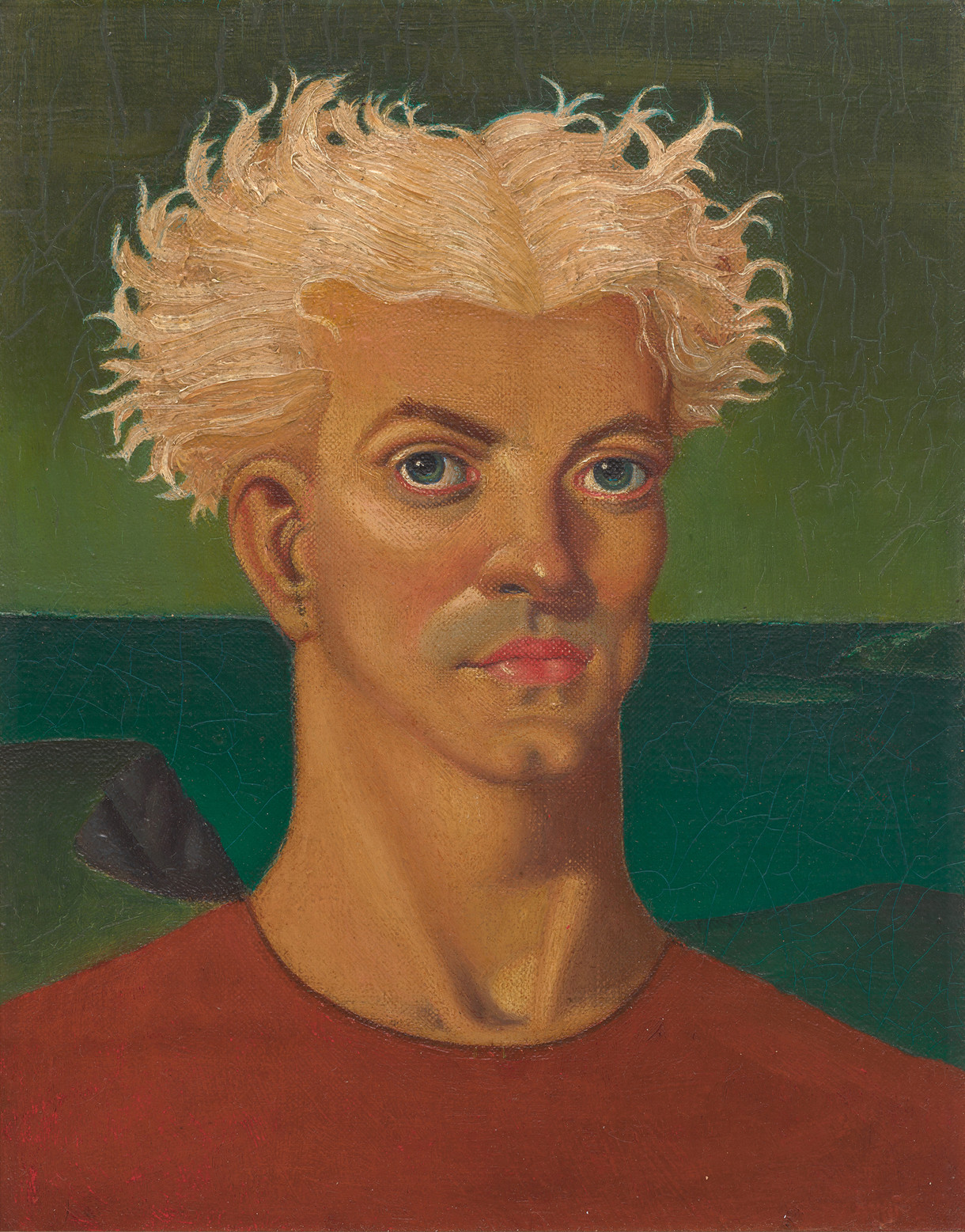

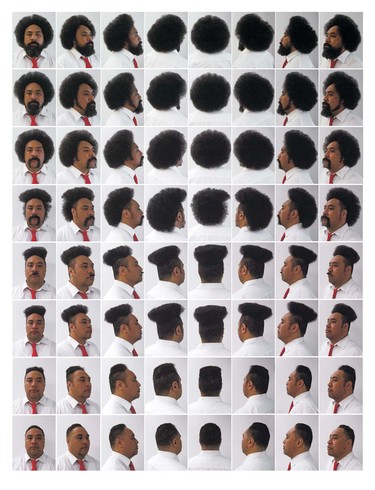

Siliga David Setoga Oki fa’a-kama-Samoa-moni lou ulu (Cut your hair like a true Samoan boy) 2014. Photograph, inkjet print on Hahnemühle Matt Fine Art paper. Photographed by: Setoga Setoga II, Barber/hair stylist: Maligi Evile Jnr. Courtesy of the artist

Hair Story

In drawing attention to the theatre of personal grooming, Bad Hair Day brings together portraiture and caricature with a variety of less readily classifiable works of art. The densely packed selection spans a vast historical range. And in putting bowl cuts and bushy beards alongside wayward wigs and whiskers, it highlights the sometimes comical aspects of hair, especially when styles are extreme. If wry intent is discernible throughout the exhibition, however, we shouldn’t let this fool us: hair is a topic that easily turns serious.

A cautionary note also belongs to the show’s gag title: although the hair on display could be rated if necessary, little of it is truly bad. Of more interest is the way in which, with works grouped roughly according to categories (wigs, facial hair, tricky cuts, long black or long blonde…), the similarities and differences start talking to each other. It is possible to read the works according to timelines, changing fashions and ways of thinking about personal grooming down the centuries. There is nothing terrible about most of it – it’s just how styles change. The Portrait of a Courtier attributed to Robert Walker, for example, shows a long-haired and bewhiskered style that was conventional in the 1650s, but likely wouldn’t be seen today.

Ideas relating to time and change also come into play in Siliga David Setoga’s Oki fa’a-kama-Samoa-moni lou ulu (Cut your hair like a true Samoan boy) (2014), a gridded series of photographs in which the artist makes a provocative formal statement about identity through his own hairstyle. It is both satirical and deeply serious – the title being a challenge to the artist from his father, who had arrived in New Zealand in 1961 and wanted for his son the neatly-trimmed style of that particular period, as seen in the bottom row of photo portraits. The Niu Sila-born Setoga, however, more comfortably pictured at the top of the chart, wryly challenges prescribed expectations relating to cultural identity, from a different generational viewpoint at least. This work, like many of those selected, can also be read in relation to how hair defines personal space.

David Cook’s photograph Punks go on Rampage in City (1983) connects to a similar idea, a reminder of how punks and rebels in early 1980s Christchurch and elsewhere used hair to signify difference and define an alternative cultural space. Their adopted hair statements functioned as both warning signs and buffer zones between the wearer and the prevailing, homogeneous society, creating a useful barrier. In contrast, the eighteenth-century Englishman Leonard Mapes Esq., of Rollesby, Norfolk used his 1735 coiffure as an expression of the society and cultural values he wished to embrace. Mapes’s white-powdered wig and impressive embroidered coat signalled who he was and where he belonged. These were part of an en masse gentlemen’s agreement, where well-off adult males wore wigs as a means of confirming their place in society, their fashionableness, refinement and status.1 The taste for these started in France in 1624, mainly due to kings Louis XIII and XIV both going bald at a young age. The fashion took off in England the 1660s when Charles II began losing his hair, and endured for the next 140 years. Reflecting the spillover effect of that particular period in fashion, Steve Carr’s video work Aona (2010), made while on an artist residency in Japan, shows its enduring influence on French poodle grooming style.

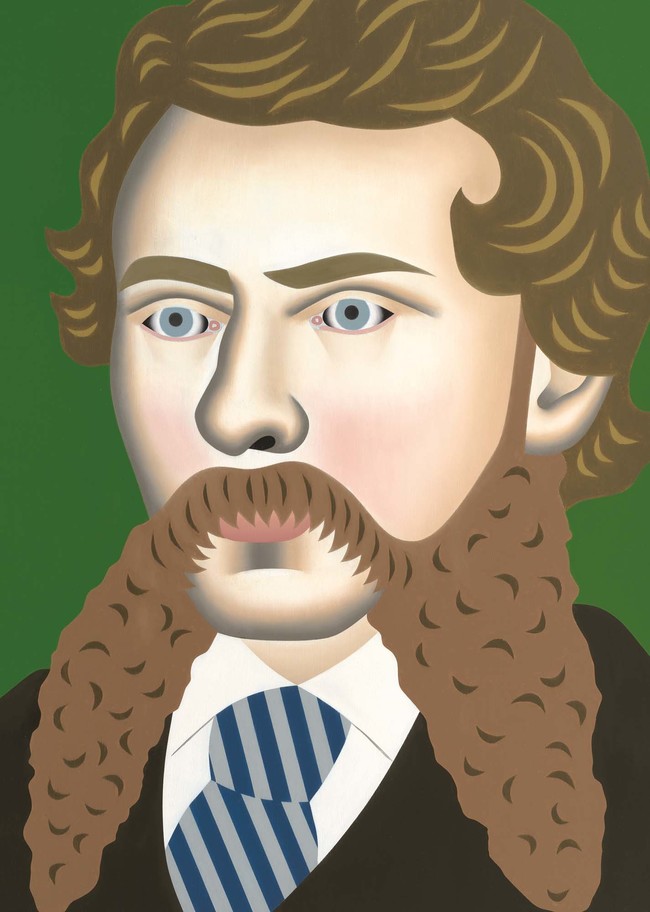

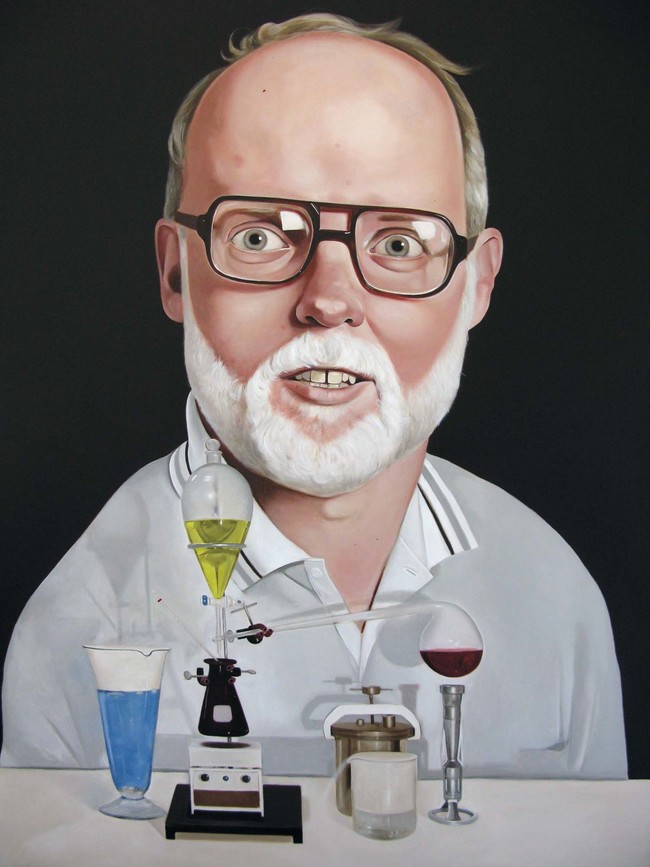

Gavin Hurley Big Henry (Wynn-Williams) 2016. Oil on linen. Courtesy of the artist and Melanie Roger Gallery, Auckland

Ideas attached to approved cultural codes and hair presentation rituals also exist in Our Country’s 24 Examples of Filial Piety (1882), a spectacular three-part woodblock print by Japanese artist Toyohara Chikanobu. The theatrics of style are heightened by the fact that it depicts a kabuki drama scene, further underscoring the link between hair and performance. Similar thoughts may be applied to the dramatic mutton-chop whiskers of early Christchurch lawyer Henry Wynn-Williams, a different type of performer whose facial showmanship is highlighted in two portraits. The first, an 1860s oil-painted photographic portrait, is a likeness he would have procured from an early city photographer’s studio.

The second, painted a century and a half later, is a blown-up version by Auckland-based Gavin Hurley that puts men’s facial grooming from the colonial era under a double spotlight. This particular style would have been especially startling in court, where Wynn-Williams wore a hairpiece similar to the one sharing space with his portraits: an elaborate horsehair wig, London-made, worn by an early Christchurch town clerk.2

The wearing of wigs by legal professionals in court was clearly intended to bulk out their formidable aspect and, for William Hogarth, invited a satirical response. Hogarth’s The Bench (1758–64) depicts an engraved array of outrageously bewigged or bearded characters in various states of caricature. This is accompanied by a summary treatise on caracatura, or distorted drawing for satirical effect. Laying out his thoughts beneath the picture, Hogarth expresses admiration for a ‘famous Caracatura of a certain Italian Singer, that Struck at first sight, which consisted only of a Straight perpendicular Stroke with a Dot over it.’3

As if picking up cues from Hogarth three centuries later, Christchurch-based Leo Bensemann seized on the possibilities of reductive caricature through a series of stylish, 1930s art deco inflected sketches – line drawings depicting visiting entertainers and local identities. One visitor with carefully exaggerated stage hair was the Russian opera singer Feodor Chaliapin, performing as a pointy-bearded Don Quixote.4 The mass of tight auburn hair belonging to Mary Glover, the English-born cosmetician and model married to poet Dennis Glover, was described by Bensemann with ultra-economy. A similarly audacious, streamlined treatment was given to Esther Levy’s sleek black hair, reduced to a trailing question mark.5

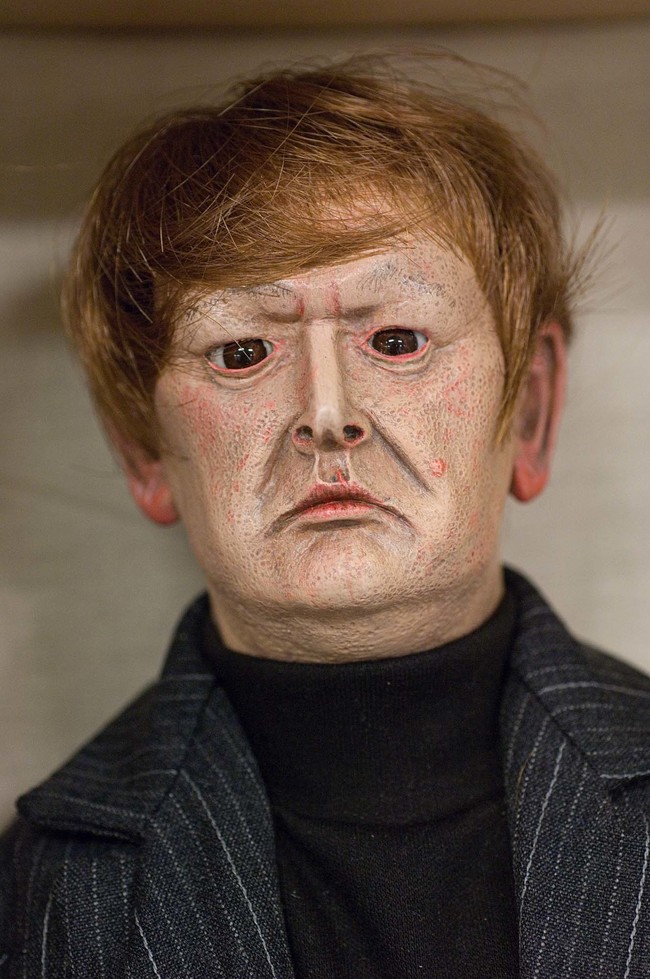

Peter Stichbury Mr Phil McEwan 2010. Acrylic on linen. Collection of Joanna and Pawel Grochowicz. Courtesy of Tracy Williams, New York; Michael Lett, Auckland; Gallery Baton, Seoul

Style and stylisation also establish the tone for two paradoxical photographic works, Yvonne Todd’s Ethlyn (2005) and Heather Straka’s Cindy (2009). Aligned to the seventeenth-century Dutch painting tradition of character studies known as tronies, rather than straight portraiture, these disquieting images each present a carefully-groomed young woman looking directly at the viewer. Ethlyn’s cascading blonde tresses appear transported from the 1970s (Todd discloses having spent a short time in her early career working in a wig shop – the influence seems evident). Cindy’s hair looks more this century: long, black and anime-inspired with flicked out ends. And yet, the meticulous styling of both contrasts with elements in the pictures that appear incongruous or wrong: Ethlyn’s mildewed white dress; the black gloves holding her guitar; Cindy’s cloud of brazen smoke testing the viewer.

Other links between hair, perfection and decay are manifest in Liyen Chong’s I am Here and There (2007), a heart and skeleton embroidered with her own hair in an exquisite meditation on mortality. Hair, we know, is imbued with corporeal associations. Alongside this embroidery are Chong’s Flying Oblique (2012), a photographic self-portrait-based work and William Blake’s equally lyrical ‘Then the Lord answered Job out of the whirlwind’ (Book of Job) (1825), illustrating a biblical reflection on suffering. Both are filled with swirling locks and dreamlike spirit, with Chong’s airborne hair a formal match to that of Blake’s universe maker, and almost equal in the big hair competition. A more literal face-off, however, exists in Patrick Pound’s Head (2005), a photograph picturing an ancient stone classical figure clutching her tresses. It’s also the ultimate metaphorical bad hair day: the hair remains, but her head and face are completely gone.

Pound’s image of hair, its owner long departed, is a reminder of a beard preserved at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, the longest ever recorded, grown by the Norwegian-American Hans Langseth and stretching to an incredible 5.33 metres.6 Langseth made the occasional sideshow appearance; his beard held the same kind of freak-show appeal as expressed in Christchurch illustrator Kennaway Henderson’s Man with Long White Beard (1920s). This stretches below his knees, and makes him a worthwhile candidate for pogonology, the serious study of beard wearing.

Liyen Chong Flying Oblique 2012. Archival inkjet print on Hahnemühle photo rag. Courtesy of the artist and Melanie Roger Gallery, Auckland

Enmeshed in this territory, historian Christopher Oldstone-Moore proposes that changing facial hairstyles, rather than revealing ‘fashion cycles’, present ‘instead slower, seismic shifts dictated by deeper social forces that shape and reshape ideals of manliness. Whenever masculinity is redefined, facial hairstyles change to suit.’7 Social forces highlighted in his study include political, religious and economic influences. Young beard growers in 1830s Paris, for example, were recognised as revolutionary romantics, who displayed greater risk through their hair expression than any 1980s punk.8 Within a few decades, however, the full beard was no longer associated with youthful idealism or a ‘calling card of social rebellion’. And by 1907, in James Balfour’s Portrait of Samuel Charles Farr, we find the full beard expressing a relaxed and stately confidence. Farr was a Christchurch architect whose achievements – apart from his flowing white whiskers – included designing many notable early public buildings and churches.9 (He is also credited with helping introduce the bumblebee to New Zealand.) An interesting contrast exists in Peter Stichbury’s Mr Phil McEwan (2010) whose equally snowy beard is studiously clipped. A long way from Gothic spires and bumblebees, he wears an eager intensity of expression and belongs more clearly to our own, more manic, times.10

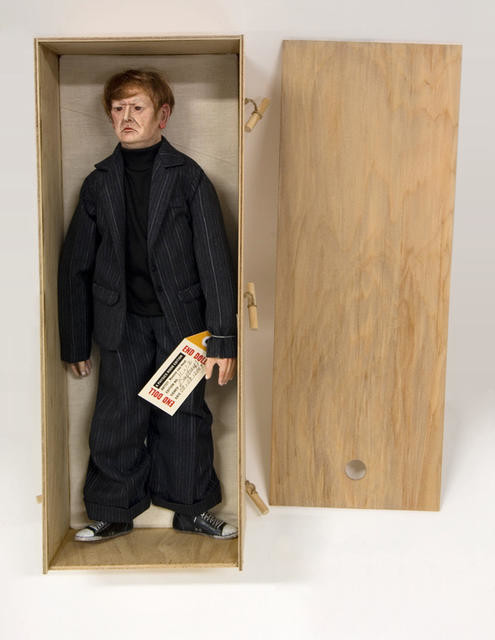

While changes in hair fashion can be studied and explained, some choices appear less explicable, and made for no good reason apart from the purposes of artful good humour. This quality resides in spades in Ronnie van Hout’s End Doll (2007) video and sculpture. Screen Ronnie, in massive curly black wig and puppet-like beard, explains himself carefully, blaming these ‘innocent looking’ production-line toys for his failed planet’s ills. The mini-Ronnie doll has hair like Trump’s – a crackpot style that now seems part of a global, dual art-and-life problem. But as is clear from looking at hair in history, the famous man’s hair only does what hair has always done. It communicates identity and provokes a response, while at the same time unwittingly revealing anxieties about ageing and death, and the desire to retain the impression of youth. Hair is linked to expression but also to basic human vulnerabilities. (Please remember the early warning about this being serious.)

Ronnie van Hout End Doll (detail) 2007. Mixed media. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2007