Some notes on movement in art

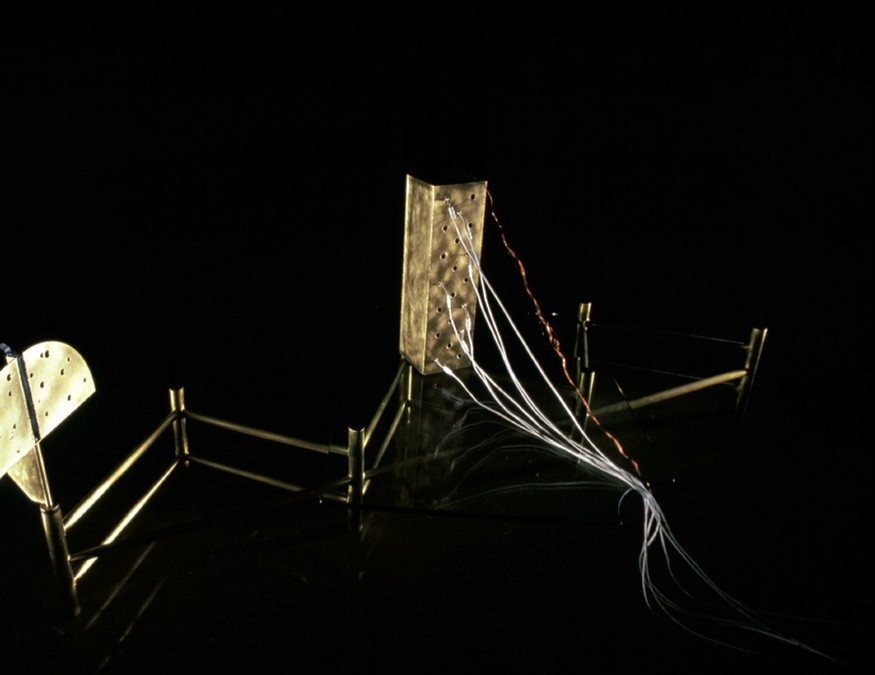

Andrew Drummond Sweet Place 2001. Glass, brass, wax, electrical system. Collection of the artist. Reproduced courtesy of the artist

Hanging from the ceiling in my infant son's room is a mobile. At rest, he seems to scarcely notice its suspended figures, but a quick breath brings them to life and, drawn to their gentle twirling, his face brightens and body tenses with a laugh.

His pre-verbal fascination provides only the most simple anecdotal evidence for our peculiar vulnerability to objects in motion, but the susceptibility of our attention to movement is deeply ingrained. A healthy capacity to track motion no doubt conferred some evolutionary advantage to a species both hunter and prey. And indeed, the neural pathways by which visual movement is cognitively processed are considerably older than those governing other aspects of visual perception, such as colour or pattern recognition. The sense of movement is fundamental to the way our brain constructs a coherent world from disparate physical sensations. So perhaps Len Lye and Laura Riding were correct to characterise it as ‘the earliest language', and one that ‘expresses nothing but the initial living connotations of life.' From infancy forward, motion compels attention like nothing else in the visual field, and is intimately connected to our physical being.

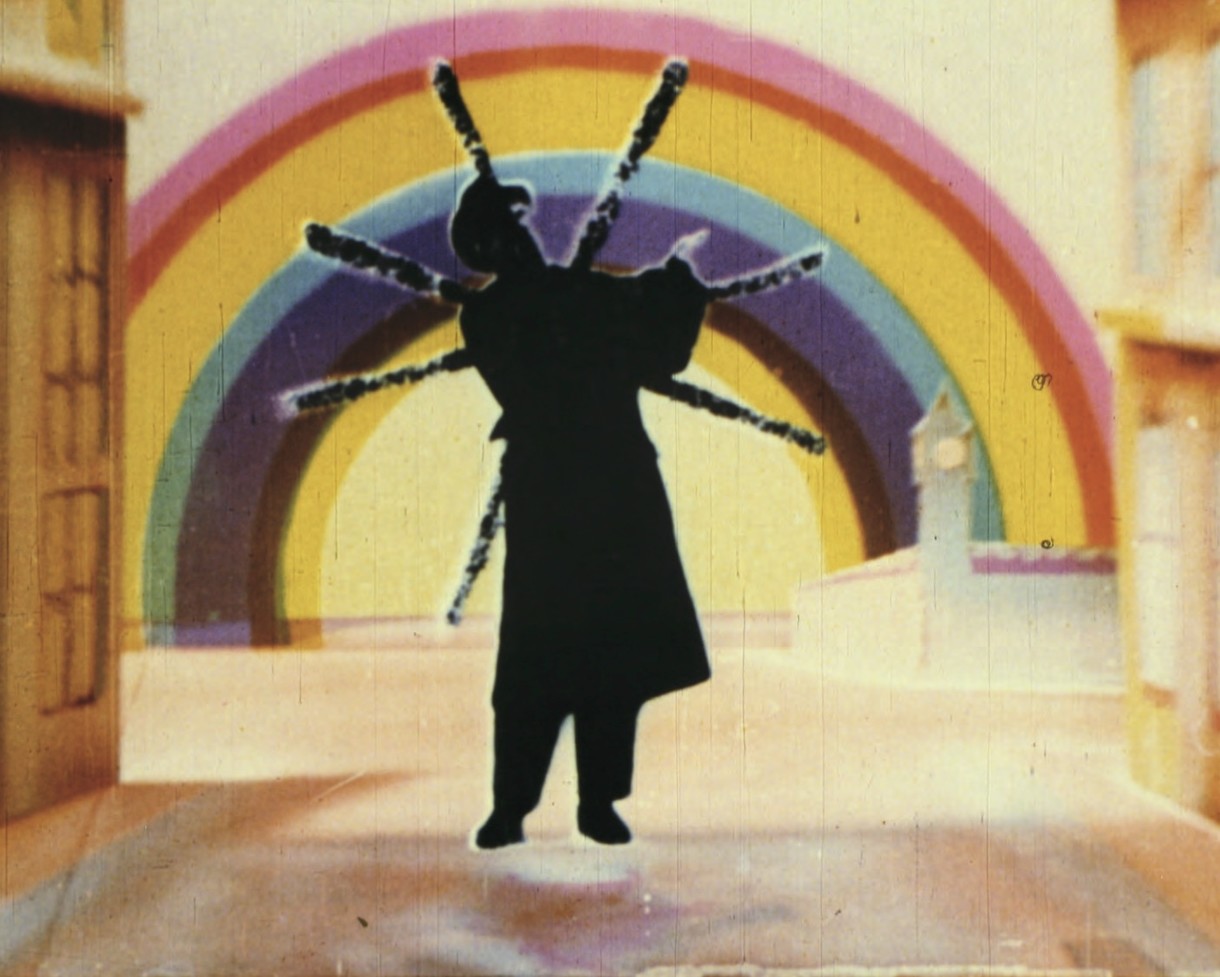

Perhaps this goes some way toward explaining the historical prevalence of a strong cultural desire to make things move. A recitation of this history of wonder-which might include the development of fireworks, mechanical automata and even cinema-is far beyond the scope of these brief notes. But we can at least glance toward the mid twentieth century, when artists began to incorporate movement into their practices, to shed light on some of the issues at stake. Following some famous, and largely isolated, experiments by Marcel Duchamp and Naum Gabo in the 1910s and 1920s, as well as Alexander Calder's invention of the mobile in 1931 (Duchamp coined the name), an explosion of moving, or kinetic, works of art occurred in the 1950s. Some of this work was created in reaction to the largely moribund lyrical abstraction choking Europe at the time. Seeing that the expression of subjective emotion in paint had become a spent force, bands of artists like Group Zero, Gruppo T, and GRAV (Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel) turned to movement as a way to give their art a life independent of the artist as controlling author. Prominent, if now largely forgotten, artists like Nicholas Schoffer looked to the new science of cybernetics for systems of programming feedback and response into sculptures attuned to a new technological society.

Others, like Jean Tinguely, parodied that society with junkyard contraptions that scrawled abstract pictures, or even destroyed themselves. Belgian artist Pol Bury investigated the destabilising effects of slowness, while in New York, the New Zealander Len Lye was spinning and shaking metal bands with frightening speed. Their works, like those of Brazilian Lygia Clark, explored motion in relation to our awareness of the physical body. For many artists, the experience of movement itself was a by-product of other concerns, but for Lye, the choreographed figure of motion and its impact on the body of the viewer was central, more important than the object itself. For fellow New Zealander Andrew Drummond, a 1976 visit to Lye, made while the younger artist was studying in Canada, was a formative encounter, and one that greatly reassured Lye that art in his native country had come far from where he had left it a half-century earlier.

Exposed to the accelerating boom and bust cycle of artistic fashion, kinetic art as an international 'style' had collapsed before the end of the 1960s, and its association with airports and corporate lobbies proved difficult to shake.

As a coherent movement, kinetic art had always been a construction of the galleries and museums promoting it. But issues regarding movement, the body, time, authorship and technology persisted as concerns within installation, video and performance practices. And they still persist today. As the mechanical means of making and programming movement in art have developed over recent years, kinetic practices have found place within the work of contemporary artists. Externalising the processes and movements of the body in sculpture has, in very different ways, become a concern of artists like Tim Hawkinson, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Wim Delvoye, and, in New Zealand, Andrew Drummond. For these artists, movement is less an end in itself than a medium to work with, and one that explores our congenital fascination with things that move in relation to what it means now to have a body.

Tyler Cann is curator, Len Lye at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. His recent projects include a retrospective of Lye's work at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, and co-editing a major new publication on the artist.