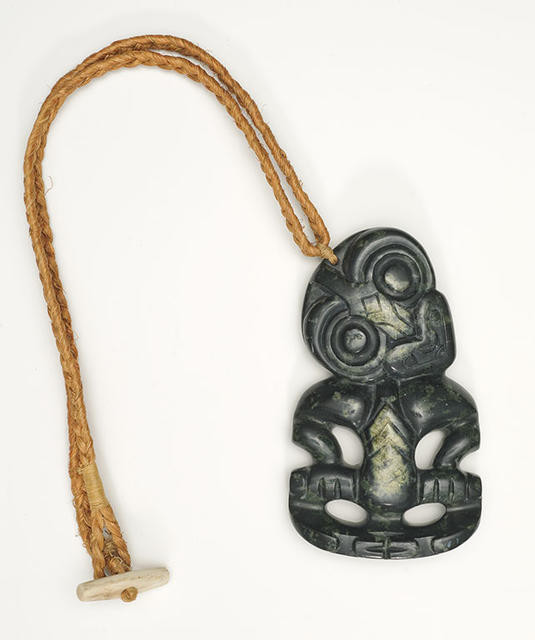

Lisa Walker Pendant 2016. Pounamu, silver. Courtesy of Galerie Biro, Munich

Lisa Walker: 0 + 0 = 0

It might be tempting to say that Lisa Walker makes jewellery out of any old thing – but it isn’t true. The eclectic objects that form her distinctive necklaces, brooches and other body-adornments are meticulously selected and shrewdly modified before they see the light of day. She salvages her materials from an unlikely cornucopia of sources – re-presenting objects such as car parts, animal skins and even kitchen utensils through the frame of body adornment’s long history. Tiny Lego hats, helmets and hairpieces – of the kind that clog vacuum cleaner nozzles in children’s bedrooms around the world – are strung on finely plaited cords like exotic beads or shells; trashy gossip magazines are lashed together to yield a breastplate befitting our celebrity-obsessed culture; dozens of oboe reeds donated by a musician friend bristle round the wearer’s neck like the teeth of some unimaginable deep sea leviathan.

Walker’s work doesn’t sit comfortably within the contours of conventional jewellery – it squirms, fidgets, stretches and unravels. ‘I want to make pieces that don’t fit any of those jewellery recipes, yet still make sense as jewellery,’ she once said.1 In a field known for refined finishes and seamless construction, her audaciously sized, deliberately low-tech pieces inject a blast of pure creative oxygen, wilfully disobeying established jewellery conventions and confounding audience expectations. Despite their bodged-up, glued-together appearance and gleefully tacky origins, Walker’s works are anything but haphazard – rather they are elevated by her acute sense of colour and composition and healthy sense of irony. The new and recent pieces included in her Christchurch Art Gallery show, 0 + 0 = 0, explore a range of critical concerns; confronting jewellery-specific preconceptions about wearability and craftsmanship, they also investigate the politics of value, identity and appropriation.

After receiving a traditional jewellery training at Otago Polytechnic, Walker moved to Germany in the mid-1990s to study with influential jeweller Otto Künzli at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. The anarchic approach she honed there has made her jewellery keenly sought-after, both within New Zealand and internationally, and in 2010 she received the Françoise van den Bosch Award – a prestigious international prize given once every two years to a jewellery artist whose work demonstrates outstanding quality and appeals to younger generations. Last year, New Zealand’s Arts Foundation honoured Walker with a Laureate Award, citing her originality and the influence of her practice.

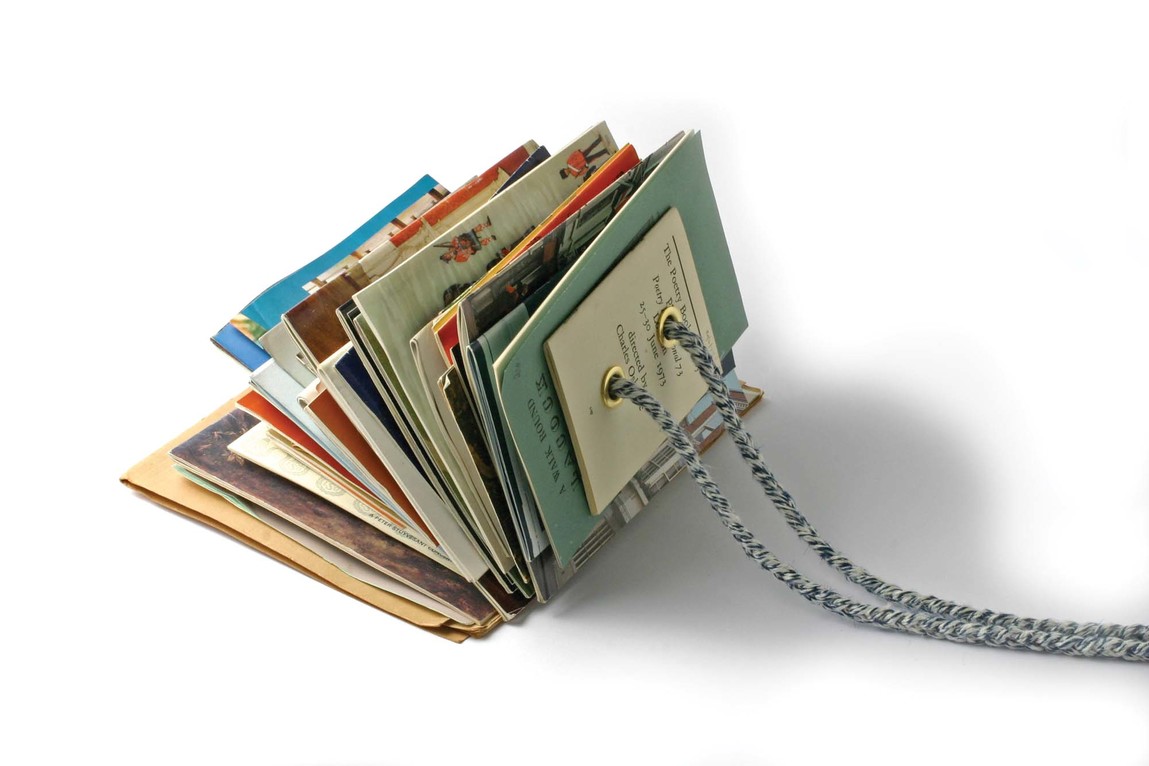

Lisa Walker Trip to Europe 1973 2011. Documents, brass, string. Courtesy of the artist

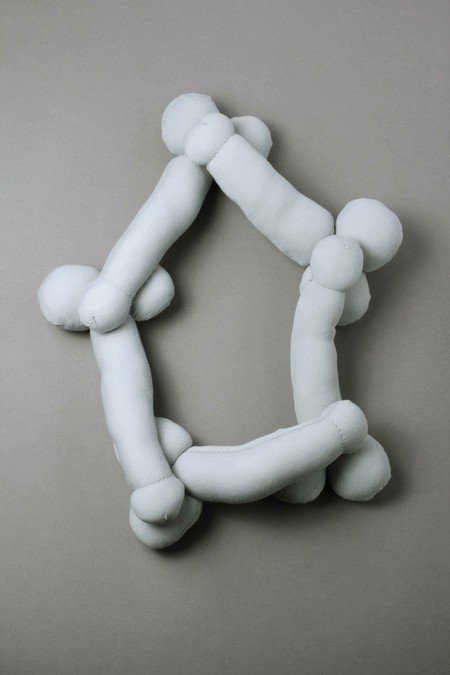

Lisa Walker Dick Necklace 2016

While some of Walker’s materials are amassed close to home – she once made a necklace from six months’ worth of detritus collected from her studio floor – she also ranges more widely, combing the world of the non-precious for idiosyncratic treasures. Together with physical objects, she collects memories and associations, a process made explicit in Trip to Europe 1973 (2011), a necklace, constructed from the postcards, train tickets, concert programmes and other souvenirs a ‘cultured couple’ offered for sale on Trade Me. For Walker, having just returned home after fifteen years spent living in Germany, the mementos spoke of New Zealand’s complex history of arrivals – including those of Māori and European settlers – and of how cultures are transported, translated and transformed. Recent pieces such as Pendant (2016) reflect her interest in (and ambivalence about) exchange and appropriation and especially how these might play out within a New Zealand context. Assembled from pounamu offcuts given to Walker by a sculptor friend, Pendant combines varied surfaces cut from several different stones, offering a beautiful, but deliberately problematic, addition to the tradition of Māori taonga.

Despite the irreverence of its title, and the ubiquitous banality of the phallic graffiti that inspired it, another, equally serious, reclamation prompted the creation of Dick Necklace (2016).

I live with the challenges of a patriarchal world and [its] hideous anti-women history. I’m intrigued by the online activity of the younger feminists. I was always impressed by Louise Bourgeois’s giant bronze cast penis sculpture [Filette (1968)]. Many years ago I saw a postcard of her as a 70-something year old woman, standing next to it with her hand gently, but authoritatively, resting on the giant penis. ‘Dick and balls’ drawings are a cultural phenomenon; we grow up with these scrawlings everywhere. The penis can be symbolically positive and negative; fertility and love, but also rape, misogyny, imbalance of power. As a feminist I now take, claim, and interpret it for myself, twisting its symbology into something else.

‘I learned a long time ago that you don’t have to find the answers. It’s enough for the works to keep asking the questions.'

The thorny issue of copying and influence has long fascinated Walker, gaining new relevance as social media allows for the increasingly unrestricted distribution and repurposing of imagery of all kinds. She joined Instagram, the online image-sharing service, in 2015 and describes it as a ‘huge hunting ground’,2 admitting she is now influenced more by what she finds online than by actual, ‘real world’ objects. A posted shot of Masturbine (1984), a well-known work by the renowned contemporary Swiss duo Peter Fischli and David Weiss, prompted her own Fischli & Weiss Bracelet (2016), which replaces the original’s whorl of expensive leather footwear with budget heels from her local Number One Shoes warehouse. A photograph of a cellphone bound up in the twisted cord of an old-school desk phone, uploaded by the Los Angeles-based artists Mitra Saboury and Derek Paul Boyle under the Instagram nomenclature ‘Meatwreck’, proved irresistible. Walker recreated it, almost exactly, in the form of an oversized pendant and, though she remains delighted with the piece, doesn’t shy away from the questions about ownership and creative license this kind of borrowing provokes. In fact, the discomfort inherent in such appropriation is shared by artist and collectors, since Walker’s works are primarily designed not to be displayed politely indoors, but to travel with their wearers out into the wild, wide open of the public domain. ‘I learned a long time ago that you don’t have to find the answers,’ she says, ‘It’s enough for the works to keep asking the questions.’3

Lisa Walker Fischli & Weiss Bracelet 2016. Shoes. Courtesy of the artist

If the eclectic forms of Walker’s work reflect the democracy and limitless possibility of our new open-source world, her ‘more is more’ aesthetic also suggests the sense of chaos and overload it can provoke. With every online image potentially linked to thousands more, how could you ever see it all? Excessive, oversized, popping at the seams with look-at-me impudence, Walker’s works draw upon and reflect the unrelenting abundance of modern life. And yet, taken one piece at a time, they’re much more than thrown-together clickbait. At its most anarchic, jewellery that is created to be worn still requires its maker to take into account a series of

considerations that don’t constrain other art forms, like painting or sculpture. As she creates her pieces, often concealing traditional jewellery processes beneath contemporary kitsch, Walker thinks about weight, scale, durability, and how her pieces will relate to the yet-unknown body they are destined to adorn. Having thrown out the rulebooks in her early practice, she now values the technical challenges these self-imposed limits present, enjoying how they slow things down and distil her attention, demanding mindful focus in a fast-moving world. In discussion, it soon becomes apparent that this process fuels, rather than suppresses, Walker’s high-voltage imagination. Recalling a project in which she turned an entire building (City Gallery Wellington) into a brooch by clipping a giant mild-steel safety chain to its ceiling and attaching the other end to a wearer via an enormous pin, she mischievously refers to it as only her ‘second largest work’. She’s not kidding; the scale of that audacious project is effortlessly eclipsed by another one. Existing, so far, in solely conceptual form it features a chain, pinned to its wearer, with planet Earth on the other end.