Daisy Osborn Rose Margaret Zeller c.1936. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

In Search of Rose Zeller

Enveloped in her dark brown coat and wearing an unconventional and distinctive striped shirt, Rose Zeller looks out from the canvas with an engaging and knowing smile. Painted around 1936 by her friend, fellow artist and teacher in craft and design, Daisy Osborn, it’s a rare view of an artist who, while scarcely remembered today, was an unconventional and respected figure during the interwar years.

Rose Zeller was the only child of immigrant parents: Hubert Zeller, a clock and watchmaker who was born in Mainz, Germany, and moved to London, and Sarah Eke from Norfolk, England. Married in London, the couple sailed to New Zealand on 12 June 1890. Hubert was granted naturalisation in 1892, and just five years later had established his own watchmaking business. Rose was born on 13 April 1891 in the family home at 325 Cashel Street, where she lived until shortly before her death. She was educated at Gloucester Street Public School (Christchurch East), attended Christchurch Girls’ High School in 1907, and, in 1909, registered as a student at the Canterbury College School of Art. It was not until 1927 that she began to exhibit, but she became known for her commitment to students and her creative approach to teaching arts and crafts at the Christchurch Technical College.

Very little has been written about Zeller,1 however, and what can be gleaned appears in seemingly unrelated fragments. A combination of random and intriguing leads coupled with numerous puzzling gaps defied a systematic examination, and prompted my search for the artist. Zeller died without any living relatives on 1 December 1975 at the age of 84, and most of what we know about her personal circumstances, birthdate and parentage comes from information that emerged in settling her estate, and from material which I consulted at National Archives.

It was Zeller’s writing that brought about my first exposure to the artist; her progressive views on children’s education, and on equality of opportunity for women artists gained wider coverage in the left-wing magazine, Woman Today. Her ‘To Teachers [Not all in Schools]’ raised fundamental questions about education and creativity that remain as relevant today as when they were first published in 1937:

When is it possible for a child, if he chooses, to sit and dream without other apparent consequences than a few naggings at home or at school, or a few impositions for failure to pass some specific test? Can his natural energy be expected to parade itself for inspection?

By harnessing energy to purpose, dreams are made manifest. Cathedrals, sculptures, bridges, music, are all dreams in manifestation. Not dreams turned sour little by little though first formed sweet, but plans for doing things encouraged and guided intelligently by ‘educators’….

The energy that in childhood dances through the fields all day and questions till the questioned one is tired, could surely build a paradise, if wisely guided and given constructive objects on which to satisfy itself.

Years later, the writer Elsie Locke remembered this passage, and reflected: “I would have read this twenty years before I began writing for children, and now I wonder what effect it had on me.”2

Woman Today promoted “Peace, Freedom, Progress, the Advancement of Women’s Rights, and Friendship with Women of all Nations”. Its simplified cover designs featuring images of the modern woman underlined its progressive aims. Run by an editorial committee in Wellington that included founding member Locke (then Freeman), it had numerous contributors, including occasional items by Jessie Mackay, Robin Hyde and Gloria Rawlinson.3 It covered a variety of topics including ‘Pioneer Women’, ‘Women of the Pacific’, ‘Maori Women of the North’, ‘Women under the Soviet Union’, ‘Women in Industry’, and Rose Margaret Zeller’s ‘Women Painters’.4

In this article, Zeller brought up issues that would be raised decades later by the Women’s Art Movement – the invisibility of female painters and their absence in histories of art:

In many current histories of art there is a notable absence of mention of early women painters. Indeed it is a rare occasion to see even one of their names in print, or to hear one mentioned even in the inmost of art circles. One might be led to infer that there were none, or that they were only worthy to be forgotten.

Underlining her point, she observed that “Many a serious student of art has never heard of them. Few seem to enquire if there were any, yet there were those who did work equal to that of many a living painter of note, and some who may be considered to have excelled.” Her observation that “the names of famous models are far better known to the world, than the fact that there were women of the past who were more than creditable artists”, would be reiterated in the Seventies.

Zeller’s article drew on Walter Shaw Sparrow’s Women Painters of the World, published in 1905. Among the illustrations was a self-portrait of Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1653), which prompted Zeller’s incisive comment that she “links her day to our own … she looks out from the canvas as vivid and alive as any educated intelligent woman painted today might look to generations as far ahead in time, as hers is gone by….”

Zeller discussed women’s participation in European art from the classical past to the present-day, noting their hostile reception by male artists and critics and “the opposition they met with in their determination to learn”. She held up the example of Laura Knight, an artist who had overcome humble beginnings to become, in 1929, the first woman artist to be made a Dame, and, in 1936, the first to be elected a member of the Royal Academy in London. Easily the most celebrated female artist in England, she had become famous in New Zealand, when her self portrait, which was exhibited in 1936 at the opening of the National Art Gallery in Wellington, was purchased anonymously and presented to the Gallery.

Looking to the future, she wryly concluded:

The day may be at hand when art is recognised for whatever quality it may possess apart from, and beyond by, whom it may have been accomplished. Women painters of the past along with those of the present and of the future may take their place in a recognised history of the whole story of art. Meanwhile one may smile and continue to wonder what would happen if women began to set themselves up as critics, and to require of men, that their work should show more femininity or to complain that it was not masculine enough?

Zeller’s own trajectory as a teacher and artist was marked by her commitment to progressive ideas, and highly individual paintings. As a student at the Canterbury College School of Art, she had concentrated on craft and design, supporting herself by winning the Applied Art Scholarship for craftwork in 1910 (worth £25) and a succession of annual scholarships. On completing her studies, she was appointed in 1915 as an instructor at the Dunedin School of Art where she worked until 1919.5 Ann Calhoun, in her pioneering book on women’s contribution to the Arts and Crafts movement, notes that on her return she taught elementary drawing, colour and design in the preparatory department prior to her appointment at the Christchurch Technical College. Florence Akins, a former student and teacher at Canterbury School of Art, recalled the support that her friend had given to “students from poorer families”.6 During the interwar years new opportunities were opening up for women, and training in arts and crafts offered girls and boys a creative pursuit that provided the prospect of employment, and of financial independence.

Rose Zeller Untitled c.1925. Oil on board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, presented by Henry Maitland Tomlinson

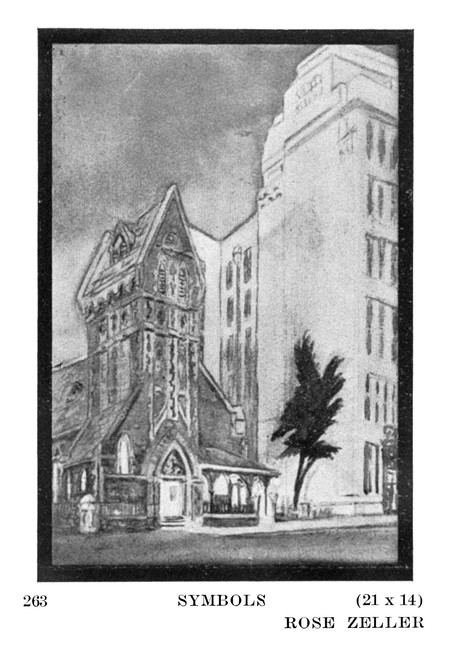

Rose Zeller Symbols 1936. Canterbury Society of Arts Catalogue

Zeller’s appointment at the Technical College is thought to have been in 1927, the same year she began to exhibit with the Canterbury Society of Arts (CSA). Her interest in painting went back to her time as a student, when she took landscape classes with Sydney Thompson. Several of her sketches are held in the collection of the Macmillan Brown Library, and an early work was recently included in the Christchurch Art Gallery exhibition Waiting for a Train, curated by Peter Vangioni. On display with old favourites from the collection such as Rata Lovell-Smith’s Hawkins (1933) and Rita Angus’s Cass (1936) were a number of less frequently exhibited works, including Zeller’s Untitled (c.1925). It is a striking image of an industrial site, and depicts a tunnel, a stationary steam engine and a lone man shovelling debris or coal. The complex construction by the entrance to the tunnel is closely observed and the whole scene captured in broad and bold brushstrokes. Its location is unrecorded, but attempts to identify it suggest the entrance to a coalmine on the West Coast – most probably Charming Creek, where coal-filled wagons were transported along a small bush railway to the railhead at Ngakawau.7 However, the glimpse of daylight visible at the end of the tunnel raises another possibility in the Cape Foulwind Railway, linked to a quarry at Cape Foulwind, which transported rocks to a breakwater in the Buller River.

In the exhibition, the painting is hung beside Doris Lusk’s Landscape, Overlooking Kaitawa, Waikaremoana (1948), a view of the extensive hydroelectric scheme at Kaitawa dwarfed by the surrounding mountains. Zeller shared not only Lusk’s interest in landscape, but her concern about the relationship between industrial development and the environment. During the 1930s, she wrote numerous letters to the press urging the preservation of “the beauties of our forests and natural scenery” in Westland, and prevention of “the needless desolation of forest country by dredging operations on the West Coast”.8

The scarcity of Zeller’s paintings (none were found in her house at the time of her death) belies their importance to her as a means of personal expression, and in providing an insight into the difficulties she confronted during her life on account of her German origins. Between 1927 and 1931 she showed around twenty-eight paintings at the annual exhibitions of the CSA. These included views of Auckland, Dunedin, and Sydney, including one of the harbour bridge under construction. But a change in mood is hinted at in 1936 in a painting reproduced in the CSA’s catalogue; Symbols depicts two buildings on Worcester Street: the Trinity Congregational Church, designed in French Gothic style by B.W. Mountfort, and Cecil Wood’s strikingly modern State Insurance Office, which had opened in August 1935. Symbols depend upon beliefs, and these may have signified faith juxtaposed with the commercial world and financial security. The lone macrocarpa tree would then become a representation of the inherent power of nature.9

From 1938 she exhibited only a few paintings, and these include Peace and Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament in 1941, Prayer in 1942, and Closed Door and Old Old Steeple in 1944. Little Church, which was shown in 1945, was her final exhibit.

Zeller was only a girl when war was declared on Germany in 1914, and the paintings she made during World War II may be seen as an expression of faith and despair. During World War I, German residents in New Zealand had been interned or required to report regularly to authorities. As war persisted and casualties increased on both sides, Germans were treated with fear and suspicion, and shops and businesses, including Hallensteins, attacked. An untitled work from around 1945 recently added to the Gallery’s collection is a mystical and prophetic image inspired perhaps by William Blake, in which a figure ascends above a host of aeroplanes flying across the harbour. A dead tree dominates the foreground of the scene, while a bizarre machine tramples through the undergrowth and brings destruction.

Rose Zeller Untitled c.1945. Watercolour. Rose Zeller Archive, box 2, Robert and Barbara Stewart Library and Archives, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Wawiehtū

A friend, Henry Maitland Tomlinson, who donated the painting to Christchurch Art Gallery, recalled that Zeller became unwell in the mid-1940s. Although she kept in contact and awarded prizes to students at the Technical School during the 1950s, she led an increasingly solitary life over the following years. Her death on 1 December 1975 prompted an article, ‘Portrait of a city character’, which appeared in the Star. By that time she had become known as a lovable eccentric rather than as an artist, but to those who had known her she remained a visionary, who was ahead of her of her time. Although her later years were solitary, the fact that she had touched many people’s lives was evident at her funeral, which was attended by teachers, artists, ecologists, shopkeepers and former pupils.10

The achievement of women artists in Canterbury during the interwar years would gain recognition in the landscape paintings of Rose Zeller’s younger contemporaries Rata Lovell-Smith, Rita Angus, Louise Henderson, Olivia Spencer Bower and Evelyn Page. Zeller’s own relatively humble beginnings, German origins, and the experience of living through World War I followed by the onset of fascism and the outbreak of World War II undermined everything. Zeller was a fascinating but elusive figure. Through her teaching, painting, writing and progressive ideas, she succeeded in making a positive contribution to society, challenging people to think, look and find their own way.