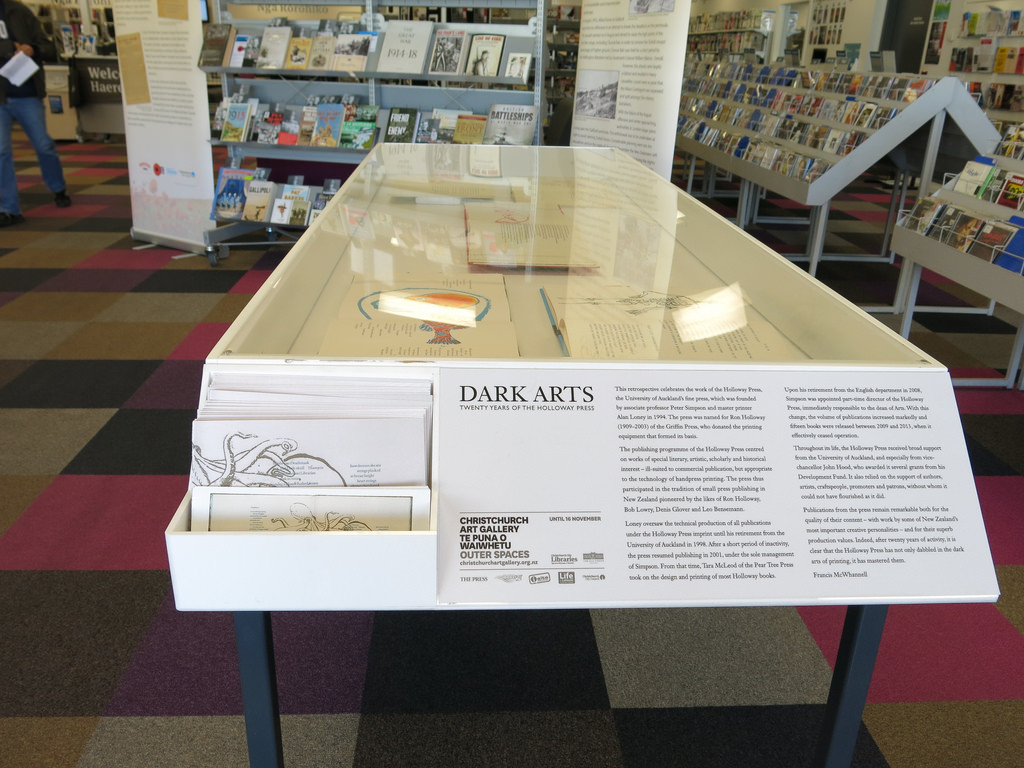

The endless newscape: Barry Cleavin’s inkjet prints

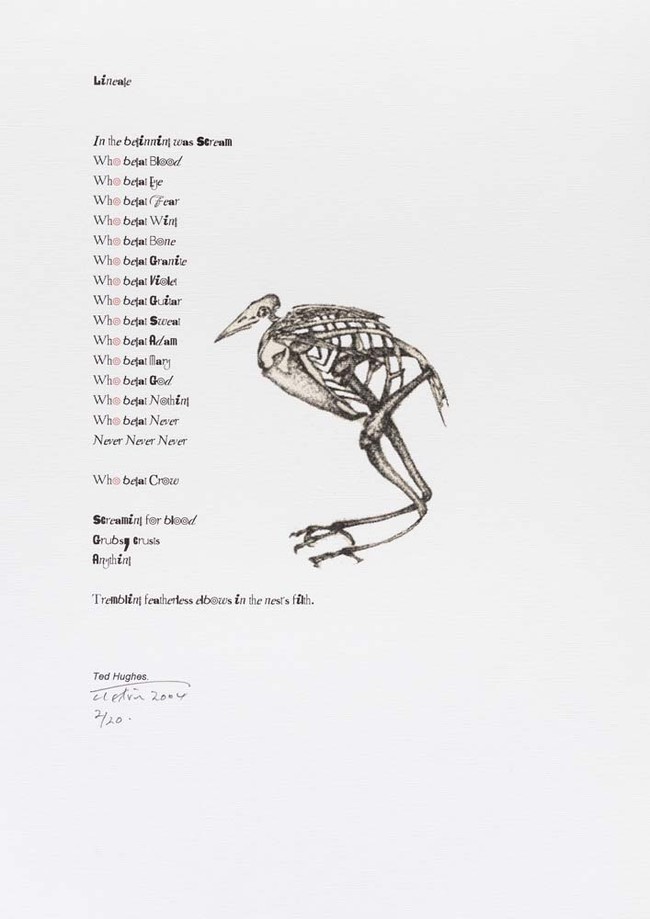

Barry Cleavin Anatomy of a A(NZUS) Predator—from Triad '84 1984. Etching. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1986. Reproduced courtesy of Barry Cleavin

Barry Cleavin is often, rightfully, referred to as a 'master printer' – a maestro of intaglio printing techniques including the complex tonal subtleties of aquatint, soft- and hard-ground etching and the creation of 'linear tension'. Mastering these complex techniques to achieve a command over the etching processes has required patience and fortitude over a career spanning some forty-seven years.

In the catalogue accompanying Cleavin's 1997 survey exhibition, The Elements of Doubt, the artist gave some insight into his working method and the physicality of the etching process:

All the printed works are taken from zinc plates. All the drafting and mark-making is an integral part of my association with the plate surface. This is an intense relationship and remains a challenge even though I have made hundreds of plates between 1966 and now.1

The title master printer also seems justified when considering the influence Cleavin wielded upon a generation of printmakers while lecturing at the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts in the early 1980s. Past pupils of Cleavin's at the school, including Marian Maguire, Jason Greig, Sue Cooke, Kate Unger and Marty Vreede, have all forged successful careers as printmakers.

So having mastered the various processes involved with etching it was a brave and certainly unexpected move when Cleavin suddenly embraced the use of digital technology in his artistic output around 2000. Presented with a computer and printer by his son, Cleavin gave it a 'week or two to prove itself or else it would be out the door'. His close friend and follower of his work, Rodney Wilson, thought the computer had no show. However, his oeuvre expanded dramatically overnight and Cleavin began producing and manipulating digital images which were then printed on an inkjet printer. As Wilson said:

Unexpectedly, the computer could accumulate a library of images. His own drawings, previous intaglio images, illustrations from books, quotations from the history of art, photos, postcards, plastic toys and other banal objects lifted straight from the scanner, and words, type. The library could yield any and all of these in moments, and it could manipulate, distort, change meanings, reverse relationships, turn unrealities, create realities where none existed. FTN_2

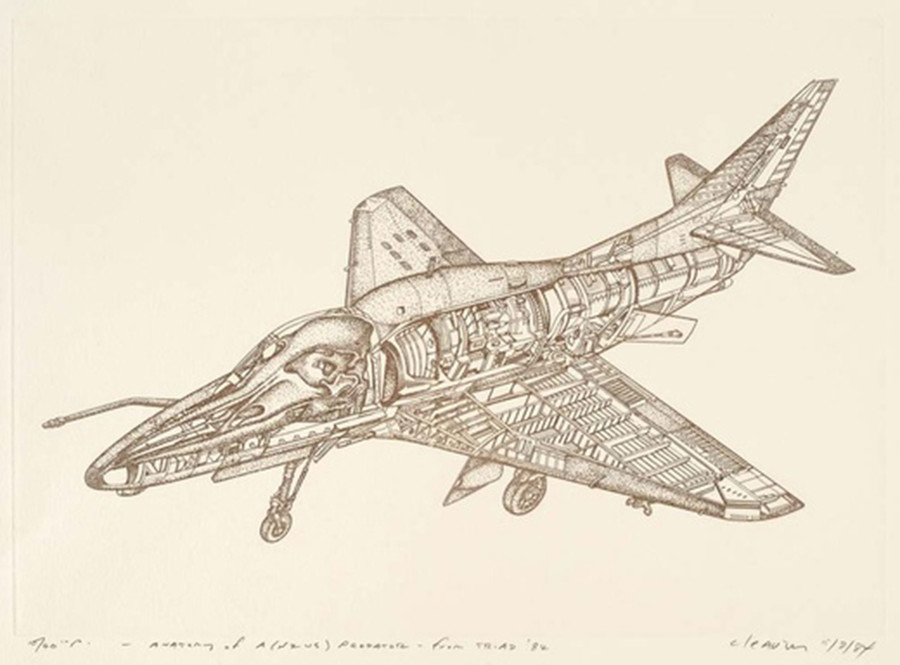

Barry Cleavin Missives—incoming 2004. Inkjet print. From the folio War Torn—A Journal. Reproduced courtesy of the artist

Cleavin's enthusiastic embrace of the inkjet print could almost be seen as an irreverent snub to the age-old printing techniques for which he is revered. But the digital print process has enabled him to greatly expand, develop and pursue his ideas. Far from replacing traditional prints, Cleavin's inkjet prints add to and build on this body of work – they sit comfortably alongside them and are now a dynamic part of the artist's expanded oeuvre.

Cleavin's work is often political with a biting touch of satire. I clearly remember The Elements of Doubt at the Robert McDougall Art Gallery – primarily a survey of his work from the 1990s with a smattering of works from the previous two decades. The etchings on display highlighted the overtly political nature of Cleavin's work, and the challenges he often throws down to viewers in matters environmental. I had recently visited the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC where I saw the fuselage of the Enola Gay on display (an experience which left me feeling very uncomfortable) and I recall relating strongly with Cleavin's sardonic commentary on the nuclear era in etchings like Nuclear Umbrella (1996) and Nuclear Jigsaw (1985).

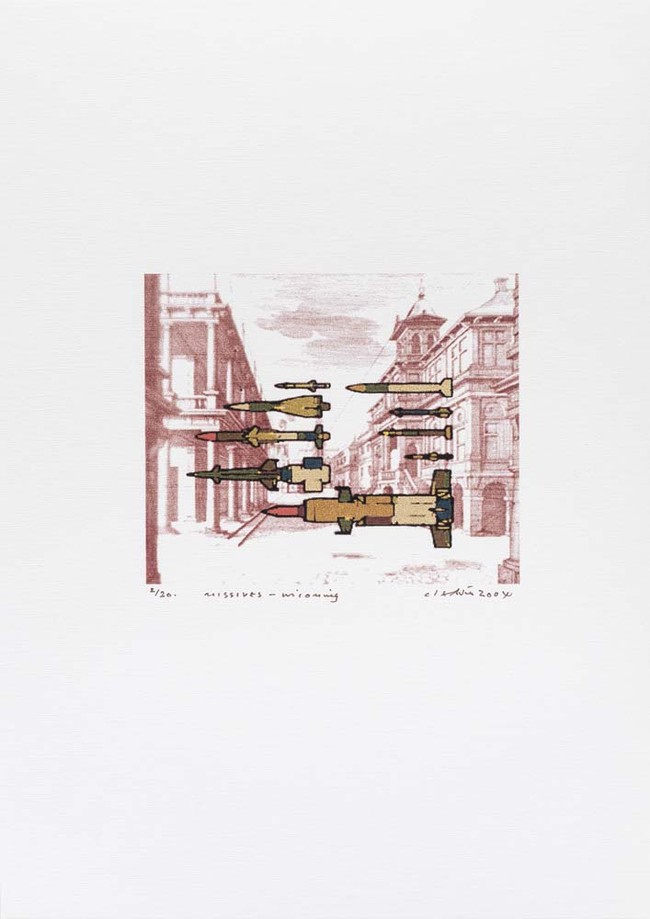

Barry Cleavin Lineage (from the book Crow by Ted Hughes) 2004. Inkjet print. From the folio On War. Reproduced courtesy of the artist

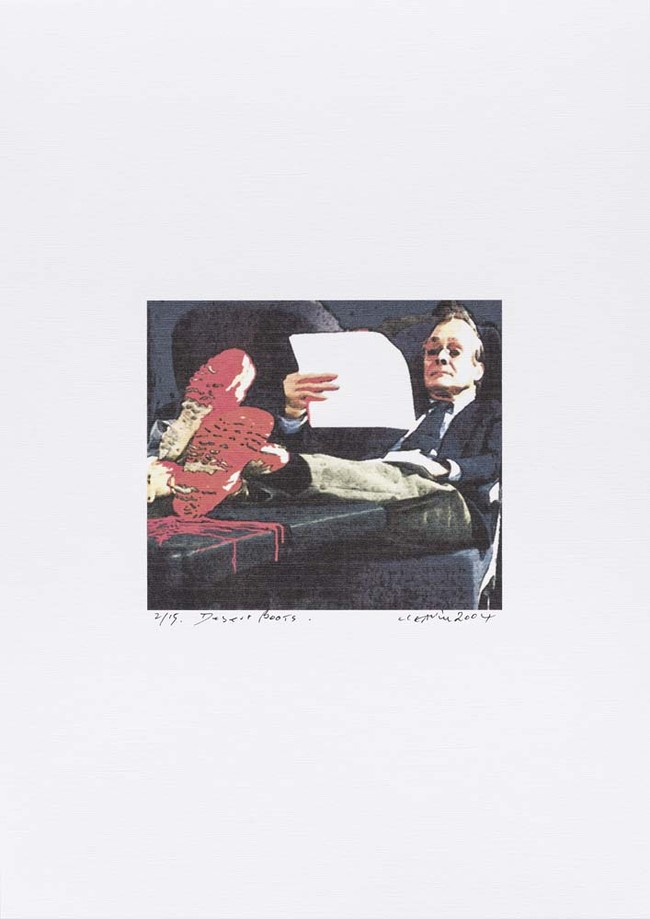

This politicised viewpoint is certainly to be found in many of the inkjet works selected for 24 Hr News Feed, which respond to and comment on current affairs from around the world and closer to home; from New Zealand's own Lombard Four – Kiwi company directors accused of massive investor fraud – who are depicted as defendants in a snake pit, to potent imagery of former US secretary of defence Donald Rumsfeld reclining with blood-stained desert boots. Parallels have been drawn between Cleavin's work and that of Jacques Callot, Francisco Goya and Honoré Daumier; Callot and Goya's respective folios, Miseries of War and The Disasters of War, depict humankind's malevolence in very graphic terms and comment not only on the destructiveness and death inherent in warfare but also the horrific violence that people can become capable of. Similar themes abound in Cleavin's work, and his The Secretary of War or Donald's Nightmares folio points the finger directly at Rumsfeld for the misery caused by the recent Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

In his folio Accessories Not Included, Cleavin asks the viewer directly what part we each play in world politics. Some of the works in this folio seem particularly relevant given the ongoing crisis in Syria, which we in New Zealand all view via a news feed of one sort or another. Cleavin's text on the title page confronts our complicity in current affairs:

Accessories before the fact

Accessories after the fact

Accessories are items that accompany – that are implicated passively or impassively as a supplementary part of an object.

Accessories are what we are when we are involved in a crime, but not present when it takes place.

We sit in a comfortable chair, drink our drinks and eat our food.

Six o'clock – the news – horrors abound

We sit in a comfortable chair, drink our drinks and eat our food.

We, the accessories.

Barry Cleavin Desert boots 2004. Inkjet print. From the folio The Secretary of War or Donald's Nightmares. Reproduced courtesy of the artist

Cleavin's prints have always been accompanied by words, most often the handwritten titles beneath the etched image, which provide the viewer with a direction in which to view the work, if they so choose. In 1982 he commented that, 'I seldom manipulate ideas and images simultaneously. I am not clever with either words or images, they arrive and tend to grow into each other. A collision involving image and word inevitably occurs once I have chosen my subject.' 3

However, in his inkjet prints words now have an even greater presence. The computer has enabled the artist to manipulate text with ease, and words often become an inherent part of his compositions, providing the viewer with another avenue for interpretation. 4 In 24 Hr News Feed the 4 Cautionary Tales folio includes text from Voltaire's novella Candide, which attacks religion and governments and describes warfare as entertainment for kings. Cleavin places an equal emphasis on visual imagery and text, also using writing from Ted Hughes and Carl von Clausewitz, contemplating religious and state-sanctioned terror and violence. Biting passages from Von Clausewitz include 'State policy is the womb in which war is developed'.

Cleavin's inkjet prints highlight the skill with which he responds to world events. This is something that has always consumed the artist, who in 1982 stated that he mostly reduces the world to absurdity: 'in that form it is manageable. I am not bound by notions involving the effects of mass media with its direct communication... The images become cautionary tales...' 5 Cleavin's work provides an alternative and refreshing viewpoint on the craziness and absurdity of the world, as viewed through the mass media's wave of white noise. Constantly washing over us, it is the 24-hour news feed.

Peter Vangioni

Curator

24 Hr News Feed: Barry Cleavin and Locust Jones was displayed at 209 Tuam Street from 6 July until 1 September 2013.

NOTES

-------

1. Barry Cleavin, The Elements of Doubt: Barry Cleavin, Printmaker, Christchurch, 1997, p.26.

2. T.L. Rodney Wilson, 'Some observations on the work of Barry Cleavin', As the Crow Flew, Sequences and Consequences: The Prints of Barry Cleavin 1966–2001, Sale, Vic. 2002, p.35.

3. Barry Cleavin, Ewe & Eye: Barry Cleavin, Auckland, 1982, p.45.

4. Elizabeth Rankin, 'A Word in your Eye: Text and Images in Barry Cleavin's Inkjet Prints', Art New Zealand, no.99, winter 2001, p.67.

5. Barry Cleavin, Ewe & Eye: Barry Cleavin, Auckland, 1982, p.4