Power and Possibility

Dazzling Intersections Between Art and Light

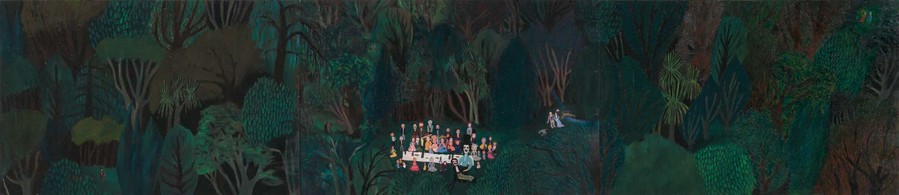

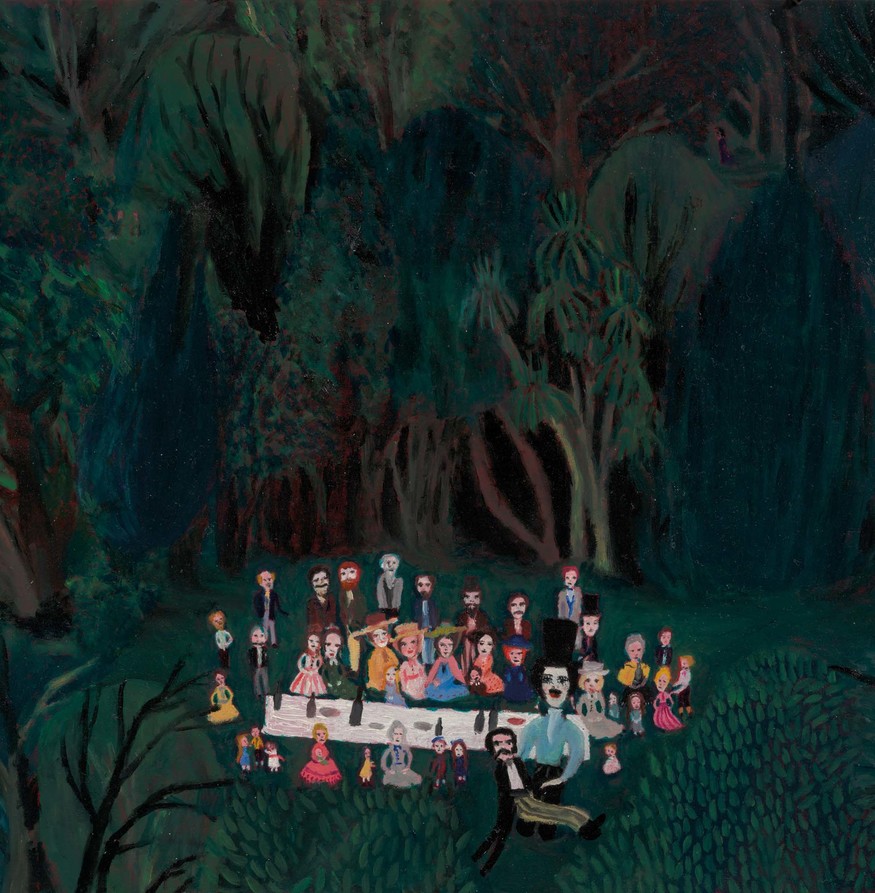

Saskia Leek Untitled 2000. Oil on board. Collection of the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, purchased 2000 with funds from the Dunedin Public Art Gallery Society

Jonathan Jones, art critic for the Guardian newspaper, described it as “a spectacle that displays the power and mystery of our planet”.1 Made more than forty years ago, Walter De Maria’s 1977 sculpture The Lightning Field remains one of the world’s most ambitious manifestations of light-based art.

Located in a remote area of the New Mexico desert, it consists of 400 polished stainless steel poles, spaced evenly across a one mile by one kilometre rectangular grid. The tips of the poles, which are solid and pointed, all finish at exactly the same height, with the length of the poles taking into account minor variations in the ground surface. The resulting horizontal grid is a monument to artistic tenacity and precision, and visitors still flock to walk through it and photograph it glittering against the morning or evening sky. Only a lucky few, though, have been present for the rare moments when the intrinsic promise of the work is fulfilled, when it tempts the lightning down from the sky to demonstrate the electrifying power and beauty of nature. The success of De Maria’s work rests not in flashy, on-the-hour pageantry, but in the enduring allure of expectation and possibility – a terrain also navigated by many of the artists included in Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū’s new exhibition of light-based works from the collection and beyond, Wheriko – Brilliant!

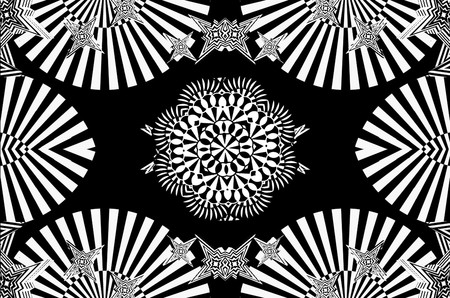

In te reo Māori, wheriko means to flash, gleam or sparkle; to be resplendent, impressive or brilliant, that English word referring to radiance that glitters or dazzles; and also mental keenness and ingenuity. All of those qualities are present within Te Pūtahitanga ō Rehua, a spellbinding animation by Reuben Paterson that digitally layers and rearranges his drawings into an oscillating, kaleidoscopic landscape. Inspired by traditional Māori references to water, stars, cleansing and transcendence – Rehua is the son of Ranginui (the sky father) and Papatūānuku (the earth mother) and associated in Tūhoe legend with the star Antares – Paterson relates the morphing black and white patterns to the changing energies and histories that have unfolded on the whenua of Aotearoa. The optical push-and-pull acknowledges the subjective, ambiguous nature of all perception; steering clear of a single, authoritative viewpoint in favour of a more playful and open-ended enquiry: “do you see what I see?” In Christchurch, Te Pūtahitanga ō Rehua is projected at a large scale onto a black wall coated with glitter, adding an extra dimension of volume and movement. It’s a material Paterson uses frequently in his work – though aware of its associations with children, crafting and showbiz, he points to its presence in nature; in the sparkling black sand on the beach at Piha where he grew up, in the shimmering sunlight on a breaking wave, and in the twinkle of stars in the night sky.

Daniel von Sturmer Electric Light (facts/figures/christchurch art gallery te puna o waiwhetū) 2017. Animated light installation. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of David and Robyn Newman, 2017

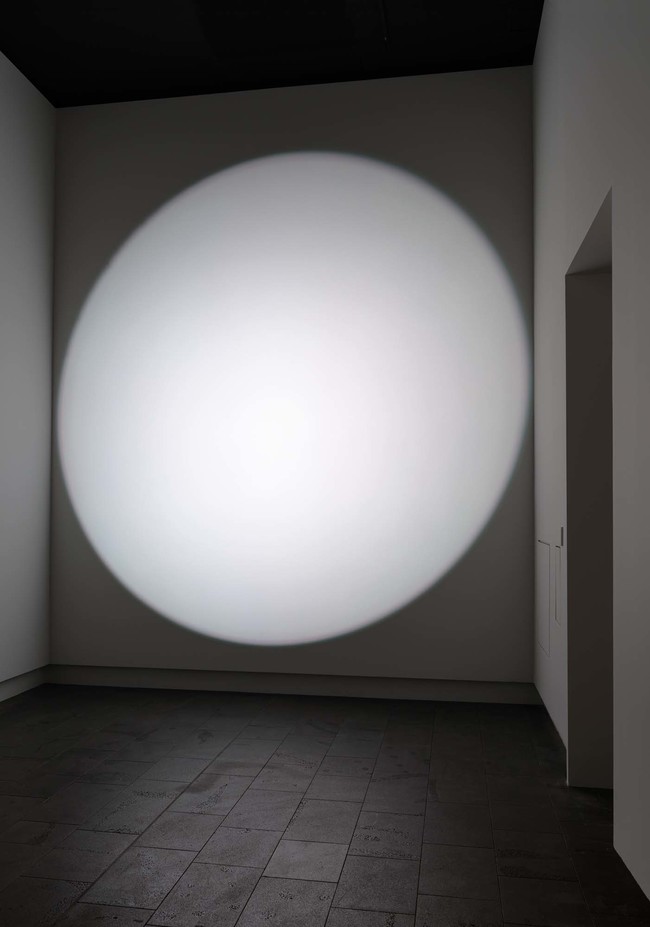

A recent work by Daniel von Sturmer uses light to reimagine the purpose of a gallery space, converting it from a backdrop for art to an active artistic collaborator. In Electric Light (facts/figures/christchurch art gallery te puna o waiwhetū), recently donated to the Gallery by generous supporters, a single robotic light scans the room in a sequence that has been minutely programmed by the artist. Drifting over floor and walls, its beam exposes and frames what von Sturmer calls “the features and facts” of the architecture – becoming a disembodied surrogate for our own gaze as it leads our attention around the room. It’s a little like turning off all the lights at home and shining a torch around – banal realities like the edge of a cupboard or a slightly asymmetrical line of floor tiles take on new significance when they are theatrically spotlit. Employing the light as not just a searching eye, but one with very human motivations, von Sturmer creates moments of humour and surprise: sending it back

to worry over physical details that appear out of place, or reframing them inside a series of projected shapes – a line, a square, a circle – as though attempting to puzzle out a narrative that might fit the assembled evidence. Effects that have become familiar through our experience of cinema are enlisted to trigger our expectations and associations; a lazy, speculative pan to set up the scene, a sudden shift in direction to follow the ‘action’, a spotlight that gradually fades from view to conclude the performance. On one level, it’s a caricature of the kind of looking we do in galleries, a grotesque enlargement of our viewing eye that slows and magnifies our observation, allowing us to focus on what was always there.

Saskia Leek Untitled (detail) 2000. Oil on board. Collection of the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, purchased 2000 with funds from the Dunedin Public Art Gallery Society

As Paul Cézanne observed, “sunlight is a thing that cannot be reproduced, it must be represented by something else – by colour.” 2 In a painting included in Wheriko – Brilliant! Saskia Leek goes one step further, representing it as a faint and faded memory, the temporary absence of darkness. Inspired by Bill Manhire’s ‘Picnic at Woodhaugh’, 3 a poem that was itself prompted by viewing a mid-nineteenth-century painting of the same name in the Toitū Otago Settlers Museum, Leek’s eccentrically horizontal canvas is a catalogue of translation and separation. In what must surely be one of the bleakest, funniest openers in New Zealand literature, Manhire writes:

In the half light of the Early Settlers Museum

there is a world of trees; they rise

on their roots to steal the sun.

But there is no sun.

Leek’s work, painted before she saw the 1863 original, presents the Southern forest picnic with a faithful intensity

that only increases its weirdness. Picked out from the encroaching murk of a shadowy forest, a group of ‘good folk’ stand as stiffly as the candles on a birthday cake. Transplanted from a foreign culture, they are out-of-place, fragile aliens, the white strip of their long table cloth at constant risk of being swallowed up by the woods, gobbled up by the night. It’s a distinctly non-heroic view of settler life – they are, as Manhire writes: “safely ashore, yet still at sea.”

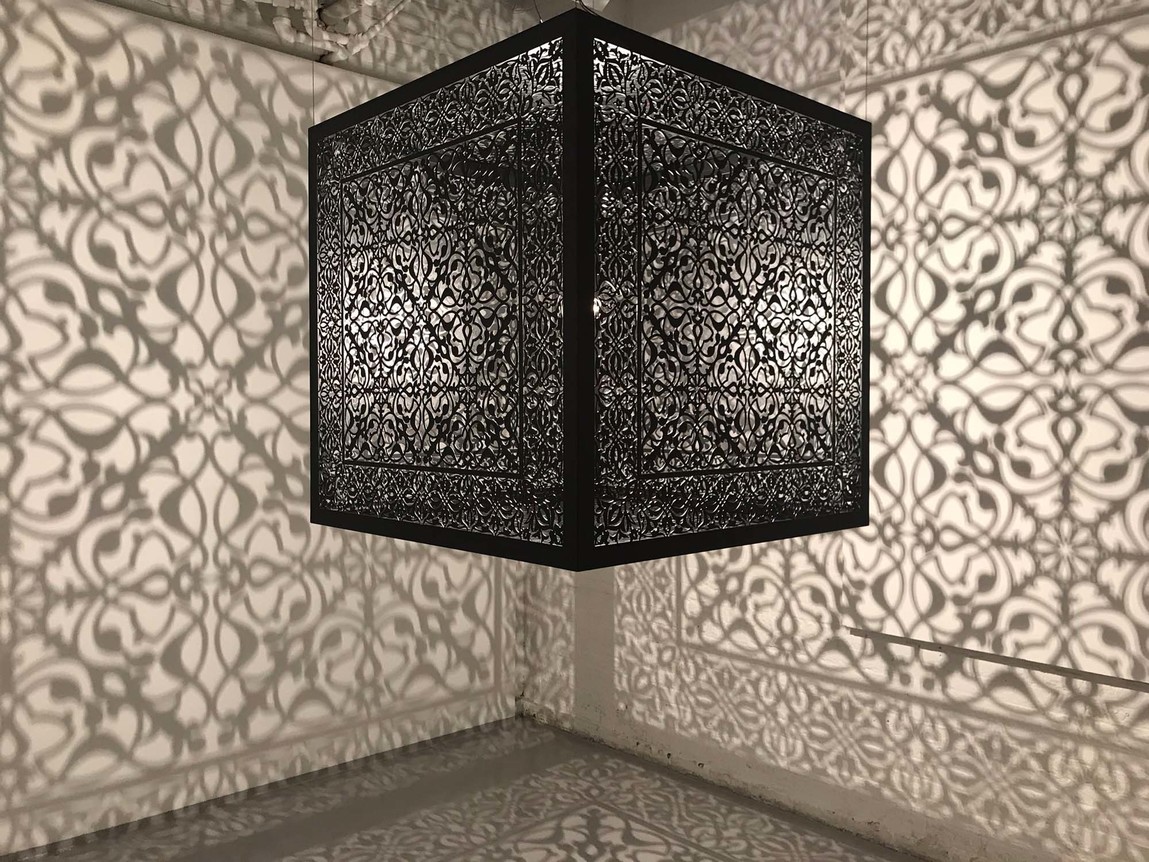

Anila Quayyum Agha Shimmering Mirage 2016. Lacquered steel and halogen bulb. Courtesy of Sundaram Tagore Gallery

Ernest Gillick Ex Tenebris Lux 1937. Bronze. Presented by R.E. McDougall, 1938. Reproduced courtesy of Norah B. Landells

Light and shadow are, of course, inextricably linked. Both are called upon, to spectacular and moving effect, in the suspended works of the Pakistani-American artist Anila Quayyum Agha. In Shimmering Mirage, a cube made from sheets of laser-cut steel is lit from within by a single halogen bulb, casting intricate, tessellated shadows onto the surrounding walls and floor. This visual duality between light and dark parallels the opposing emotions that prompted Agha to make the work. After travelling to her childhood home of Lahore to attend her son’s wedding, an occasion of great joy, she returned to the United States, only to receive “the dreaded phone call that every immigrant fears; my mother had died. I had just seen her, touched her, talked to her and now she was no more … As is the custom in Islam, she was buried within a day of her passing. There was no question of going; she was gone.” 4 Agha’s personal grief was multiplied by her awareness of another, communal bereavement endured by all those displaced by war or other disasters – the loss not only of loved ones, but of identities, cultures and homelands. The geometric patterns she cut into the steel are inspired by the ornately carved screens that feature in homes, gardens and mosques throughout Pakistan and many Middle Eastern countries, which filter out the bright sunlight while letting cooling air pass through. Her desire to share the beauty of Islamic art is tempered by the sense of yearning she felt as a young girl in Lahore, prevented by her gender from experiencing the full colour and grandeur of the mosques’ most sacred places. Ironically, now that she lives in America, Agha has found more acceptance as a woman than as a Muslim. For an artist fascinated by the “presumed opposites that are never quite so”, Agha’s choice of materials for this series of works is deliberately multi-layered. To Western eyes, black may appear funereal, and white is the colour most associated with weddings. In the Muslim community, however, white is the colour of the shroud in which a loved one is wrapped for burial. The steel walls of Shimmering Mirage enclose the light, but they also free it, and though the lacy forms appear fragile, Agha describes them as “resilient, hardy, and even stubborn in nature – like humans”.

Agha’s work reminds me of another sculpture, not represented in the exhibition, but which has been continually on public display since it arrived in Christchurch in 1938 – albeit viewable only through this gallery’s glass wall when it was closed following the 2010/11 earthquakes. Created in monumental bronze by the British sculptor Ernest Gillick, it depicts a young woman holding a lamp, looking down at the large book spread open in her lap. In the allegorical language Gillick was drawing upon, the lamp symbolises enlightenment, the book symbolises knowledge, and together they suggest the power of learning to vanquish ignorance. Three words in Latin carved into the sculpture’s base express a phrase that can be read, perhaps especially here and now, as an expression of hope and a call to action – Ex Tenebris Lux: from darkness, light.