B.

Frozen flame, Worcester Street

Behind the scenes

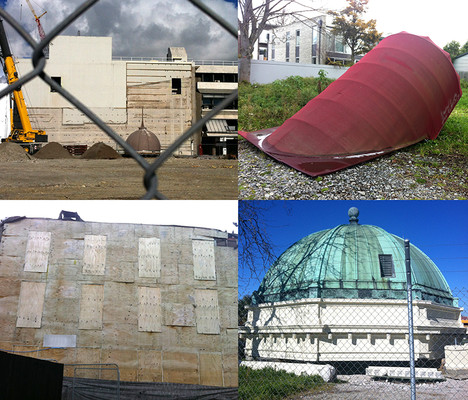

I've been calling it Christchurch's 'everyday surrealism': the commonplace spectacles of life in a post-disaster city. Since the Christchurch earthquakes, the extraordinary has been rendered ordinary by force of daily exposure.

Over the course of a walking a few city blocks last week I encountered, for example, a heritage dome cut off a building and sitting in a vacant lot; a ruined office block completely boarded over with sheets of plywood, flocks of pigeons roosting in the gaps of the grid; and the giant vaulted awning of a hotel abandoned in an wasteland, looming up from the grass and rubble like a portal to another dimension. Things are out of context. Landmarks have disappeared. The built history of the city has become detached from our memory of place.

Yet at the same time, the new city is slowly taking shape. Holes are being dug and foundations are being poured and cranes trace slow arcs against the sky. In this environment of demolition and ruin and rebuild and surreal juxtaposition of the material past with the emerging future, the urban context is constantly changing and everything looks like it could be an art installation.

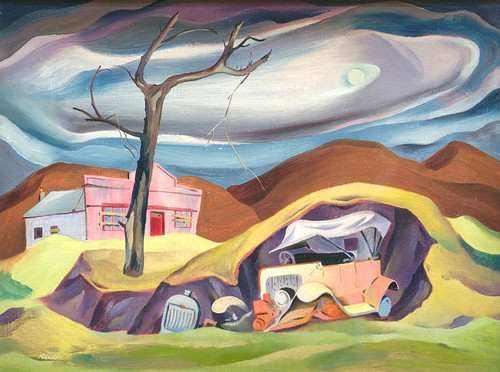

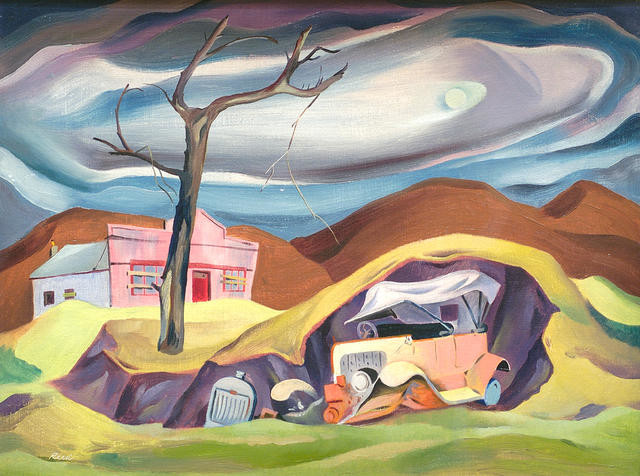

Walking along Worcester Street thinking about this peculiar local category of things-that-look-like-art-but-aren't, I came across something that might fall into a sub-category: things-that-aren't-art-but-remind-you-of-it. In a temporary car park next to the Gallery I saw a dead tree that directly conjures up the early modernist period of New Zealand painting. It looked like it could have been a model for Christopher Perkins's Frozen Flames (1931), now in the collection of the Auckland Art Gallery; or for Eric Lee-Johnson's The Slain Tree (1945), in a private collection.

In his examination of the theme of the dead tree in New Zealand art of the 1930s and 1940s, art historian Michael Dunn observed that many native forests were being burned off in the first years of the 20th century to clear the land for farming; and that 'landscapes of dead or mutilated remains of trees' were common sights in those years, particularly in the North Island.[i] (In Canterbury we have less of a tradition of this theme in local art, as most of the ancient totara forests on the plains had been lost several hundred years earlier.) Eric Lee-Johnson described the dead trees he saw in the King Country as 'mute skeletons' and 'familiar forest ghosts'; Gordon Walters, whose Composition Waikanae (1943), a conté drawing, featured a twisted tree against stark banks of hills, recalled to Dunn that 'huge dead [trees] were a prominent feature of North Island bush landscapes and one did not have to go far to be confronted with them.'[ii]

Dead trees were at once a symbol of modernist 'progress' and a source of melancholy emotion as emblems of loss. Their isolation in a field of destruction spoke to something in local culture between the wars, during the early years of what has been described as the 'nation building' period of New Zealand history.

Dead trees were also a motif of pre-war New Zealand literature. In his poem 'Dead Timber', published in Christchurch in 1925 and a much-quoted example of the genre, Alan Mulgan wrote:

There, on the hillside, is our nation's building.

The tall dead trees so bare against the sky.

In a place with few architectural landmarks, trees stood in for built heritage as a symbol of the local. Mulgan associated dead trees with a particular quality of New Zealand-ness, commenting that while New Zealanders travelled to the world's centres of culture and history ('though we go where memories come thronging'), thoughts of home were represented in the form of slain trees:

Through our delight will creep the voice of longing—

O dear, dead timber on the hills of home!

Critic and historian Francis Pound has, with Dunn, described the dead tree as an 'objet trouvé' [found object] of New Zealand identity from the 1940s and 1950s. It was, comments Pound, a landscape motif which 'struck visitors to New Zealand, and likewise New Zealanders returning to the country, as the clear sign of New Zealand's difference'.[i] The ubiquity of the dead tree in cleared paddocks and on stark hillsides was a unique feature of the New Zealand landscape which gave it a distinctive character. This explains its popularity among the mid-century artists who were determined to make an art distinctively of and from this place, rather than see the New Zealand landscape through imported conventions of representation. However, there were also correspondences between New Zealand artists' use of the gnarled tree motif and contemporary British and American work concerned with representing destruction in the aftermath of war. 'The dead tree theme in New Zealand art,' concluded Dunn, 'was at once symptomatic of a regional awareness and of an international trend.'

In writing about early New Zealand landscape painting, curator Rebecca Rice has considered the 'occupational hazard' of the 21st century art historian: 'one constantly sees the land through the eyes of those who have come before and who have sought to commit their responses to it—its beauty, its challenges—on to canvas, paper, or some other medium.'[ii] She relates this contemporary problem to Francis Pound's earlier discussion of the 'mental frames on the land' that artists carried with them to New Zealand ('golden, cumbrous, elaborate') which determined the ways in which they chose to represent local landscape.[iii] While the first generation of colonial New Zealand artists saw the landscape through an imported frame, and the modernists saw the landscape as a source of distinctive cultural identity, contemporary culture sees the local environment through a series of overlapping filters which comprise its historical representations. Our cities and rural landscapes are occupied by the 'familiar ghosts'—to use Lee-Johnson's phrase—of the artists and writers who have come before us.

With buildings being demolished and erected around it, the dead tree in the empty lot in Worcester Street has been detached from its historical context. It stands, for the moment, like a sculptural monument to another time and place: Christchurch-before-the-earthquakes. It is neither art, nor a source for the contemporary artist: but isolated, vulnerable, defying the odds by standing still in a field of material destruction equated with progress, it instantly brings to mind a New Zealand tradition of visual representation which was in itself a response to a period of great cultural change and uncertainty.

[i] Francis Pound, 'Flaming Stumps: Killeen and the regionalist', Cut-Outs Killeen, unpublished PhD thesis, University of Auckland, 1991, p. 434.

[ii] Rebecca Rice, 'Taking root in New Zealand', in Off the Wall (Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa), issue 1, March 2013.

[iii] Francis Pound, Frames on the Land: Early Landscape Painting in New Zealand, Collins: Auckland, 1983, p.11.