B.

Sutton high-fives McCahon

Behind the scenes

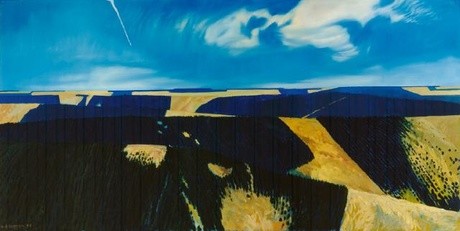

Nothing made it into a W.A. Sutton painting by accident, and the white line that rises diagonally through the sky in Plantation Series II is no exception.

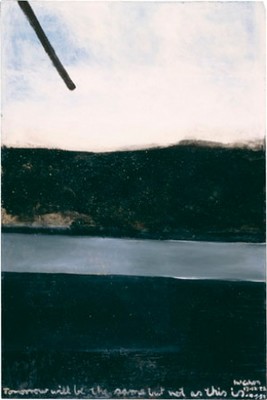

A vapour trail left by an aeroplane? Sure, but if that line feels familiar for other reasons, you're onto something. It's also Sutton paying homage to one of the most famous and mysterious diagonals in the Gallery's collection – the ascending black form in Colin McCahon's Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is.

William Alexander Sutton Plantation Series II 1986. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1986 with assistance from the Olive Stirrat bequest

Colin McCahon Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is 1958–9. Solpah and sand on board. Presented by A Group of Subscribers, December, 1962. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, reproduced courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust