Pauline Rhodes: Blue Mind

Installation view of Pauline Rhodes: Blue Mind, December 2020. Photos: John Collie

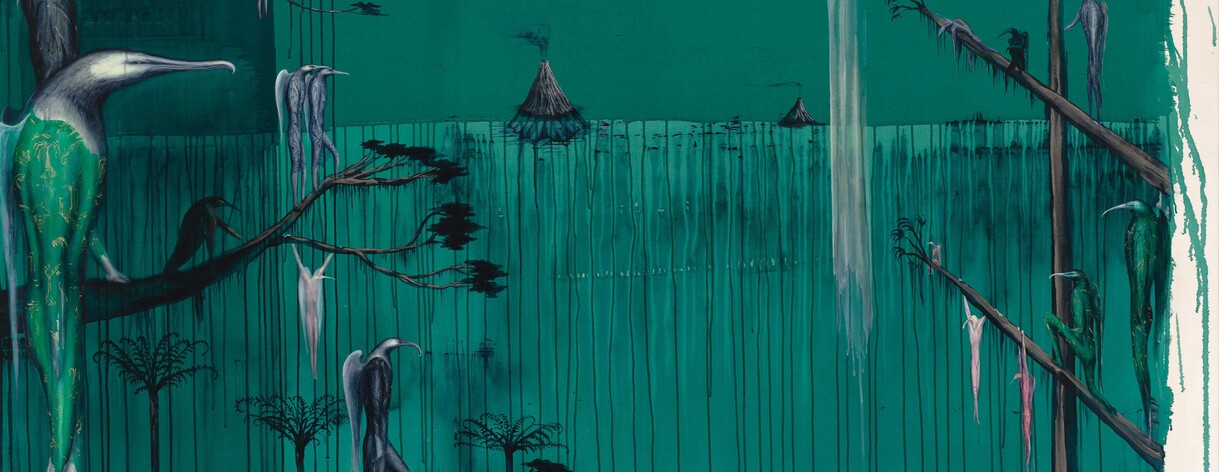

Painted blue and patterned with rust, the thin plywood panels and screens lean nonchalantly around the walls of the gallery and form a skyline of sorts. Across the floor sculptures intersect the space, with groupings of tall rods, waist-high enclosures, clusters of plywood shapes and a small kayak frame on salvaged seaweed and driftwood. Islands for the audience to navigate. The forms are roughly human in scale and relative to the body, generating an intensity and making this an immersive installation to wade through.

If you have seen the work of Canterbury artist Pauline Rhodes before some of these materials will be familiar: the vesica piscis forms that are shaped like the outline of an eye or the overlapping part of two discs; the tripod structures that balance slender blue flames against one another; the thin rods covered in paper printed with text; or the small boat skeleton also wrapped in the pages of a book or newspaper. It is a gathering of old friends brought together in a new, blue monochromatic constellation. There is a sense of calm to Blue Mind, the kind of quietude encountered when out on the water in clear weather, perhaps on a kayak or paddleboard. It’s the feeling of floating in the ocean, a moment of stillness from which you can look back at the shore or out towards the headland and horizon beyond.

Blue Mind is the latest installation from Rhodes’s over 40-year career. Her practice incorporates two ways of working: the making and photographing of sculptural interventions in the landscape, and then gallery exhibitions such as this; what she has termed ‘extensums’ and ‘intensums’ respectively. There is some fluidity between these distinctions, as each informs and is reliant on the other. They can be thought of as producing two different kinds of energy, extending out into the world, or focusing in on an enclosed space. For those who are seeing Rhodes’s work for the first time, this is a sophisticated language of forms, processes and ideas that the artist has developed over the years, arrived at through a consistent engagement with the land, and observation of movement, space and time.

Many of Rhodes’s materials are gleaned from the natural environment, while others are inexpensive industrial products she has gradually acquired to build an array of components that can be recombined and reworked in numerous ways. Once deployed within the landscape or exhibition space, these individual parts are sure to have a long and varied life. Some will be taken into the outdoors, to be placed as temporary sculptural interventions only the artist will see in person and shared more publically later as photographic documentation. Others become part of a gallery installation; propped, placed, balanced or stacked within the space, as they are in this instance; set up to suggest this is just one possible iteration, one perspective and point in time. There is an economy or efficiency to this way of working, a refreshing sustainability of resources, and a development of meaning around certain forms that can be placed in new sites, operating with different constraints and possibilities. Rhodes has characterised this way of working as one that is performed in spite of, rather than because of, the surrounding conditions.

Installation view of Pauline Rhodes: Blue Mind, December 2020. Photos: John Collie

In comparison to some previous installations, the feeling in the gallery is tranquil rather than busy, a space in which to calmly wander and to be revived. The colour blue brings to mind many different connotations and emotions, from depression to clarity, the depths of the ocean to the sky. In addition to the deep blue that fills the room, many of the objects have a layer of rust over the surface, including most of the panels and a long length of wound blue cloth. This use of rusting as drawing or gesture is a consistent part of Rhodes’s process, usually achieved by placing something between two sheets of iron and adding water, enabling the chemical reaction to take place over time. The resulting marks are varied and unpredictable; a deliberate relinquishing of control by the artist, or perhaps an introduction of agency for the materials themselves.

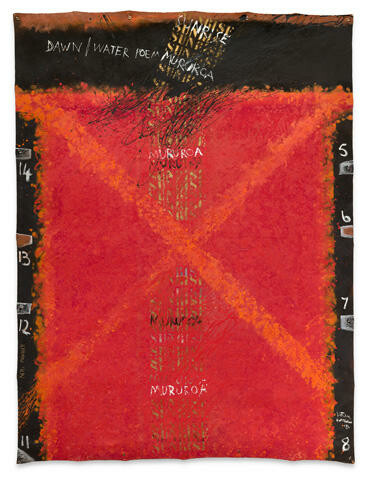

Strips of paper are wrapped around the thin rods and the boat form, black and white texts that are truncated and overlap but still allow some phrases or parts of sentences to be discernible. This creates new readings from existing snippets: “… body at odds… of democracy...”, “… from land that they had taken… a hundred years ago…”, and “… victims… virtue…” The pages taken from everyday literature range from informative to opinionated, and their use speaks to the nature of language as part of the wider textual world, as another kind of structure we navigate daily.

In her incisive survey publication on Rhodes’s work, Ground/Work (2002), curator and art historian Christina Barton locates this unique and distinctive practice within the post-1960s’ expanded sculpture for “its attention to the physical nature and signifying potential of space, its operations in and on time, and its grounding in place.”1 These foundational principles continue to be the ideas that one can use to approach Rhodes’s work, looking to the careful spatial considerations of the works and their relationship within the gallery, the role that duration plays in the materials and how they are used, and lastly the importance of the local landscape and everyday physical experiences of moving through this for the creation and understanding of her work.

Installation view of Pauline Rhodes: Blue Mind, December 2020. Photos: John Collie

Recently, writers have sought to position Rhodes in relation to contemporary theories of new materialism and a range of feminist concerns. Curator Charlotte Huddleston reads her work within the context of Donna Haraway for example, and the way in which we are part of our surroundings, less distanced from nature than once assumed: “not separate from this ecology of time, space and matter.”2 Similarly, writer Rebecca Boswell situates her within the words of Australian philosopher Elizabeth Grosz, to emphasise the complex, dynamic temporal and unfixed qualities of matter and materials as Rhodes applies them.3 What these subtle shifts in publishing around Rhodes’s work indicates is the enduring relevance generated by the openness and immediacy of the work itself – how it continues to speak to our daily lived experiences and ways of reflecting on our current times. Its changing nature represents and responds to our concerns for the environment at this time, and our role and place within this.

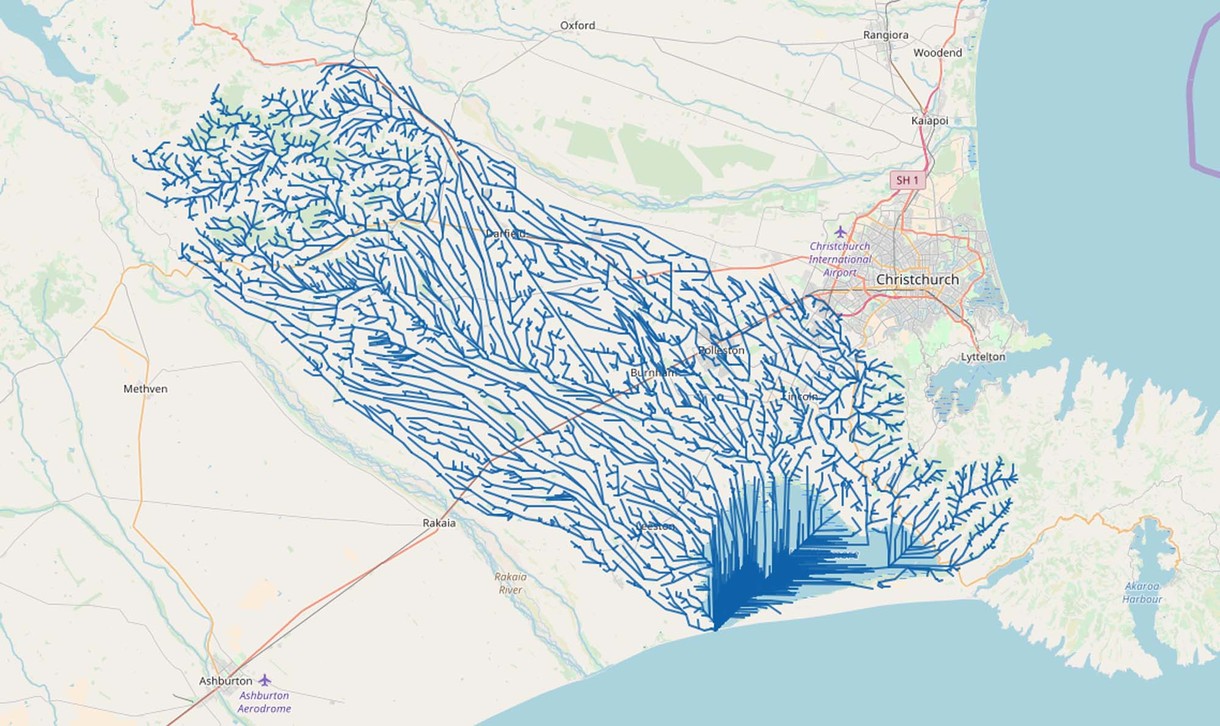

Looking to water instead of the land in the installation Blue Mind, I am reminded of the first time that I encountered Rhodes’s work in person, at the artist-run Blue Oyster space in Dunedin in 2002. Drink II featured large buckets of water, which was pumped around the space through a network of pipes that snaked across the floor of the gallery. The environmental narrative around the sustainability of drinking water was particularly evident in this work, foregrounded through the title and in conversation with the artist. These underlying conservation concerns are no doubt still present nearly twenty years on, yet Blue Mind is a more contemplative iteration, which sees water from a somewhat different direction. Rather than asserting directly political content, this is politics as a way of making and engaging with the world.

Rhodes was for many years a long-distance runner and, as a regular runner myself, I have always connected with this as one way to consider her relationship to the local landscape, particularly the Port Hills and Banks Peninsula, and how the environment filters into her practice. I understand the work being made while in motion, and how it is intended to offer reflection in a perpetually shifting and active state. The artist’s pagework Daily Runs (1986) published in the journal Splash shows the rhythmic leaps of her pen across the page, the only discernible words sketching “the sensuous flow of matter”.4 For the duration of a run, the natural elements of wind, sun or rain locate you in a place through your skin and the texture of the ground beneath your feet informs every step – whether footpath, gravel, grass or sand. Moving through the outdoors like this, my thoughts always keep pace with my stride, allowing for a freedom of thinking that weaves along the narrow sheep tracks, scrambles over boulders or follows the river’s edge. This is my way to reflect and consider possibilities, to turn ideas over and see them from a new angle. While this installation speaks to the experience of being on and around the water instead of the land, it has a similar embodied sense of being in the world. Rhodes allows that sensuousness to emerge through the work with the skyline of the panels around the walls, the soft tactility of the wool tucked into the enclosures, small pieces of shimmering blue glass that are hung to catch the light and move subtly with the gentle gusts of air. Overall the viewer is required to traverse the space, and so must engage – physically, spatially and viscerally.

Rhodes has consistently forged her own path, while always being cognisant of other artists and ideas, and her practice is defined as one way of being, making and living in this world. Blue Mind allows us to look back over her long career and identify some consistent forms or patterns, while also acknowledging that the artist sees more to do, and is at once looking back to the land and out towards the horizon.