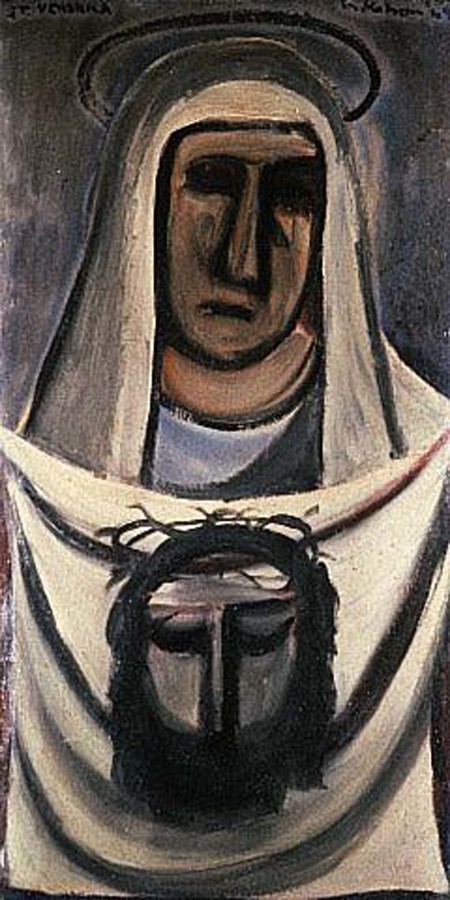

Comparatively little painting seems to have been done in the early months of 1949. Only a couple of Crucifixions and the Ecce Homo can be certainly dated to the first six months of the year. However things began to pick up from about April. McCahon told O’Reilly: ‘[I’ve] been in the midst of new painting movement as from Easter. At last a move, was beginning to despair of it ever coming. What little faith one has at these times & no memory for past times the same. Subjects are the same but edge is sharper, more abstract yet very real – all so far a bit messy but definitely “thicker”. ’13 That year, Easter Sunday fell on 19 April, so McCahon’s revival came from later April 1949. What paintings were involved? Certainly Ecce Homo was one, and possibly also Saint Veronica (1949).

Soon afterwards, McCahon finally found a suitable house to rent in Barbour Street, Waltham, and his family was reunited. The first phase of his Christchurch life had ended.

Colin McCahon Saint Veronica 1949. Oil on cardboard. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, purchased 1981

*

On 3 July, 1949 Brasch wrote in his journal: ‘Colin McCahon … has at last found a house, in Linwood, & brought Anne & the children from Dunedin & moved in – they have been living separated for a year and more.’14 McCahon wrote a vivid account of the new place in his notes to his 1972 Survey:

About now we got a house to live in in Christchurch. It was in Barbour Street, by the Linwood railway station. A Place almost without night and day as the super floodlights of the railway goods-yard s kept us always in perpetual light. The trunks of the trees were black with soot. We eventually had a small but lovely garden. To the right a pickle factory; behind, a grinding icing-sugar plant. Twenty-two rail- tracks to the left. A lovely view of the Port Hills and industry from the front room...15

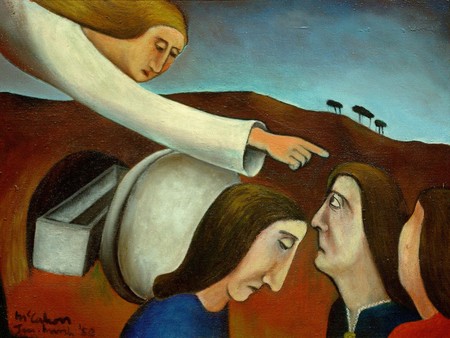

Soon after moving to Barbour Street McCahon made plans for new exhibitions in the North Island – in Wellington a joint show with Woollaston at Helen Hitchings’ recently opened dealer gallery, 30 July – 5 August, 1949; in Auckland, in a hall lent by Modern Productions, 13-30 August. There were twenty-four McCahon paintings in the Hitchings show, most (nineteen of twenty-four) made since his move to Christchurch. Several were exhibited for the first time: The Virgin compared, Plain with winter landscape (now called Canterbury Plain with snow-covered hills), The green plain, Ecce Homo, Crucifixion (1949), St Veronica, I Paul, Crucifixion with rainstorm (now Crucifixion, 1949), plus three large charcoal drawings: Annunciation, Mother and Child, Three Maries at the Tomb. Only two of these new works were landscapes, The green plain and Canterbury Plain with snow-covered hills .

The Auckland exhibition, again shared with Woollaston, consisted of twenty-one works by McCahon, of which seventeen had been shown in Wellington, including all the paintings mentioned above.

Colin McCahon The Maries at the Tomb 1949–50. Oil on canvas on board. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, gift of the Friends of the Auckland Art Gallery, 1960

*

From 1950 there was a noteworthy change in McCahon’s exhibition practice. Between 1947 and 1949, as well as exhibiting at annual Group Shows, McCahon held one or two solo (or two-person) shows each year – in 1947 at Modern Books in Dunedin; in 1948 at Wellington and Dunedin Public Libraries, and in 1949 in Wellington and Auckland – five shows in three years. After 1949 he did not hold another solo show until 1957.16 His annual Group Show appearances necessarily take on additional importance in tracing his development since for almost a decade they are the only means of observing his progress as an artist.

In an undated letter to O’Reilly probably written in December 1949, McCahon confessed that he was temporarily at a stalemate: ‘Myself, am doing nothing at all & don’t feel at the moment that I ever will again. But that will pass. I do feel that all the past has passed & no longer belongs to me, which means that an end has been arrived at but I’m just too tired to build up courage for the next step.’17

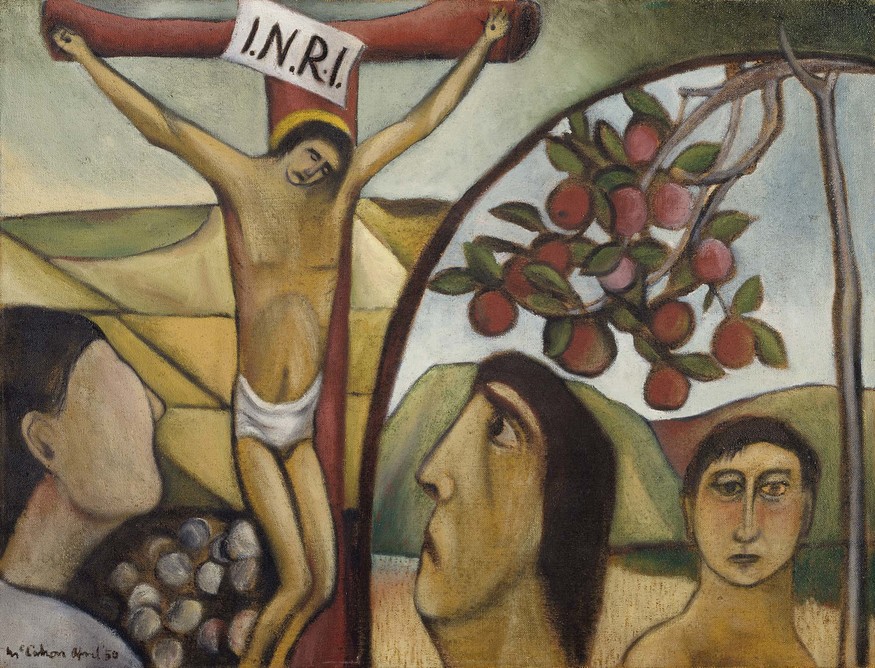

Nevertheless, a new phase in his work was soon instigated by The Maries at the tomb (January–March 1950), a strongly dramatic piece about which McCahon wrote to O’Reilly: ‘My three women at the tomb with flying angel is really something to look at.’ He believed that it manifested ‘something of redemption & not only the fall. If so it is an advance.’18 Inexplicably (unless the catalogue is incorrect) it was not shown in the 1950 Group Show at which McCahon exhibited several substantial new works, including Annunciation (July–November 1949), Easter morning (February–April 1950), Crucifixion: the apple branch (April 1950), Otago landscape (1950), Virgin and Child (May 1950), and A Southern landscape (May 1950).

Colin McCahon Annunciation 1949. Oil on cardboard. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, on loan from a private collection

Annunciation and Virgin and Child both continue the tendency apparent in many of McCahon’s religious works of 1949 of enlarging the figures to fill most of the picture and treating the background abstractly, all landscape elements removed.

Nevertheless, landscape makes a return and figures are smaller and connected to landscape in both Easter Morning and Crucifixion: the apple branch.19 In the latter double work the left-hand landscape including the crucifixion bears a close resemblance to that in Otago landscape painted in the same month, both in colour and in the pattern of horizontal and diagonal lines. The landscape on the right side of the picture enclosed by the curving line is quite different and seems to refer back to the Nelson Hills pictures of 1947–8. The laden apple branch also connects the landscape with Nelson.

Colin McCahon Crucifixion: The apple branch 1950. Oil on unstretched canvas. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, purchased with funds from the Sir Otto and Lady Margaret Frankel Bequest 2004

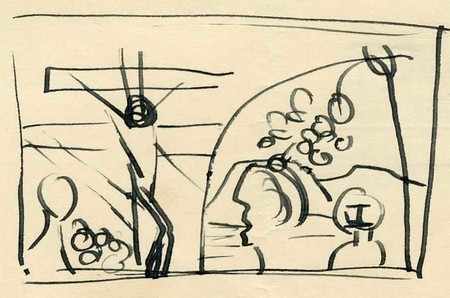

Sketch in letter to Ron O’Reilly, c. July 1950

Letters to O’Reilly reveal that at an earlier stage the placement of the male and female observers was reversed. McCahon wrote: ‘The crucifixion on the left with skulls piled in the front & a very simple & beautiful landscape behind with Mary in the bottom left corner. The right division has a heavy laden branch of apples supported by a forked pole, a landscape of hills & a large head of a man & a boy.’20 In the letter, this is illustrated with a rapid ink sketch.

*

It was later in 1950 that McCahon first began to express the need for a new direction in his art. He wrote to Caselberg, travelling in Europe:

I seem to have arrived at a place to stop painting. Something has been worked out at last – I can now make a start on a new direction. Still very vague, only a feeling & not yet clothed with a subject but I feel the need of a deep space & order, this applied by me & not the earlier order which was so much intuition. I feel I must learn more and make a better foundation for intuition…. after recent work I feel the need for something more conscious.21

The new start seems to have taken the form of a movement away from biblical subjects towards pure landscape. A week later he told Brasch: ‘Have started a landscape (Heathcote) & am finding it most difficult having developed a feeling for landscape & people – landscape without, seems without a heart. But good discipline for the head.’22 The ‘Heathcote’ landscape referred to as not been identified, but Six Days in Nelson and Canterbury (October 1950) may well be an early product of this new thinking. He had used multiple landscapes (in Triple Takaka and The Promised Land, both 1948) before but never on this scale.

Colin McCahon Six days in Nelson and Canterbury 1950. Oil on canvas on board. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of Colin McCahon through the Friends of the Auckland Art Gallery, 1978

Colin McCahon Christ supported by angels 1951. Oil on canvas. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, purchased 1982

In this work the religious content is present only by implication, through the allusion to the Genesis myth of the six days of creation, and the presence of a sliver of (sacrificial?) blood linking all six panels.

From this point on biblical paintings became increasingly rare; only three belong to his remaining years in Christchurch: Christ supported by angels (1951), Crucifixion (1950–2) and There is only one direction (1952). Of the three it is the first about which most is known from his correspondence. He struggled with it throughout the early months of 1951. In April the work was still ongoing:

The new work ex Pieta is still on the way – so slow & hard – I can’t remember any other painting being so hard. A Resurrection it has become, this I’ve wanted to paint for so long and have been putting off, its caught up with me at last. It’s odd how I fight against it & paint in irrelevancies, cherish them & eventually paint them out. I know exactly what I want to do but lack courage. It will be finished by the time you are here.23

Although he included Christ supported by angels in the 1951 Group Show, McCahon apparently told Brasch that he considered the work a failure. Brasch wrote in his journal: ‘An evening with the McCahons – Colin painting Canterbury Plain landscapes, flat & bare with dark lines, scarcely more than abstract maps; only one of three I saw seemed at all successful. His first Resurrection (which grew out of an after-Bellini pieta!) a failure: he said so himself.’24 In May McCahon told O’Reilly: ‘Painting now a series of landscapes from aerial photos of North Canterbury townships.25 These inspired by a film on the Vatican. Such perfection & stillness. I felt the necessity for a change from my past to something more simple & subtle, less obviously emotional, or possibly just a different emotion. That is more correct.’26 One of these paintings was probably North Canterbury landscape (1951), in which the stark geometry of the plains is contrasted in colour and form with the curvilinear anarchy of cloud forms.

Colin McCahon North Canterbury landscape 1951. Oil on canvas. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, presented by the Friends of the Auckland City Art Gallery, 1960

In July 1951 McCahon wrote to Brasch: ‘Last night painted a successful picture, at least began it. A follow on to that large grey green landscape you saw when last here, but more human, much less cold. I feel much better for it.’27 It is impossible to identify with certainty which painting he is referring to here, but the most likely possibility is North Otago landscape (1951), a tawny ochreish landscape, now held in a private collection in Australia, strongly reminiscent of Otago landscape (1950). Significantly, though, he told O’Reilly that same month: ‘But Chch is no longer the cultural centre of N.Z.’28

*

McCahon spent several weeks in Australia in August and September 1951; it was his first time out of New Zealand. Brasch, who had a private income, paid for the trip anonymously (though McCahon knew), believing that he was under-educated as a painter and needed more exposure to high-quality paintings from Europe such as were held in Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria but nowhere in New Zealand. In the event, just as important to McCahon as the works by Rembrandt, El Greco, Goya, Turner, Cézanne and Pissaro he admired in the gallery were fortuitous lessons in cubism he received from an elderly painter, Mary Cockburn Mercer (1882–1963), who had studied in Paris before World War I. While still in Australia he wrote to Brasch: ‘have learned more in 3 days from her than ever before. I only hope she is not exhausted by it. I am both exhausted & elated.’29

After returning to Christchurch McCahon worked on landscapes, a few biblical paintings and his first abstractions (a new development), but he was finding life in Christchurch increasingly frustrating, Brasch reported: ‘Colin is now working as a gardener; everything seems shut against him, the art school for teaching, WEA lecturing; but he goes on painting – at present, large landscapes of the plains but subtler & more varied than his first rather bare & empty ones.’30

In his new landscapes McCahon was attempting to assimilate and apply the lessons of cubism acquired in Melbourne. In several instances, he worked again on paintings started prior to the Australian visit, such as North Canterbury landscape (1951–2) which is inscribed with two dates, nearly a year apart – May 1951 and February 1952. With its elevated viewpoint, this painting uses a strong pattern of diagonals and is decidedly linear and monochromatic, almost like a coloured drawing. It was soon followed by Canterbury landscape (1952) now in the collection of Christchurch Art Gallery, which is dated May–August, 1952. With its rich combination of greens and ochres, this work also depends for its structure on a geometrical grid of horizontals and verticals, with diagonal lines forming repeated triangular shapes. The horizon is even higher than in the previous example, so close to the top of the picture that it appears almost like an aerial photograph.

Colin McCahon Canterbury Landscape 1952. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased with the support of Christchurch City Council’s Challenge Grant to the Christchurch Art Gallery Trust, 2014

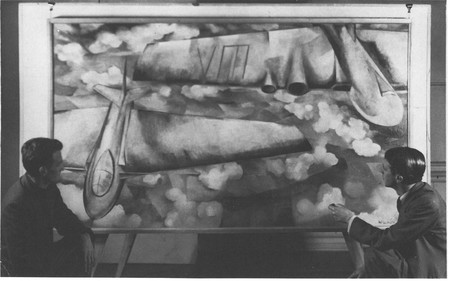

These two paintings pointed the way to the most impressive of all McCahon’s Canterbury paintings, On building bridges: triptych (1952), painted between July and September. This painting was transformed from an earlier work called Paddocks for Sheep. As McCahon said: ‘We lost the sheep and gained a bridge … I had made a very formal statement … the ‘Bridges’, after Australia and Mary, taught me the need for precision and the freedom that only exists in relation to a strictly formal structure.’31 Ron O’Reilly, the most perceptive of the painting’s early critics, said: ‘What has interested the artist is the contrast between the cold, rectangular shapes of the steel, and the warm, triangularly faceted hill country. But in resolving those two patterns he has added a third – the semi-circular one of moving clouds, which is caught up in both the landscape and the steelwork, modifying the angularity and subtly softening the effect.’32

Colin McCahon On building bridges (triptych) 1952. Oil on hardboard panels. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 1958

In terms of religious paintings there were two significant works in 1952: his tenth and last Crucifixion – the completion of a work begun in 1950 – and There is only one direction, his fifth version of a Madonna and Child. The latter work, recently acquired by Christchurch Art Gallery, was to be the last of the forty or so biblical paintings since 1946 – the end of an era. Within a Braque-like oval inside the painted rectangle, the mother’s sorrowful attention is focused on her son, while he gazes directly at the viewer, implicating us in his fate – the cross which is marked on his face by the horizontal lines of his eyebrows and the vertical lines of his nose. For Jesus. ‘there is only one direction’.

Colin McCahon There is only one direction 1952. Oil on hardboard. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, N. Barrett Bequest Collection, purchased with the support of Christchurch City Council’s Challenge Grant to the Christchurch Art Gallery Trust, 2011

Colin McCahon Abstract 1952. Oil on board. The Suter, Te Aratoi o Whakatu, Nelson, gift of John Caselberg

McCahon’s first abstractions were a third development to emerge in 1952, two of which were shown at the 1952 Group Show as Abstract (later one of them, now in The Suter, Nelson, became known as Composition). These appear to have begun in June 1951 – before his trip to Australia – and continued through 1952 (two are dated May 1952) and into 1953. Some are in landscape colours and involve abstractions from landforms; others, such as Composition, are more geometric, involving squares, rectangles, curved segments and the use of black and white.

In December 1952 McCahon was sharply critical of the latest Landfall (of which Brasch was editor):

This last landfall – a trip to hell – redeemed by the [Basil] Dowling poem. But the stories one & all, more or less, without a new direction. You probably look for it too as I do, sunlight rather than the light of the moon – or not even sunlight but at least open daylight. This is where I am trying to go. Away from hysteria into order & value & reality. The other is so half way. Bach rather than Beethoven. Cézanne than Van Gogh. But that will do. Found Westbrook excellent. A very live person…33

Colin McCahon (left) and Eric Westbrook in front of International Air Race (1953), destroyed (photograph, AAG)

Two matters of note appear here. First, the continuing preoccupation with a search for a ‘new direction’, away from ‘hysteria’ and into ‘order & value & reality’ as symbolised by the differences between van Gogh and Cézanne. Second, the reference to Eric Westbrook, the dynamic newly-appointed director of Auckland City Art Gallery, who, after seeing On building bridges hung in the Christchurch Public Library by its librarian O’Reilly, offered McCahon a job in Auckland. McCahon followed up in February with further interesting developments: ‘this week have landed a commission (through Westbrook) from T.E.A.L. for a painting to comme[mo]rate the [London to Christchurch] air race … No strings attached to this & I name the price. To be finished in May. This is really excellent – there is nothing like working for someone else’s needs. ([“]We work best serving needs not our own.” Rilke is it [?])’.34 The commission from TEAL was to occupy McCahon through the remainder of his time in Christchurch, not just the mural-sized painting (later destroyed, whether accidentally or deliberately, by employees of the airline who used it for packaging) but also a number of preliminary sketches, five of which (plus the large painting) he showed as his contribution to the 1953 Group Show.

*

After the McCahons left for Auckland, Brasch, forever a loyal supporter, wrote a thoughtful note in his journal:

The McCahons left Chch this evening. Eric Westbrook, director of the Auckland Art Gallery, has arranged a job in the Gallery for Colin; & if that should come to an end he can at least go out gardening as he has been doing here for a year or more. Chch has been a disappointment to him; he’s sold only one picture here since he came, about four years ago (this is according to Ron O’Reilly: the exception is the landscape which the Priors bought last year; but Rodney & I have bought at least one of his paintings within that time); & he’s had no public recognition except what he’s getting now on account of his sets for the Guild Theatre’s Peer Gynt, produced a week ago…35

McCahon’s future belonged to Auckland. Nevertheless, later he looked back with affection on this richly creative period, saying in 1972: ‘The Christchurch years had been alive with friends and conversations … work and fun’.36

All works by Colin McCahon are reproduced with the kind permission of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust. This article is an extended version of the article printed in B.185 in September 2016.