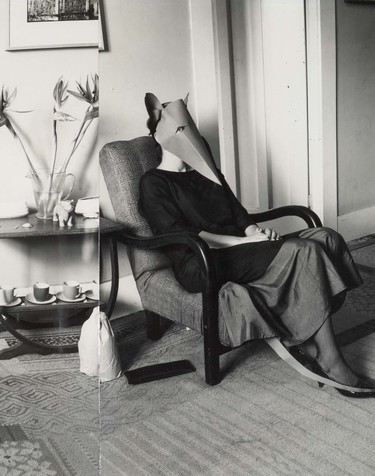

Marie Shannon The Rat in the Lounge 1985. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy of the artist

Marie Shannon talks to Lara Strongman

Lara Strongman: This show brings together thirty years or more of your work, put together with the curators from Dunedin Public Art Gallery. I wondered what you’d discovered through the process?

Marie Shannon: I discovered that I hadn’t moved very far. That’s not to say that I didn’t feel my work had developed, but I’d just run around in such confined territory. Of course that’s not necessarily a bad thing, but I found it confronting to look at that short reach in my output. I had to convince myself that it didn’t all look like shit. (You probably can’t say that here because you want people to come and see the exhibition, but I’m being perfectly honest.) Each time the show was hung, I’d walk away feeling despondent and then I’d sort of think, “No, it’s actually okay”.

I think one of the things that struck me was how close to my subject matter I’d stayed and how I’d circled around the same kind of subject matter. But people do. I don’t think that’s a bad thing, and I don’t think working on a small scale is a bad thing.

LS: Yeah. I’ve often thought of this sort of problem – you have one big idea when you’re about 23 or 24 and then you spend the next thirty years working through it in different manifestations. Or it sometimes seems like that to me. So, when you looked at the exhibition, you felt uneasy at times, but what was the thing that you saw that these works had in common?

MS: Well, very much the domestic location – the location that I could control, that I could work in any time that I wanted. But that wasn’t just convenience. I am one of those people that really likes sitting in a room staring at a corner – looking at the space of a room, at the arrangement of furniture. Locations have their own characters but there is something universal about domestic locations. It’s a background against which you can do things and say things. I really enjoy unspectacular locations. When I first began working in this way, a lot of photographers weren’t seeking out their own environments. They were outward looking and they were trying to put themselves in novel situations to bring back news of the world or bring back news from places that weren’t their own. I knew from early on that didn’t fit with me just because I wasn’t that kind of outgoing person. I wasn’t a person who could bury myself in somebody else’s life or situation.

LS: Let’s talk about failure. You and I have quite often talked over the years about failure and its possibilities. Does that still interest you as an idea?

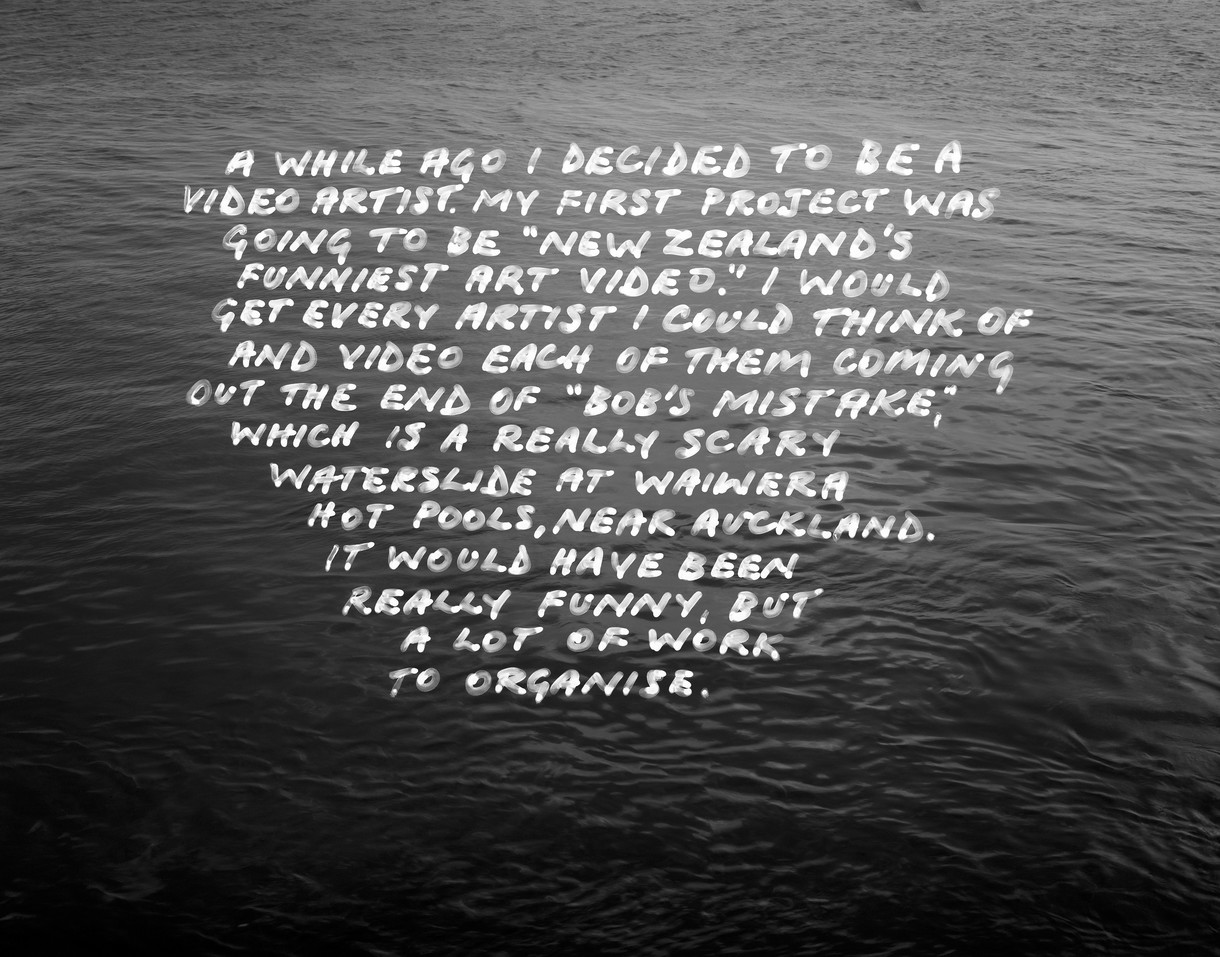

MS: Oh yes. I think everyone has to admit to their failures – and I think everybody’s probably getting a little bit better about that now. There’s more of a culture of not pretending you’re king of the world all the time at the moment. But in a way my work was always kind of a rebuttal to having to put on your best front and always having to be successful. I think there is something to be said for admitting to, and celebrating, failure – doing those things that are a little bit crappy or making artworks that are about the ideas that you had that you knew you actually didn’t have the capability to carry out.

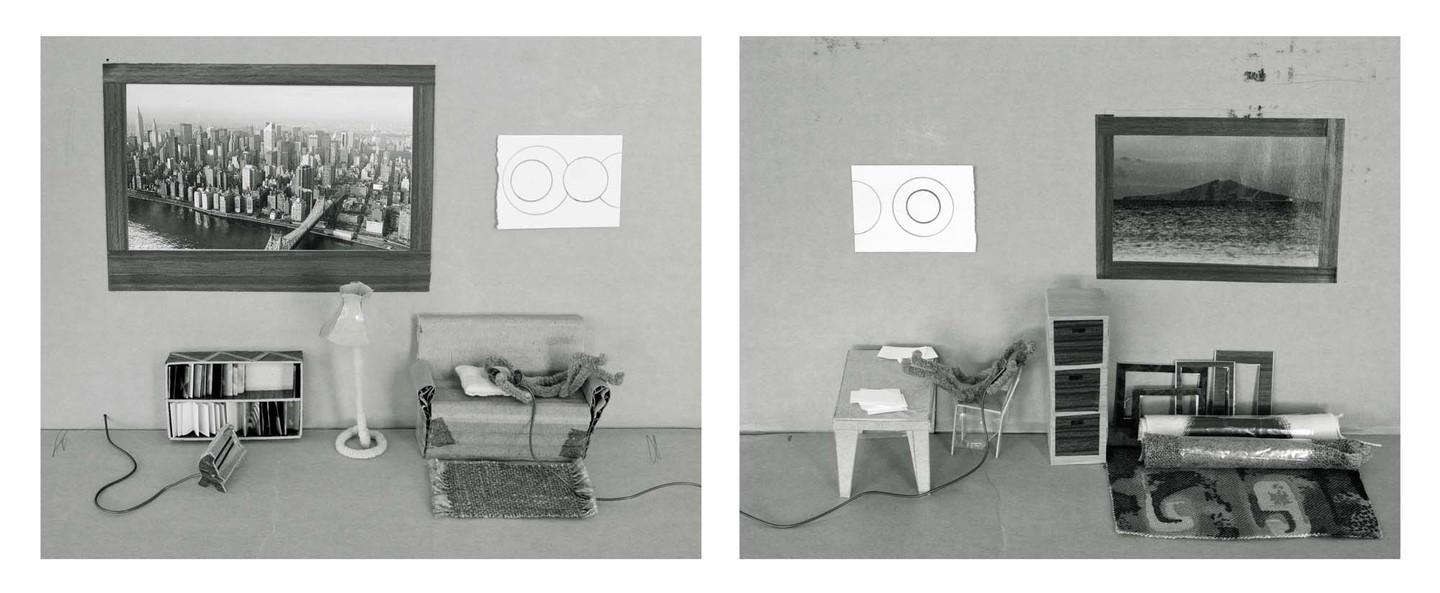

Marie Shannon Phone Friends 1990. Silver gelatin print (diptych). Collection of the artist

LS: In a way your first video works were actually photographs, about your ideas for videos that you never made. The art bloopers, and so on.

MS: Yeah, I was going to be so good at making videos.

LS: Why did you make the switch to primarily working in video?

MS: In 2011 I made What I’m Looking At and that was the first of the text videos. Afterwards, I went back to video when I had material that seemed to manifest itself as text. It obviously wasn’t going to turn into a book that people would want so I was thinking about making a visual object and having moving or animated text in some way. The text was generated out of the situation of Julian dying, when I had to deal with the studio and the contents and catalogue a lot of stuff. And so that was really what I was immersing myself in. I like that way of writing by making lists because it affords the possibility of juxtapositions. Lists allow you to bring things together in a way that’s quite powerful. You can talk about things that wouldn’t normally sit together.

LS: Given that text has appeared in your work from the beginning, how do you see the relationship of your photographic practice to narrative?

MS: My photographs often imply a story or tell a fragment. In the early years, I would set these things up, derived from an everyday situation that had narrative possibilities or photographic possibilities.

LS: Like Rat In The Lounge?

MS: That was a real situation that obviously had good image potential and so I restaged it.

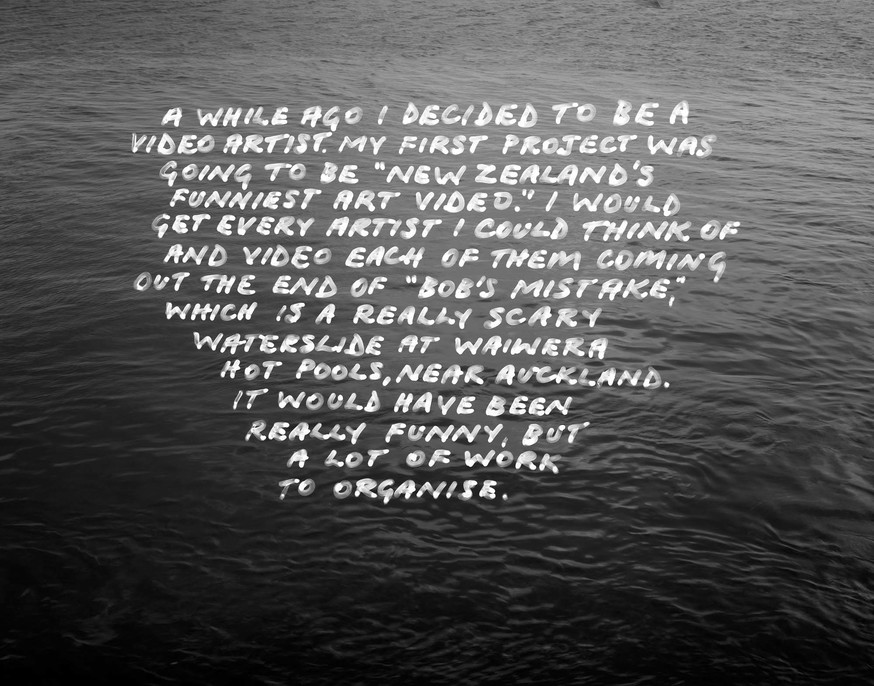

Marie Shannon New Zealand’s Funniest Art Video 1994. Silver gelatin print. Collection of the artist

LS: I want to ask you about the shape of your practice over the years. You’ve tended to produce bodies of work over time. Sometimes quite a long time. And sometimes there have been long gaps between those series. I wondered if you could talk a little bit about that from the vantage point of looking back through your work on the occasion of the show?

MS: Yes, that’s true. There have been threads that have carried on, and there have been themes that I’ve not resolved at the time but later the way to resolve them has become clear. There are bodies of work that aren’t represented in the show. There were several bodies of work that looked at creative processes in themselves. Photographs that were almost like demonstrations of how to make something. They were based on the process photographs that you used to find in mid-twentieth-century cooking books.

LS: Have you always worked consistently, Marie? In your studio practice, do you work every day or every week or whatever?

MS: No. There are really long gaps because I am someone who lets life get in the way and I find it very, very difficult to keep working if too much other stuff is happening. And you know, I can’t turn my back on things. I can’t turn my back on people. When I had Leo, I really thought, “Okay, this is it. I’m not going to try to do anything. I’m not going to try and keep working right now” because I knew I would resent my baby for you know, sitting there wanting me to do whatever babies want you to do. I’m not someone who can snatch half an hour at a time and quickly jump into that space that you need to be in. I tend to need to sneak up on things over quite long stretches of time.

LS: How do you know when ideas have percolated?

MS: It’s just when you actually start doing stuff. You realise the thinking process is over or that the back of the mind process is over and you know, “Oh, it’s time to actually make this thing now”. Suddenly I think it might actually work, it might not be the world’s dumbest idea.

Marie Shannon: Rooms found only in the home was developed and toured by Dunedin Public Art Gallery.