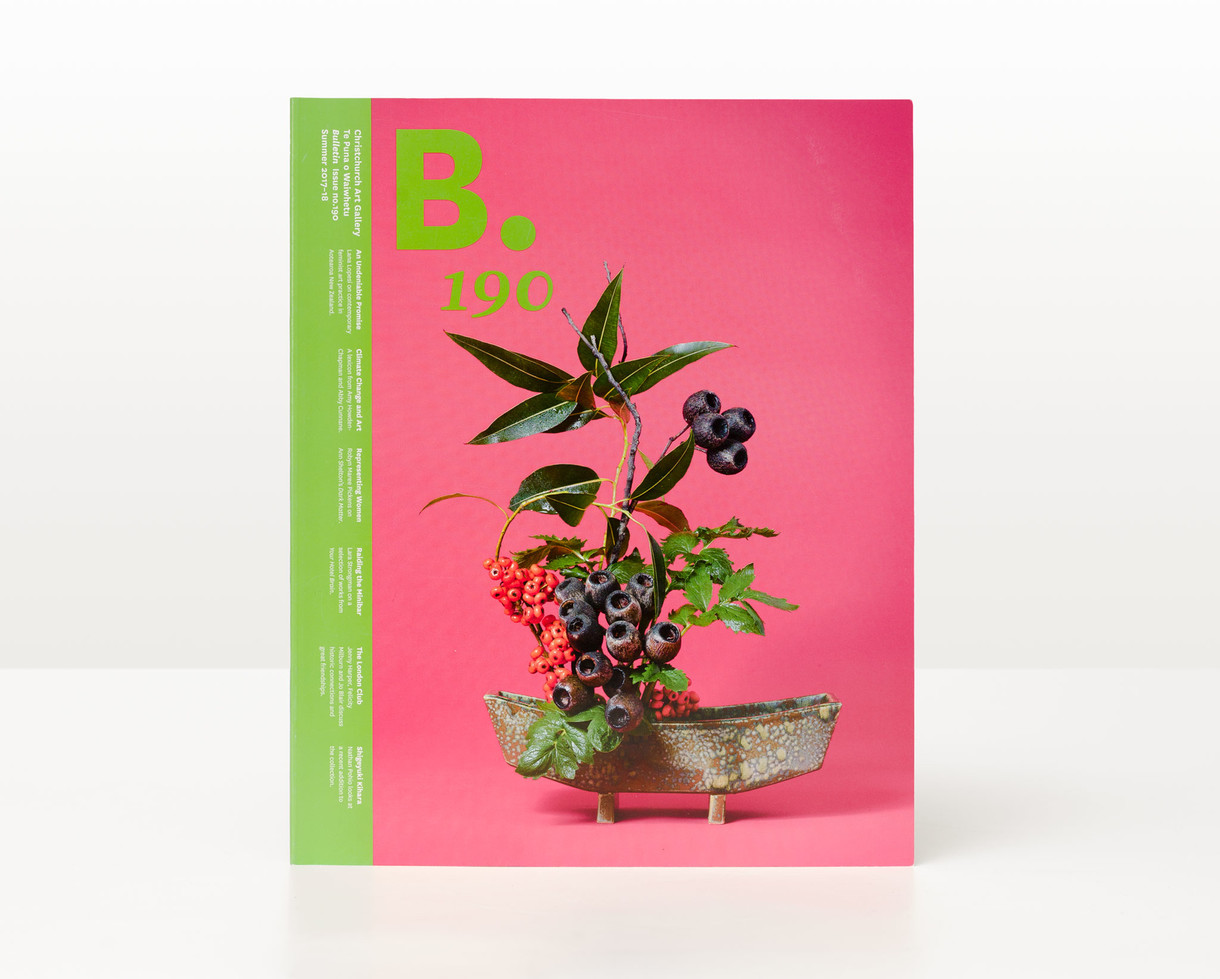

Shigeyuki Kihara

Shigeyuki Kihara Roman Catholic Church, Apia 2013. C-type print. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2017

Behind the work of Auckland-based artist Shigeyuki Kihara lies a vigorous research ethic that falls into complex alignment with her cultural, political and gender identities.

Born to a Japanese father and Samoan mother on Upolo in 1975, Kihara was raised in Samoa, Japan and Indonesia before moving to Wellington to study at age fifteen. Describing herself as a transgender person of the Pacific experience, she is Fa’afafine – a person within Samoan society who ‘does in the manner of a woman’,1 who exists in the va. The va can be understood as a space of betweenness, or as Albert Wendt writes ‘Not a space that separates but relates, that holds separate entities and things together in the Unity-that-is-All, the space that is context, giving meaning to things.’2 As happens in colonised nations, indigenous structures become compromised; and with the introduction of Christianity to Samoa the traditional place of Fa’afafine was quickly discouraged.

These experiences give Kihara a rich, multicultural lens through which to view the world; the dualities and nuance in her experience produce complex works which use art historical references to facilitate powerful critiques of colonial history.

This is particularly evident in one of two works recently purchased by the Gallery, Roman Catholic Church, Apia (2013). Having discovered Thomas Andrew’s 1866 photograph, A Samoan Half Caste, Kihara developed a persona named Salome – after the biblical figure who, she notes, influenced politics through dance. In Roman Catholic Church, Apia we see Salome, dressed in black Victorian mourning clothes, posed to consider the effects of colonialism and the church upon Samoan culture. As she performs a quiet stillness in the heavily damaged vastness of the Roman Catholic Church, a kind of white noise feedback happens within the frame. The image becomes all the more expressive when we discover that wearing the Victorian dress is described by the artist as a violence or ‘bondage’ against the body.3 But juxtaposed against this political expressionism is a deep sense of tenderness as the artist also clearly recognises what the destruction of the church means to a community she loves.

Shigeyuki Kihara After Tsunami Galu Afi, Lalomanu 2013. C-type print. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2017

Along with After Tsunami Galu Afi, Lalomanu (2013), which was also purchased by the Gallery, Kihara’s Roman Catholic Church, Apia forms part of the artist’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? series, which comprises twenty-one works. Named after Paul Gauguin’s last major work in 1897, the series illustrates an idea far from the painter’s idyll on the course of life; rather the artist pays witness to Samoa in the aftermath of 2012’s Cyclone Evan. Throughout the series, Salome is positioned with her back or profile to the viewer, guiding our gaze towards the landscape, environment, monuments and architecture and opening a space for us to enter. It’s reminiscent of Holly Hunter in The Piano, but also of another cinematic moment, and genre referenced many times by generations of the LGBT+ communities – the final scene in Gone with the Wind as Vivien Leigh’s Scarlet O’Hara contemplates the end of one day and the potential of another.

As much as we are Salome’s guest, she controls our gaze; we are not witness to persons in states of shock or trauma, nor are we invited to panoramas of the land subjugated by the disparaging twenty-first-century phenomena of ‘disaster porn’. Instead she performs in a quiet way, slowing things down, and letting the juxtaposition of the dress, the landscape and architecture fill each image with a complex range of senses, ideas and emotions.