Your Hotel Brain

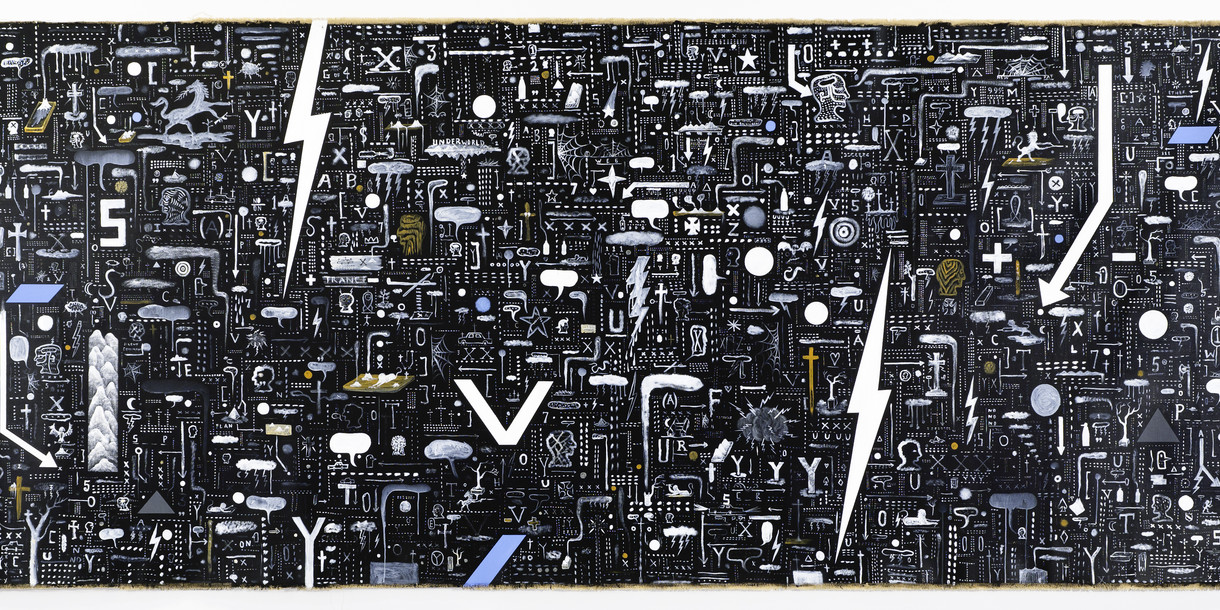

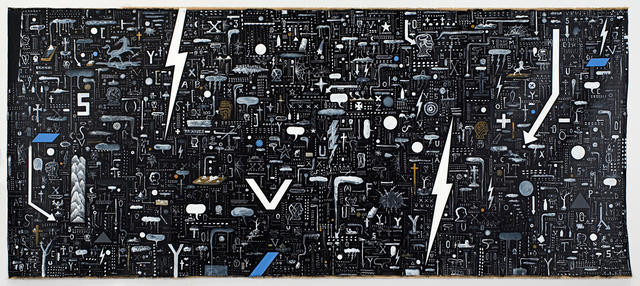

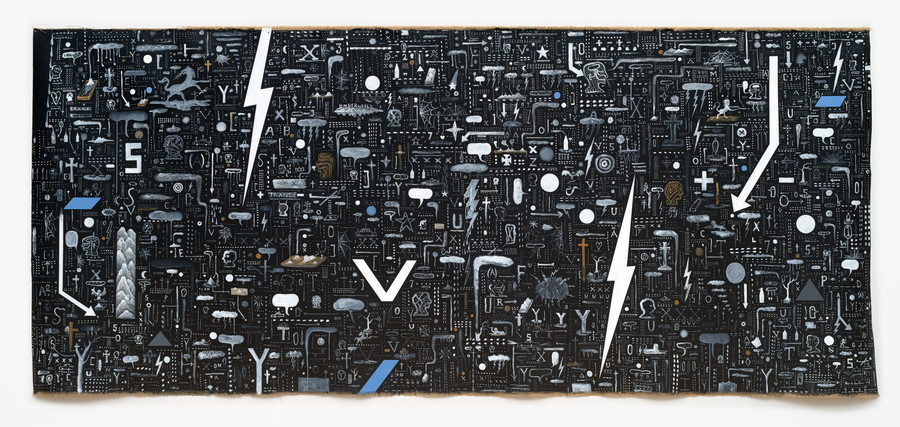

Tony de Lautour Underworld 2 2006. Acrylic on unstretched canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased by the Friends of Christchurch Art Gallery 2007

We recently opened a new collection-based exhibition, Your Hotel Brain. Curated by Lara Strongman, it focuses on the cohort of New Zealand artists who came to national – and in some cases international – prominence in the 1990s. The title of the exhibition is a phrase drawn from Don DeLillo’s epic novel, Underworld, published in 1997. It gestures towards the way that pieces of information float through your mind, checking in and out, everything demanding attention, everything happening all at once – a metaphor for postmodernism in the 1990s and for the increasing slippage of context in the digital era. The 1990s were a time of great social and cultural change in Aotearoa New Zealand, set against a broader backdrop of globalisation and the rise of digital technologies. Artists, as ever, registered these cultural shifts early. We asked a number of people who were working in the arts at the time to recall their experiences of the 1990s.

Tessa Laird

Lecturer in critical and theoretical studies at the Victorian College of the Arts

Over the past few years I’ve been asked to comment on the nineties numerous times, and it always unnerves me. I hear ‘the nineties’ glibly cited by art students who were barely out of nappies by Y2K, as though that decade’s mere utterance conjured a specific aesthetic. I understand this desire for casual connaissance of eras; I spent the entire eighties trying to relive the sixties and seventies, even though I wasn’t around for the former and was a rather green observer of the latter. But the nineties? How could that varied decade become fodder for ironic categorisation or arch summation?

What I remember most about the nineties artworld in Auckland was a long overdue efflorescence of diversity. A new generation of Māori artists were making work that was political and intellectual, from Lisa Reihana’s energetic animated films, to Peter Robinson’s clever play with racist ideology, to Michael Parekowhai’s beautifully conceived sculptures sporting his sister Cushla’s witticisms for titles. John Pule combined Niuean hiapo designs with his own poetry on canvas, Ani O’Neill met high modernism with Cook Islands traditions, and Jim Vivieaere and Albert Refiti emerged as important thinkers in the Pacific art world. New Zealand artists of Asian descent, including Denise Kum and Yuk King Tan, started making work from their own unique cultural perspectives. And feminism and sexuality outside of hetero-normativity was huge, witness the controversial One Hundred and Fifty Ways of Loving show at Artspace in 1994.

Two other tendencies stand out to me, perhaps somewhat oppositional to each other: the Hangover scene, which I name after the show curated by Lara Strongman and Robert Leonard, and the techno-utopians, nurtured by Sound/Watch and other events at Artspace under Lara Bowen. Lara’s partner Mike Hodgson was pivotal in this world, and it featured the maverick sexual CD-ROM romps of Terrence Handscomb, along with the goofier interactivity of Sean Kerr. Sound art legend Phil Dadson was this world’s patron saint, and the newly minted internet was its holy grail. The Hangover crowd, on the other hand, was into kitsch and grunge, the handmade and the half-assed. Judy Darragh, with her leopard prints, fake vomit patches and gold dildos, was the social glue, while Ronnie van Hout’s self-deprecating self-portraiture, Saskia Leek’s bewitchingly childish paintings, and Gwyn Porter’s untamable art writing all played a part.

Like the Hangover crowd I believed in the DIY aesthetic of the zine, which grew into the publication of a real grownup magazine (Monica) and then an un-grownup one (LOG Illustrated). Giovanni Intra and others like the eternal trickster Daniel Malone turned DIY into the legendary Teststrip Gallery. Giovanni will always be synonymous with the nineties, as he lived only a few years into the new millennium. What I wouldn’t give to read his summation of the decade he helped make so interesting.

Blair French

Director curatorial and digital, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

My 1990s were spent working in a variety of locations in New Zealand, the UK and Australia. These were places with very different art scenes and immediate pressing societal urgencies and cultural legacies. Nevertheless a commonality stood out in the willing confrontations with history, particularly the colonial project of modernity and its legacies of oppression and disenfranchisement taking place in much of the keenest art and theory of the time. What I gleaned through my early 1990 and ’91 engagements with the work of then emerging artists and peers negotiating this territory – some Māori, many not – of my generation provided some tentative markers for all my subsequent curatorial work.

Returning after a few years working in the eviscerated heart of the industrial revolution and former colonial engine room that was the North of England, spending much time with work emerging from diasporic communities taking on the impact of Empire in new ways, the newly sharpened finish and intellectual acuity of work in New Zealand immediately struck me. This work of the mid nineties appeared custom made for curatorial provocations yet could easily pull the rug out from under our sloppy propositions. Artists were honing our curatorial practice, not just with regard to their work but also to that forming the immediate art histories it emerged from.

Then over the water it was the artists – many but not all of them Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander – working with lens technologies whose work most struck me on arrival in ’95. These were artists dragging elided and often violent histories into the present through the appropriation of a tool of colonial investigation and oppression. Curatorial practice had to become one of acknowledgment and of opening spaces one had nominal control over to these critical artistic acts. And I’d argue that the matters of culture, language, historical recognition and sovereignty that sat central to the art scenes I worked in through the nineties remain crystal clear and urgent in our contemporary now.

Philip Matthews

Journalist and movie critic

I remember the second or third time I saw Reservoir Dogs was at the Paramount in Wellington when they put on a media screening and someone who was more of a published movie critic than I was then, a guy about the same age who I had known at university, walked in quoting the dialogue. It’s hard now to get our heads around how much of a big deal that movie was. You could say, a little pompously, that for our generation it mattered like Bonnie and Clyde or A Bout de Souffle did for earlier ones. It said that old rules don’t apply. You could include things that other people said you could not include. Everything was up for discussion. Who decided that the types of guys you would normally see in movies like GoodFellas or Thief wouldn’t sit around talking about Madonna songs? There was a freedom to the post-modernism that Quentin Tarantino embodied and put on screen that was squandered pretty fast, by imitators and maybe himself. I don’t know if the same thing happened the same way in the artworld, but works by Peter Robinson, Saskia Leek and Tony de Lautour in Your Hotel Brain take me back to that exhilarating moment.

Delaney Davidson

Musician and writer

It was the goddamn cocksuckin motherfuckin nineties and the nighttime walking took over. Terrified of wasted time. The world was disappearing. The shadows gave things substance. Extra depth. Consolidated form and distance into something immediate. Acid ate into the plates. Creating shadows. Ferric chloride and nitric acid. 2 parts FeCl3 to 2 parts water and 1 part nitric to 3 parts water. The results were rich deep and heavy. Foul bite. Expressive wipe. The best was under the trees. Looking though the parks. That was until I went out to learn how to mix paint with Richard Clemens. The train ride was about three hours, Melbourne to Colac. We spent the days mixing up combos of Burnt Umber, Ultramarine, Zinc White and Naples Yellow. You could get almost darker than black. The depth and weight was infinitely adjustable. I spent the train ride home staring out the window with the curtain wrapped round my head, trying to see into the night and how minimal light spelled out the lay of the land. The old techniques. Fuck video installation. Fuck sneaking to get some forbidden landscape fix. This was the end of the century. Everything and anything goes. Fin de siècle motherfuckers. Fin de siècle.

Christina Barton

Writer, curator, art historian and director of Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi, Victoria University of Wellington

Why aren’t the nineties clearer to me? Book-ended by my transition from Auckland to Wellington at the beginning of 1992 and the opening of Victoria University’s Adam Art Gallery at the end of 1999, they were crucial years in my development as a curator and art historian. But perhaps the births of my daughters in 1994 and 1999 are good reason for faulty memory: it was a busy time. What I do recall of the decade were the ambitious, curatorially driven exhibitions designed to speak back to Wystan Curnow’s and John McCormack’s teasing proposition of art as a ‘European idea’. By packaging together and touring regional, bicultural and counter-national groupings of artists, Headlands, Cultural Safety, Toi Toi Toi, The World Over, and the trans-Tasman project Close Quarters (with which I was involved), all set out to take New Zealand art offshore, proving we were less intimidated by our location at the ‘bottom’ of the world.

This was a process of global positioning, when the idea of ‘New Zealand art’ still had some purchase. Comparing then and now, what strikes me is the archaic nature of the technology we worked with: letters, landlines and fax machines; this was an unimaginable time before the internet. Yes, the ‘digital revolution’ had begun, and I remember all the fuss and then the fizz around what would happen if the machines couldn’t deal with the new millennium. But I recall writing faxes to Joseph Kosuth in New York and Rome in 1999, after he agreed to undertake the Adam Art Gallery’s first international project; I travelled to visit him in his studio in Rome in October of that year with a cardboard model of the gallery in my hand-luggage. I also have a visual memory of the art history department’s fax machine spouting paper that had printed overnight with the latest missive from Boyd Webb in London when Jenny Harper was doing her big project with him (1998). Perhaps I was a slow adopter, but the transition was not instantaneous, even though Victoria University was at the cutting edge of the new technology and by the end of the decade email was beginning to make communication quicker and easier. I didn’t get a cell phone until 2003 nor a smartphone until the early 2010s. When did we start googling everything? It certainly wasn’t in the 1990s.

Gwyn Porter

Writer, editor and educator

This is difficult to write about because the nineties cleanly bracket my twenties.

I was a curator then, a new entity in a particular sense, and writing – corresponding to the form of the work – was part of my adopted duty of care.

Life is a matter of constant adoption and re-adoption.

Then, we called each other on the phone and arranged to meet.

The only people with mobile phones were in advertising, film, or drug dealers.

Email attachments did not come in until late in the decade.

People did not customarily hug each other upon meeting or leaving.

Much of my time was spent not-quite-consciously trying to work out a language for existing in an intensely neoliberalising system.

It was clear we were in a low-rent patriarchal and post-colonial place, but it was hard to talk about.

An aesthetics of precarity was summoned by a way of life.

Our criticality felt very immature, but vital. Representation was suspect. Indeterminancy, complexity were not.

The image became political. Some read theory and radical literature long and hard and joyously. Film was electric.

All our decisions were based on what was interesting at the expense of a stability we did not value.

A great many para-chemical risks were taken with bodies, minds and spirits. With selves, relationships, subjectivity, movement, language – real and para-chemistry.

Emotions came off badly but no one wanted to know about it.

Dissonance, derangement, dilating sense. Dissensuality needs teeth.

‘Do you like your teeth?’ I was asked at the end of the decade

Being present at the point when things emerge requires constant movement.

It was not a nice time. But I still admire the enthusiasms that flared between us. Not that many would know what they are now.