Ripples and Waves

An interview with Salote Tawale

Salote Tawale working on Ripple at Sutton House in February 2023

Melanie Oliver: In the exhibition Ripple, an ocean horizon line locates us geographically and temporally, connecting Aotearoa to your home in Sydney, Australia and also Suva, Fiji. How does the ocean operate in your work?

Salote Tawale: The ocean is a number of places and spaces for me. Physically, I get so much from the energy of the ocean; it helps to centre me and place myself as a small element in a much larger picture. It’s important as a connector, between the horizon, as a way to Fiji.

Almost everyone that I know who has come from elsewhere lives on the edge of the Pacific Ocean. So when I met a First Nations artist from Los Angeles, the first thing that she wanted to do in Sydney was stand in the water and feel that energy.

MO: It’s a shared experience. The hanging paintings were partly inspired by ethnographic photographs showing Indigenous people in the Pacific with their reflections in various bodies of water. How did you come across these photographs and can you share a bit about what they mean to you?

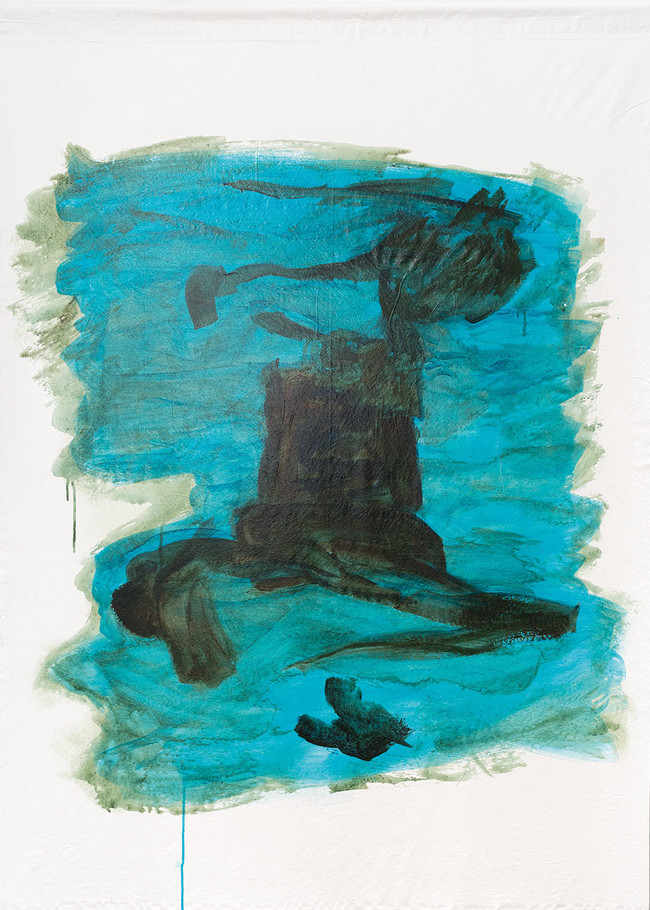

ST: I was doing some research at the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and the first things that I could get in to see were photographs. I’d asked to see ethnographic portraits, but also seacraft – in particular the bilibili, or bamboo raft (which I ended up making for the Asia Pacific Triennial in Brisbane last year). I was looking at these wonderful sepia-toned photographs and holding them in my hand, and the surfaces were just beautiful. Looking at these craft, I was struck by the way that people were reflected in the water, the textures and shadows making these wavy, ripply, upside-down beings. And because some of these people are named incorrectly or not even named at all, I wondered who they were and if I could be related to them; if they could be in my family?

So I was seduced by photographic representations of surface, but I was also thinking about the idea that these people are unknown yet familiar. That led me to want to make these works, painting the surface rather than the person, making an abstract that was already a ripple.

MO: I like the idea that it is indirect portraiture, because the photograph is of the seacraft, rather than the person beside it.

ST: My practice is about connection and disconnection to histories; to now, to things that you can’t know, and to things you feel you might know, if they feel right. I think that in the pseudo-scientific world of collections recognising feelings is as important as recognising connections and disconnections. We, as people who go to look at these things, we notice this, we feel it.

MO: You have an emotional response as well as an intellectual one?

ST: In some ways you’re looking at new things, and in others they’re just settling into place and make sense. I never thought in the past that I’d be so interested in these collections. The Fiji Museum has an awesome collection but I think the Cambridge Museum has one of the largest collections of material outside of Fiji. It’s so weird that you can travel across the ocean, thousands and thousands of kilometres, to visit these objects that used to be on country.

MO: We’ve talked about having wall paintings for this exhibition. Can you tell us a little about the patterns that will adorn the walls?

ST: We’re so used to the white cube space that it’s nice to create a more familiar environment, to change or challenge the architecture of the space. The first pattern will be based on a diamond-shaped weaving pattern, that my Grandma, my Dad’s Mum, would do. She was a weaver who came from a family of weavers and those kinds of arts. She took me to a weaving circle once and all I wanted to do was climb trees, I was just too young.

So that wall will relate to memories and objects, and then the other will be a simulation of the ocean’s horizon line, with this idea of connection to ripples. A ripple can be a memory or it can be some water; we all make ripples in our lives that create connections and disconnections. The main thing is to create the illusion of a space or place and connect to that, the connection to the ocean, to people, to objects.

MO: The other reference point in the work is around masi, Fijian tapa cloth. Has masi played a part in your life and what significance does it have in this work?

ST: In my area of Fiji they don’t make masi, but masi are still used widely in society – we all have masi. Quite often they are used in ceremonies, funerals or weddings, they’re the gifts of exchange. They’re also placed on graves, where they gradually wear down in the natural elements, and then they’re cleared away when the grave cleaning happens. So they have an important place in our family.

I was reading in a book on pre-colonial times that masi were everyday items that could be used as clothing, with patterns for decoration or as an exchange of information, but actually the most highly sought after ones were completely plain because they could easily be given as gifts or utilised for different things.

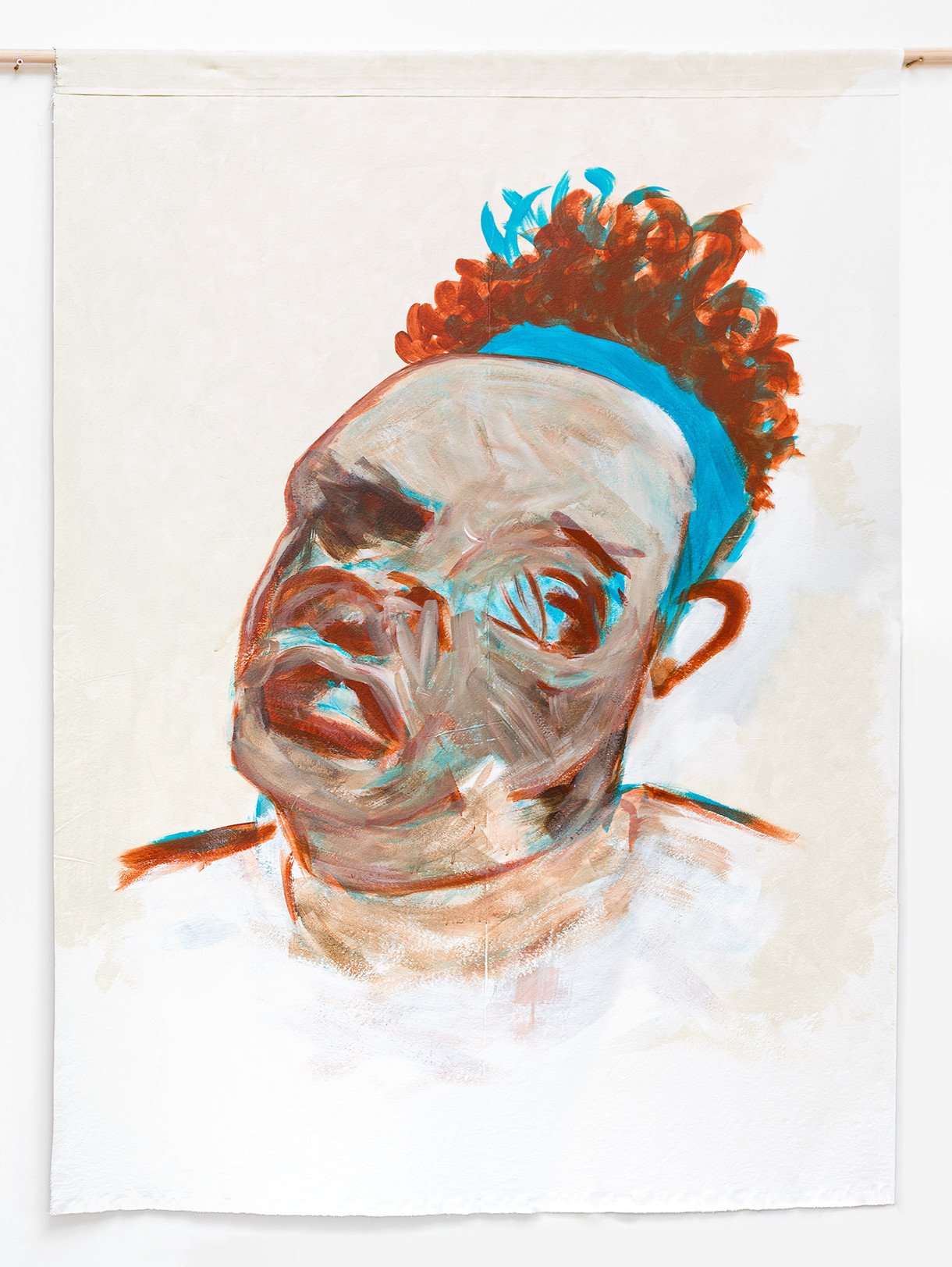

The thing that most interested me though, was that in the old belief systems, in the spirit house there was a masi that went from the upper parts of the house down to the ground and acted as a conduit for the priest to speak to the ancestors. That’s why I design these hanging paintings and they aren’t on stretched canvas. Sometimes I use canvas, sometimes I use calico, but I create a contemporary idea of masi, hanging on a rod, as a way of reflecting on this tradition of transmission to ancestors. Maybe they can see the connection or maybe they don’t even understand it, because in a way it’s in a different language. But I like the idea that masi was an everyday material, this celebration of the everyday and the spiritual.

MO: Video enables you to bring contemporary communication and digital culture into your work, and also seems to be a particularly fun part of your practice. Have you always made video and what role does this play for you? Why do you use it?

ST: I started with video before I was making objects. I had a great photography teacher at high school, and I felt like photography was a cool medium. I was taking pictures of people in the street, I was sitting in the landscape – I liked that contemplative part of it. But then I went to photography school and I began to question why I was taking images on the street, what was the reason to make this into a photograph? Or I’d go into a landscape and spend time making a photo and then think, it’s okay, but it’s not like it is out there. It made me think about why I was making things. What was the reasoning?

Then I did a video class, and I really liked it. At the time we were using standard definition, rather than HD, and it wasn’t as perfect as a photograph. I decided to go and do media arts at university, where I was shown the feminist video artists of the 1960s and 1970s and I was like, is this even art? I use humour in my life a lot to deal with things. And it was kind of funny and awkward and weird. When I started to make work, I turned the camera on myself, following those early questions around why I was stealing other people’s moments. I started to focus on what that means and how you represent yourself and all the elements that are about how we identify.

So I was making videos, and they were humorous, and they were quite often related to video clips or TV shows. Putting yourself in as a Pacific Island body and remaking these kinds of clips is a statement about hidden bodies, and histories that pull away from dominant national narratives. And that was it. That was what I was going to do. Often it’s said you make work about the same thing your whole life, and I think maybe you do. There’s such a vastness about what you can do and how you view things as you explore that. As a video maker I can be really messy or I can make something tightly. Then I started to make video into installation contexts, on plinths, hidden in things. And I started to think, what else? What’s the situation for people?

I began to think about the context and installation of the museum diorama and added more sculptural elements. I’ve become more busy and messy, and I oscillate between filling the space and overdoing it and then pulling back, based on the experience I want the audience to go through conceptually.

I started hiding the screen or adding little things for those that spend more time. Because of the way people view things, I usually restrict the length of my videos to about three minutes – the duration of a pop song. If I make something longer, it has to be for a specific reason.

Salote Tawale Ripple (detail) 2023. Mixed media. Courtesy of the artist

MO: What do you hope people take away from an experience of your work?

ST: There are multiple experiences to have. There are a lot of textures, different forms. For me, it’s about those connections between the present and history, and how something can be meaningful in a photograph, or in an everyday object because it’s such a part of your life and you care about it. I hope people find something familiar. It’s called Ripple, because everything sends out little ripples. Everything we do connects to our future, and comes from our past.

Maybe I can ask you a question. Why did you ask me to have an exhibition?

MO: When I first saw your work, I felt it offered a critique of Western knowledge systems, but it was still welcoming; it was generative and I felt like I could be part of the change process. You’re showing us the problem, but we’re all part of the solution.

ST: There are so many tight expectations within the legacies we all have to operate within. As you try to operate within these systems and structures, it’s hard to work out a place where you can breathe. And that’s what art has made for me – a useful way to explore things rather than get down about it.