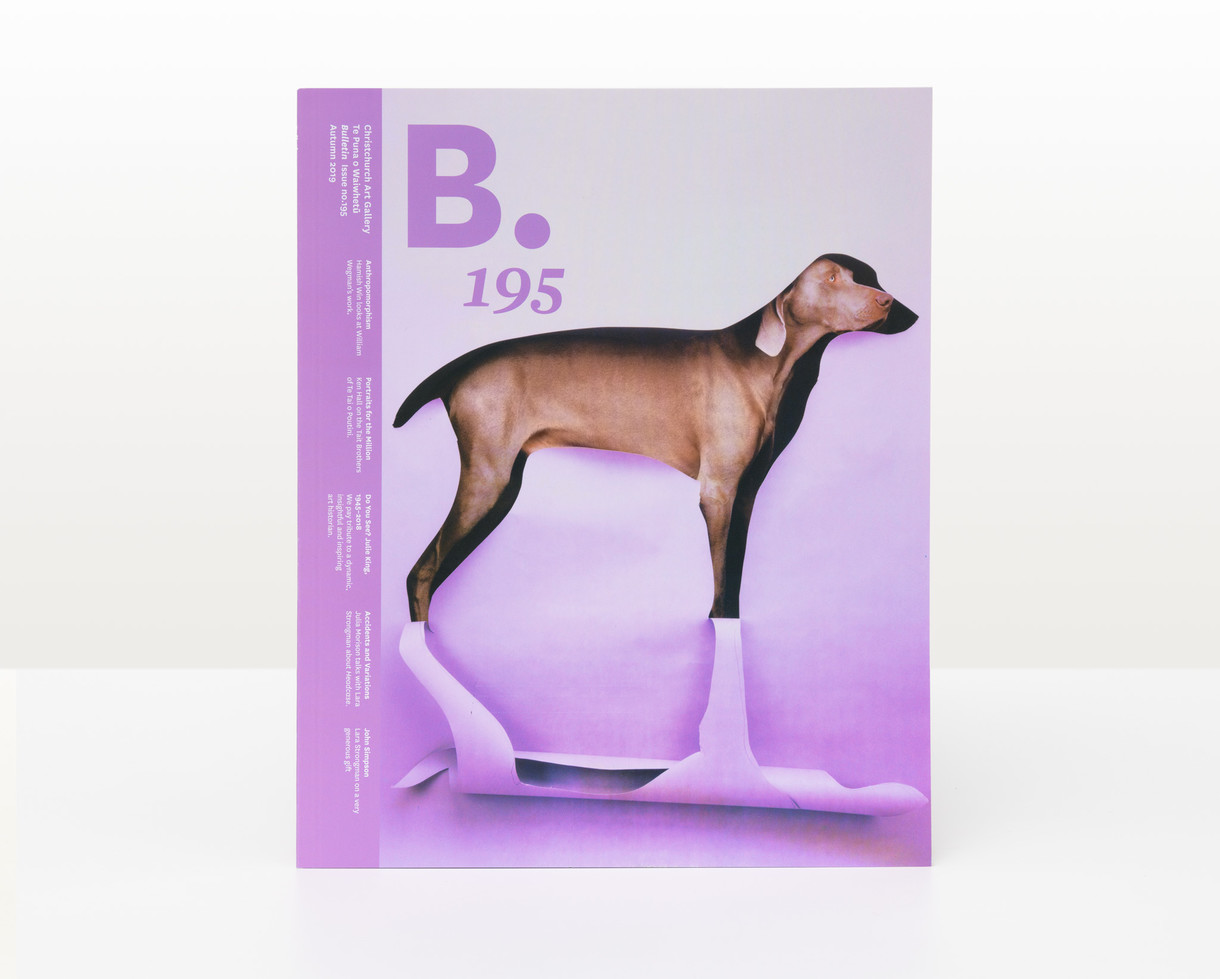

Julia Morison Headcase, 43 2015. Glazed stoneware. Courtesy of the artist

Accidents and Variations

Julia Morison talks to Lara Strongman about Headcase

Lara Strongman: Let’s talk about the process of making the works for this exhibition. Can you describe how you produced them?

Julia Morison: I’ve never actually made ceramics before. I read Edmund de Waal’s The Hare with Amber Eyes, which is about a netsuke set that is passed through several generations. De Waal is a ceramicist and he talks in this book about objects and porcelain in such a visceral way—basically he seduced me into picking up a ball of clay and playing with it. For a long time I haven’t had the use of my hands [because of arthritis], so I thought that playing with clay might actually help strengthen them.

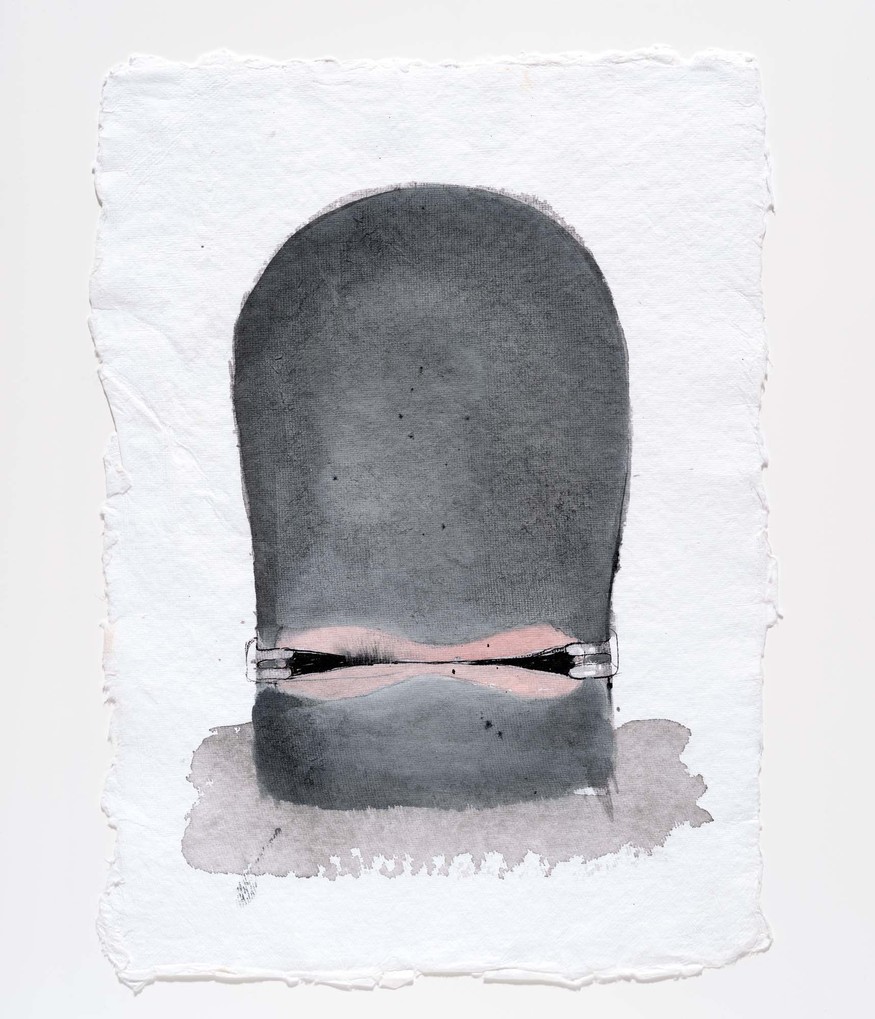

After the earthquakes, I bought a kiln from a neighbour who had been a tile decorator. Tatyanna Meharry borrowed it for her classes and in return gave me a few lessons. I started to enjoy the material, but at that point I wasn’t sure what I was going to do with it and was only making pinch pots. I can’t remember why I chose to make heads but when I did I decided to make a hundred of them—which was quite a leap. I tried different techniques, slab and coil, and the works I’ve made use both. I tried pouring too—slip casting—but my moulds weren’t good enough… but I think that’s more useful for repeating forms, to get each one perfectly the same, which wasn’t what I was after at all. From the start, I did want some unity within the heads, so made a mould, based on a wig form. I wanted the heads to be as non-specific as possible and genderless but more or less real scale. Some of them have become characters, and these may or may not end up on the shelves in this exhibition.

LS: Are they characters because they have facial features?

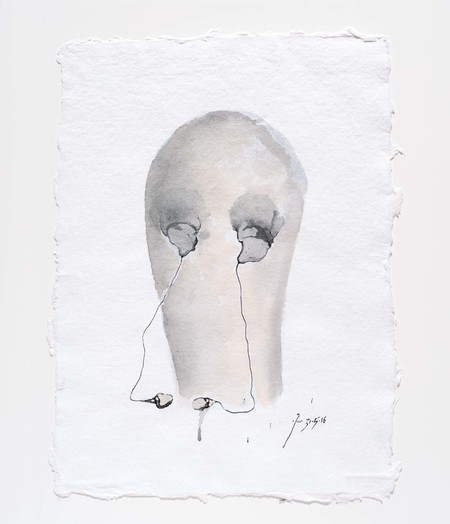

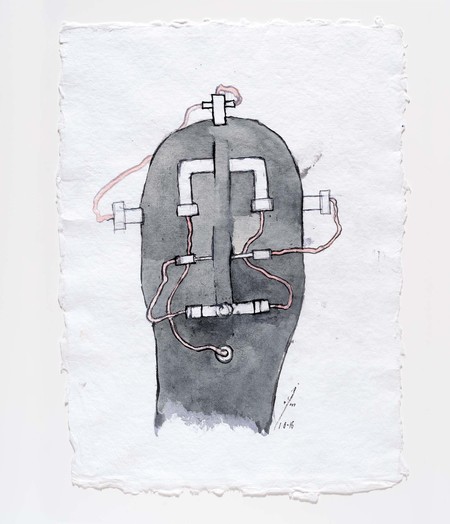

JM: I’ve concentrated on the holes or passages in the head: the eyes, ears, nose and mouth, and some have no passages at all, referring to skin or touch. These are our sensory apparatus. It’s something that’s been a bit of a preoccupation in earlier works. Right now I’m looking at you and in the first instance our interaction is through the head. I’m wondering what is going on inside your head as you’re maybe wondering what is going on inside mine. And I’m curious if we even see the same thing? I think those differences are fascinating. I’m partially deaf so you’re going to hear things that I won’t. What we pick up and don’t pick up will be different for each of us and what we put out is unique.

LS: We live in the same world but we all experience it in subtly different ways and we know from science and physics that the universe is vastly different from how we see it. These works come from the same mould but are completely different in the way they might interact with the world around them.

JM: Their facial features are, in most cases, like funnels or filters and some have accessories applied to them which could enhance or inhibit sensory data. Reduced to its essence, the head is a case that symbolically separates the self, the inside from context, the outside. I am also asking if we would experience the world differently if our sensory apparatus were other than it is.

Another layer is psychological; we have a lot of imaginative states based on the face and head in nightmares and dreams. Some people who have seen these works have found them disturbing and others have found them funny. Where I’ve concentrated on one feature, such as the nose for example, it feels more potent and a personality or a character type isn’t recognised.

Julia Morison Headcase, 21 2015. Glazed stoneware, paint, tacks. Courtesy of the artist

LS: What has been your process for thinking through all the variations?

JM: Sometimes I drew ideas, but these are just for memory jotters. It is difficult to translate from a two-dimensional drawing to a three-dimensional ceramic. Through the drawings I envisioned an outcome, but the result didn’t necessarily look how I might have imagined it. Sometimes I would begin with an idea and carry it through but at other times I would allow things to emerge as I worked. If the clay split or slumped, I would work with that.

LS: So you start with an outcome in mind but you might not actually end up with that outcome?

JM: For the project, I did set out to make a hundred yet there are actually 125, as I wanted some to edit out. Sometimes individual heads were determined from the start but at other times they evolved during the process of making. If an accident happens, I have to make something of that accident – I actually prefer when that happens.

LS: What do you like about the accident?

JM: It surprises me. I have to respond to and work with something that I haven’t envisaged. It is more exciting and I’m not fighting the material. It’s not that you lose control of it but the material wants to do its own thing. You lose it if you exert your will over it. It’s like painting – you have to work with it, not against it. Although you do learn techniques to get the effects you want. I started with porcelain which was idiotic in hindsight. Porcelain is a very difficult clay to use for what I’m doing as it quickly loses its plasticity. Cheryl Lucas told me about sculpture clay which has paper in it – it’s lighter and easier to work with compared with porcelain.

LS: Why did you want to make a hundred heads, and what’s the relationship of this work to the other ‘hundred’ works you’ve made, like the hundred-panel Golem, or 100-headless woman (1997)?

JM: Even when I was a student I would naturally make works in sets of ten: ten paintings, or ten drawings. Now it’s deliberate because it aligns with the structure of the ten Sephiroth of the Kabbalah. In regards to Material Evidence: 100-headless woman – well, where are the heads, and is there one or one hundred? In a way an ‘oeuvre’ is an artist’s self-portrait; so maybe they are all my heads and just one head. The “100-headless woman” comes from the Max Ernst work La femme 100 têtes, where ‘cent’ means a hundred but sounds like ‘sans’ – without. So the hundred are all without a head. Maybe Headcase responds to the void?

LS: So there’s a range of potential heads but they all come from your own.

JM: I can’t blame anyone else!

LS: Let’s talk about the Kabbalah, the Sephiroth; can you talk a little about your use of that system of knowledge as a starting point for making work? You’ve been using it as a background in your practice for a very long time. Can you go right back to the first time you decided to use it, and what you thought it would bring to your work?

JM: I became interested in it while at design school in the early seventies, but it didn’t reveal itself in my work back then. Immediately after art school, my work became increasingly abstract. And I had a rupture at a certain point; I lost interest in formal abstraction. Some people think that’s when I lost the plot, but producing endless permutations of formal abstract works, I would bore myself silly. That’s not to say I don’t love this genre of practice – I just didn’t have anything to add and lost interest in the modernist idea of making art devoid of meaning. I wanted to imbue my work with meaning and went overboard.

I was trying to understand and devise a visual language that would allow my work to be read without reference to text; to have meaning that I could determine – to some extent. I began with something extremely simple. I played around with writing the words god/dog repeatedly – I covered forty-eight sheets of semi-transparent paper with the words written forward, backward, in mirror writing and upside down according to a system. If you repeat something often enough it loses its meaning, which also interests me. And I loved the way ‘god’ and ‘dog’ merged the banal and the ideal. Then I coupled these two words with matter, dog shit and gold leaf. Expanding on this, I aligned ten different materials positioned within a hierarchy, from lead to transparency, heavy to light, feminine and masculine, in respect of the sefirothic system, alchemy and the writings of Carl Jung. I started making a work called Golem (the one in Te Papa) but I was getting into trouble. I was losing my way because I hadn’t done the groundwork. I went back and made a fifty-five- page drawing where I associated a shape or symbol to each of the materials. The work Vademecum (1986) takes the materials and symbols and combines each one with every other. Like a chart. I think that’s my design school training coming up – I used to love designing logos, I refer to the combinations of symbols as logos. I have made quite a few works using those materials, including Material Evidence: 100-headless woman.

The Kabbalah is a way of understanding the world through a highly visual language. It’s a tool, a filing system, a way of ordering information, and Kabbalists use it in highly personal or idiosyncratic ways. For me, it offers different viewpoints to look at things. Given that the system purports to assume “all and everything”, it’s not that constraining. I am trying to think when I stopped using it; well, I haven’t, but it may be less obvious now. For example, the seven hexagonal rooms in Headcase repeat the background geometry of the Sephirothic system. And clay is one of the ten materials I posit with a sefirah.

LS: I’m interested in the way that you deliberately impose limits on yourself. It’s similar to the Oulipo group of surrealists who made work by imposing constraints. Like Georges Perec, the writer who wrote the novel without an E in it.

JM: I love Perec! I saw an exhibition of his work at the Louvre, and it was surprisingly visual for a writer. His Life, A User’s Manual is a nauseating thing to read because it’s like an overly rich fruitcake. You get overwhelmed very quickly by the density of details. It’s fascinating to see how he worked it all out through charts – assigning a mineral, a period, a style, a personality to generate each room within the fictitious apartment building. His writing is extremely formal. I work in a similar way.

LS: What do limits and restraints bring to your process of making art?

JM: I need to go back to the start to talk about this. The design school I went to was industrial. The course was really there to support industrial design – they didn’t give a jot about your personal creative expression. In fact you didn’t even get a voice when it came to crit sessions – although everyone else did. What they were interested in was how the work would read. Just because you feel it or intend it, that’s not necessarily what people see in it.

At design school we worked to strict briefs, simulated client briefs. They were written on pink paper and we were told how many colours were permitted, scale etc. in each project. I loved that way of working because you were challenged to do something exciting within those constraints. I didn’t really intend to go to art school; I just did so badly at painting at design school, which was an extra-curricula subject. I never got a mark. I was zero zero zero the whole time and it really bothered me. I thought “There’s something deeply mysterious about this painting thing that I have to know about.” I loved it but I just couldn’t do it. In hindsight there was probably a different scenario going on – I wasn’t that bad (I can’t imagine giving anyone a zero). So I came down to Canterbury to do printmaking and painting. You had to specialise, and as I felt more comfortable with printmaking I chose painting. So I’m a reluctant painter or a reluctant artist.

LS: It’s very funny. Some people would say the difference between art and design is a brief.

JM: I work with a self-imposed brief or set of constraints. When I was at art school, Gopas and Sutton did their studio rounds, puffing on their pipes and giving very little, if any, direction. I was waiting for a brief which never came. “You can do anything you like.” It took me a long time to know what I wanted to do. I didn’t want to be a painter; I just wanted to know what painting was about, so the brief thing was something that I started to do for myself. I needed to put some kind of perimeter around myself in order to focus on small tasks. But now I think my work belies that. There is a structure there but I could apply it to stamp design, theatre design or public sculpture.

LS: In the past you’ve said you make things in relation to different kinds of opportunities. Which is perhaps another way of thinking about a brief. What limitation did the earthquakes put on your practice? What opportunity did you see in them?

JM: Well at the time I didn’t see any opportunity. It took a while to register what had happened because it was traumatic and not anticipated. But that’s part of my experience now, part of my life, all of our lives, our shared experience. Immediately after the quakes, whatever we had been doing beforehand seemed strangely irrelevant. At the time, I was painting. I was preparing for a show for Two Rooms, and physically struggling to do it. I was also procrastinating. The art shops were all closed but I am a bit of a hoarder so I was filling in time doodling with stuff I had here in the studio – but mindlessly. Phil Trusttum visited one day, and I knew the paintings weren’t going very well, and he was trying not to look. I pressured him “Phil, what do you think of these paintings?” “Oh Julia,” he said, “painting’s fucking difficult.” Oh thanks for that – just what I need. Then he turned around and said, “Well, what’s going on here? There’s your exhibition.” That was the start of the work Meet me on the other side. Those works were made with an abandonment that I hadn’t had before. I would love to have maintained that degree of ease in making.

LS: Did you ever think of leaving the city at that time?

JM: I really love my studio and its location in the central city. It’s a place that I could envisage happily living my time out but when everything shattered I did think I’d be forced to go. Christchurch is my home. Because I don’t come from a family with any interest in art, the people around me are my world and Christchurch is where I learned about art, found my voice and feel supported. I spent a decade in Europe in the 1990s, and didn’t intend to come back, but I did.

LS: Neither did I but here I am.

JM: That identifies us. It’s the lead in our feet or something.

The artist acknowledges the support of Creative New Zealand Arts Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa.

![Julia Morison: Head[case]](/media/cache/de/88/de88d73a69e40a8ec3368b62e2d68f52.jpg)