Collections Matter

Since late 2006 when I started as director of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, I’ve written several times about our art collections in Bulletin forewords. Given their centrality to our daily work and our reason for being, this is unsurprising. So it’s good news that we’re focusing on collections in this edition of our quarterly journal.

For me it is another chance to write of the importance of collecting art in Christchurch in advance of the Gallery’s re-opening, and to remind ourselves of the history of our collections. It’s also a chance to focus our community of supporters and readers on the purposes of our collections—to argue strongly for the benefits an art gallery brings to a city and its people—and to recall the visual pleasure and stimulation our collections give and will continue to give.

This is also an opportunity to express some concerns I have for the future funding of this gallery’s collection. These concerns are not new and have been expressed in differing ways by my predecessors and others associated with collecting for Christchurch’s public art gallery over the last eighty years. For, while the collections are our responsibility and while their care and presentation are foundational Gallery tasks, their broader social purposes are not always grasped.

Petrus van der Velden The Dutch funeral 1875. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gifted by Henry Charles Drury van Asch 1932

HISTORY OF OUR COLLECTION

Christchurch citizens seem proud of—but perhaps a little complacent—about their cultural history. However it’s worth noting that this city established a public art gallery only in 1932 with the opening of our predecessor institution, the Robert McDougall Art Gallery. 1 The city’s call for financial support for a new facility at this time was prompted most immediately by the Jamieson bequest 2 in 1927 and initially, 160 British and New Zealand paintings and sculptures were displayed. Apart from the Jamieson bequest, these were largely from the Canterbury Society of Arts (now the Centre of Contemporary Art or CoCA) which, in its early incarnation, had amassed works by living British and New Zealand artists.

The city’s collections have been strengthened regularly by donors of diverse origin, with a range of historical works in the collection relating to where people (or their forebears) came from and where they travelled. Works of British origin are certainly more numerous, but the Dutch gain ascendancy in terms of quality. In 1932 the Van Asch family, who invited Petrus van der Velden to New Zealand, gave Christchurch his much-loved Dutch funeral (1872), and in 1964 Heathcote Helmore bequeathed perhaps our most important historical work, Gerrit Dou’s The physician (1653). In 2010 Gabrielle Tasman, a Christchurch Art Gallery Foundation board member, was a major contributor to The Leuvehaven, Rotterdam (1867), an early van der Velden painting purchased in the memory of her late husband, immigrant businessman Adriaan. This work was completely unknown when former gallery director T.L.R. Wilson compiled a comprehensive catalogue of the artist’s work; now it greatly enhances our knowledge of the world from which this artist came and provides an extraordinary contrast to the romanticism of his locally better-known paintings made in Otira.

Our Dutch works are a tangible example of how a collection builds on its strengths and over time is enabled to show more of the back story of a given artist and more of our shared history. I loved standing in a particular spot in Brought to Light, our upstairs collections exhibition from 2009, after we’d bought The Leuvehaven with matched funding from the recently established Challenge Grant, and seeing the progression of van der Velden’s interests in three key works, all visible at the same time.

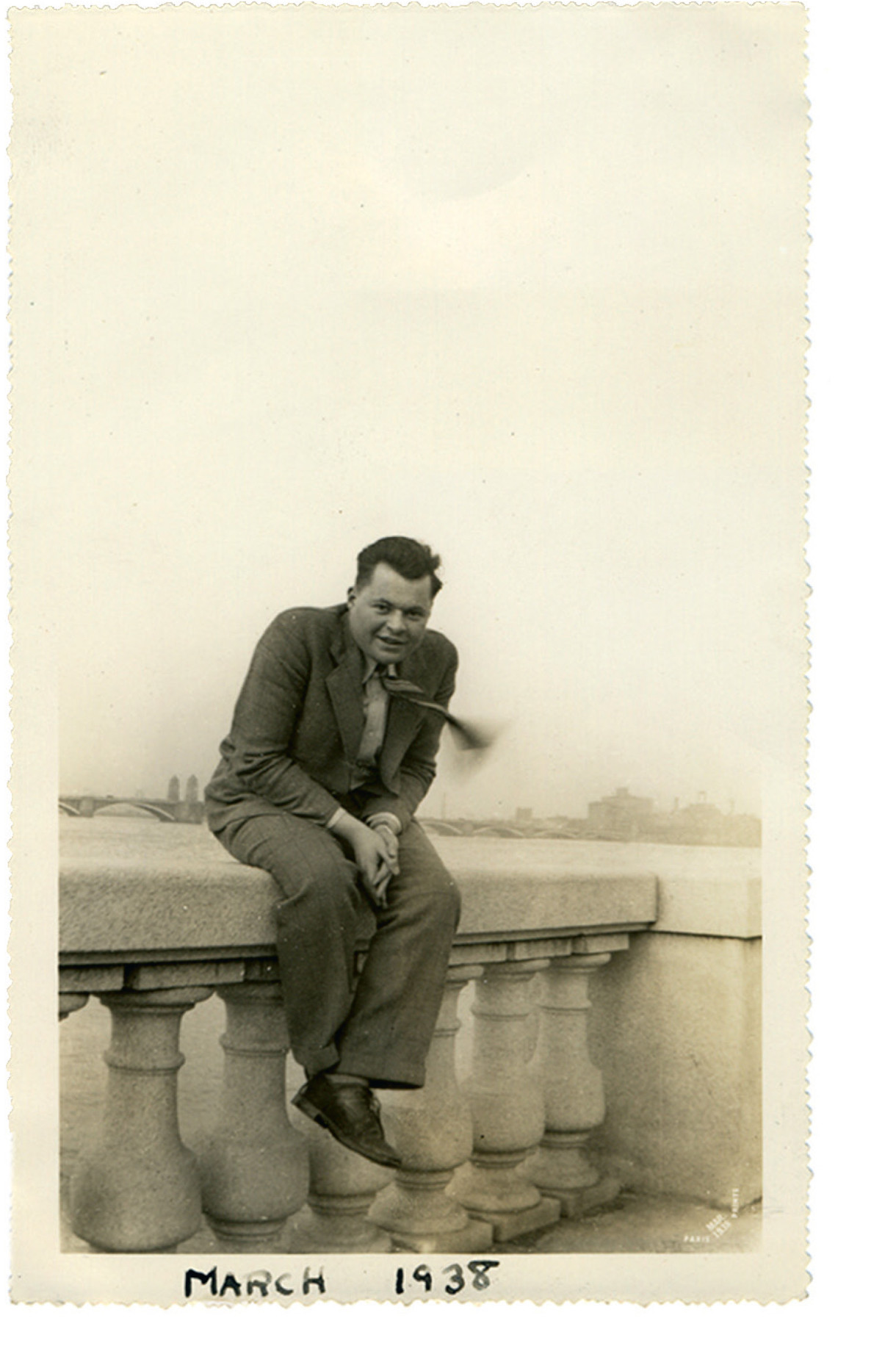

In 1938 the family of expatriate Raymond McIntyre donated paintings from England, the same year that McDougall also gave Ernest Gillick’s Ex tenebris lux (1937). Apart from occasional gifts, however, the collection remained fairly static until 1949 when the City Council established a collecting fund and began to allow for the more pro-active collecting associated with lively art galleries fulfilling a public remit world-wide. 3

In the years following World War II, collecting activity focussed primarily on historical works by European artists, with notable exceptions including Rita Angus’s Cass (c.1936), acquired in 1955; and Colin McCahon’s Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is (1958–59), presented in 1962. 4 And thinking of the 1950s, each time I look at an image or the online label for our painting by L.S. Lowry, Factory at Widnes (1957) and note that it was acquired for Christchurch the year after it was painted, I wonder at how it would be if our budget stretched to purchasing equivalent works by contemporary British artists now?

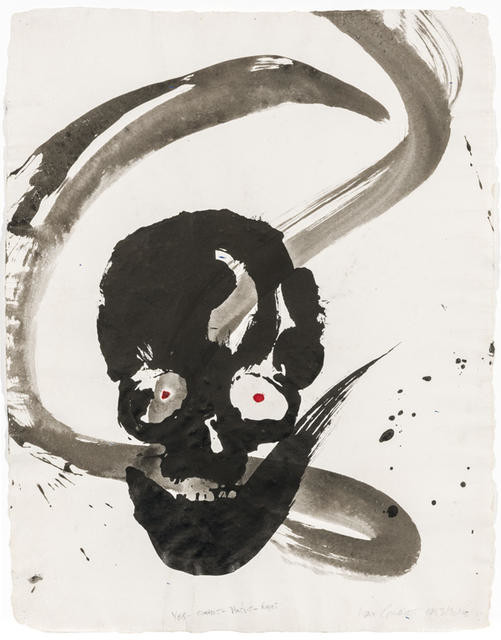

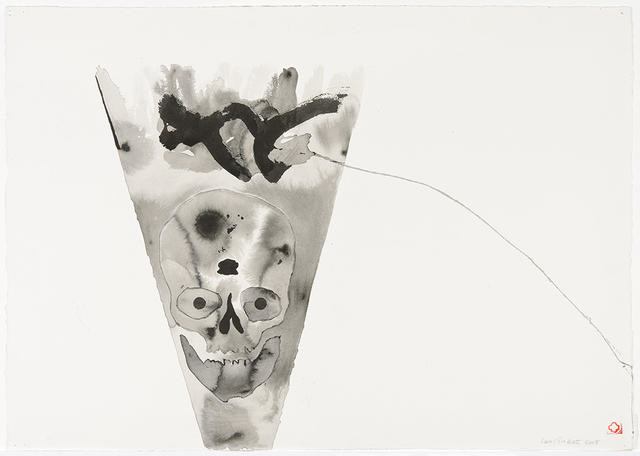

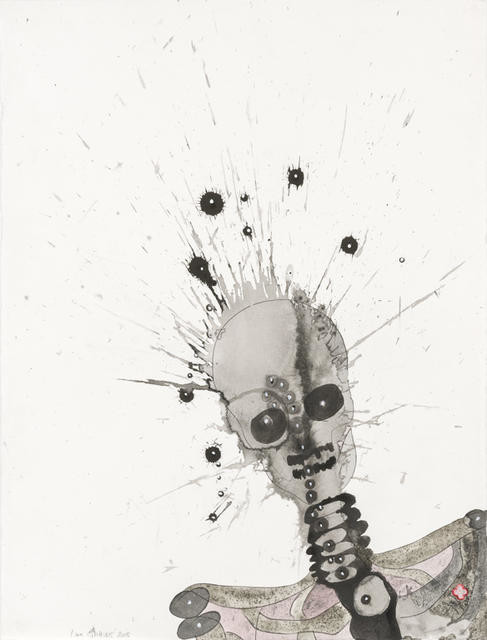

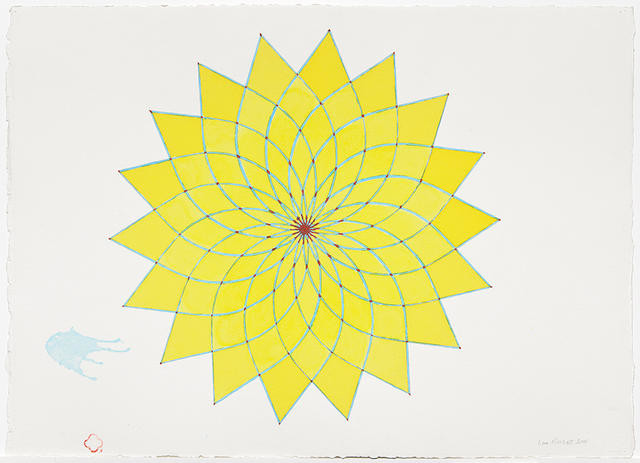

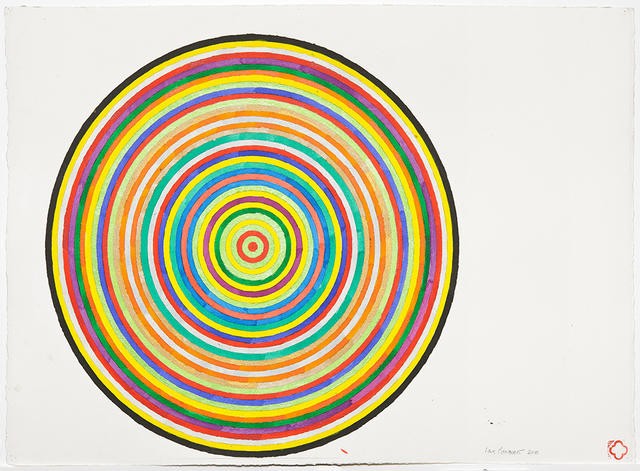

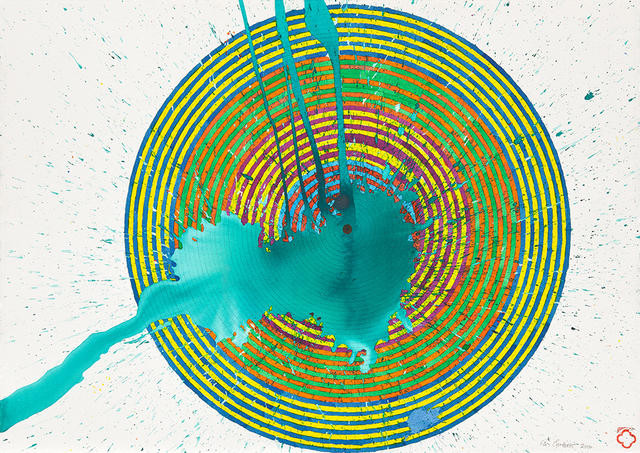

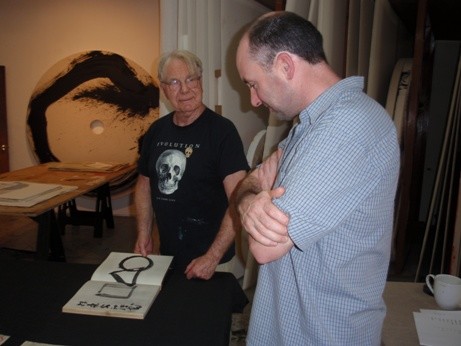

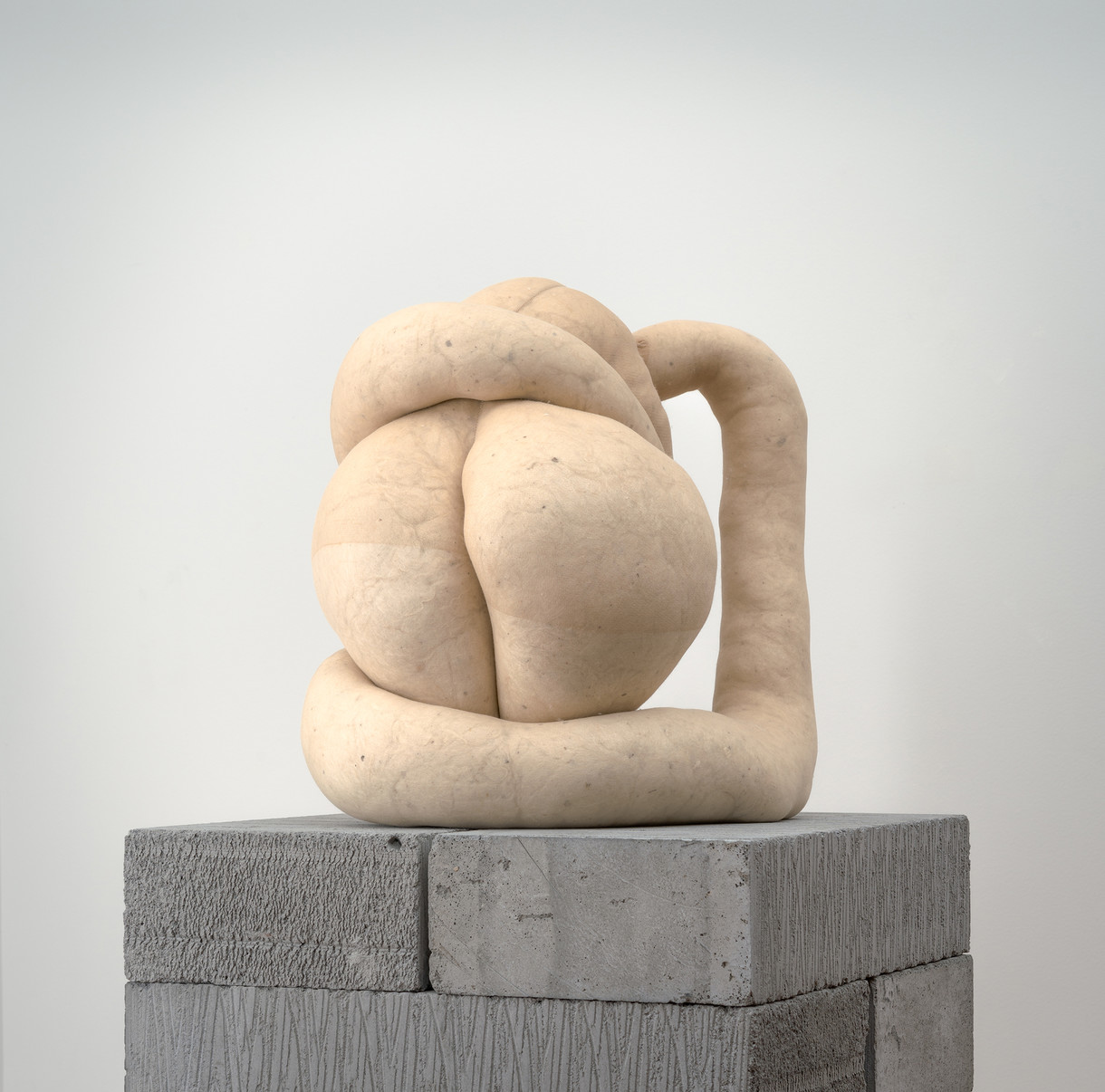

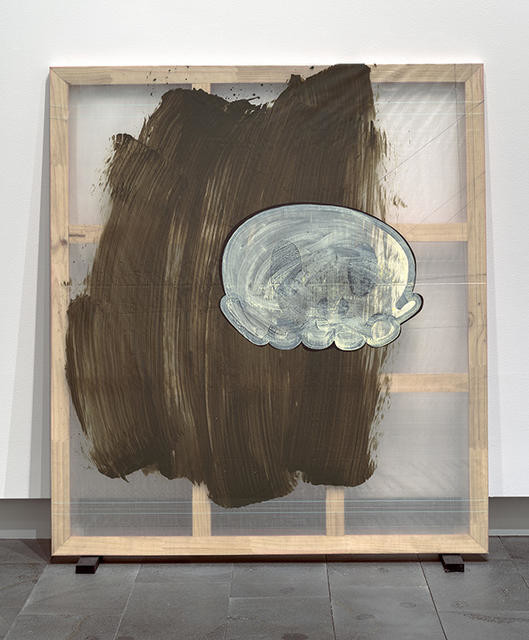

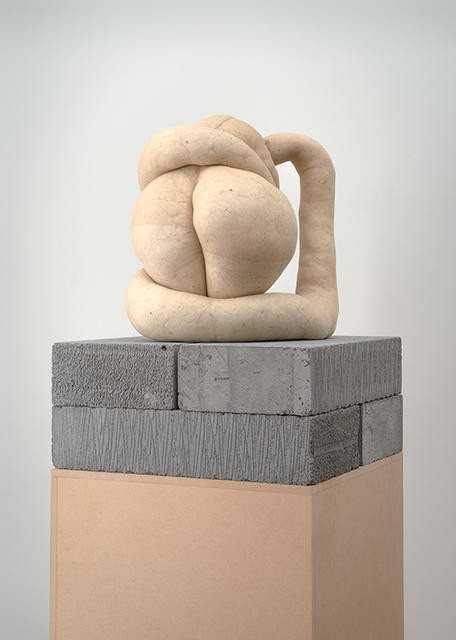

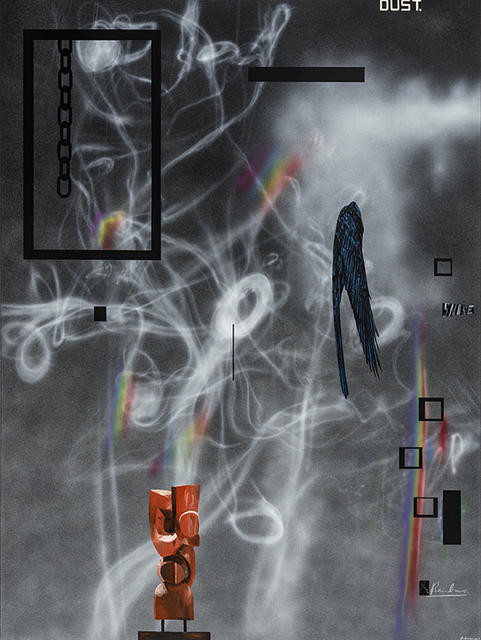

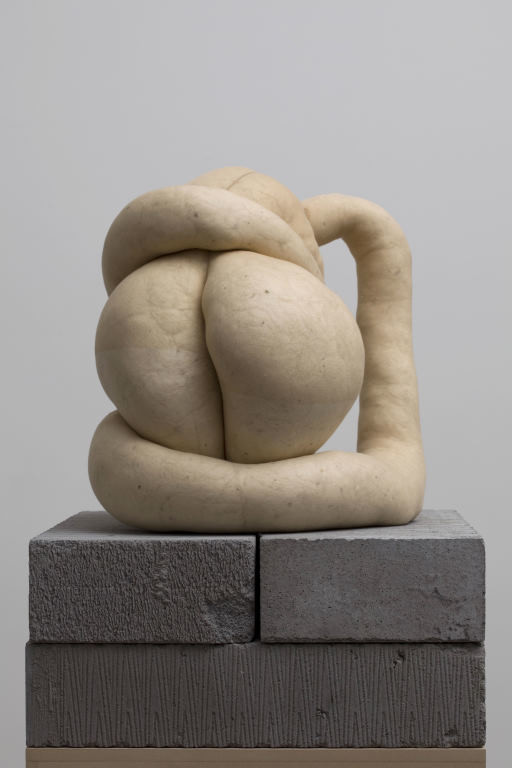

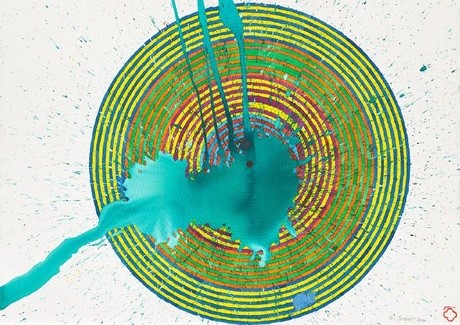

The 1970s was a decade of artists’ gifts, with works for the collection donated by several including Ria Bancroft, Don Peebles, Barry Cleavin and Bill Sutton.5 Artists continue to be generous to us, with recent gifts of work by Philip Trusttum, Max Gimblett, Shane Cotton, and Sarah Lucas being added to the collection in recent years. And since the Gallery has been closed following the Canterbury earthquakes, we’ve continued collecting quietly, only able to imagine visitor responses and possible contexts for these works, as yet unseen in Christchurch. 6 Christchurch’s collection now numbers 6,500 works of art: paintings, sculptures, and works on paper (paintings, prints, drawings and photographs) as well as smaller collections of ceramics, glass and works in new and mixed-media. This may sound a lot, but it’s important to recognise that ours remains the smallest collection of the four main centres in New Zealand, both numerically and in terms of overall value. It has some wonderful gems, which engender considerable civic pride and which we celebrate in many ways, while being realistic about its overall value relative to other places.

On average, prior to closing, this gallery showed around twelve percent of its collections, a slightly better than average percentage. For while some contemporary works such as Bill Culbert’s Pacific Flotsam (2007), and et al.’s That’s obvious! That’s right! That’s true! (2009), may take up a whole room, many are diminutive and fragile. A large proportion of Christchurch’s collection (more than sixty percent) is works on paper. While curators devise rotational displays within the long-term collections, and while appointments may be made to see these when we re-open, they cannot be shown for extended periods because of the risk of damage from exposure to light.

Gerrit Dou The physician 1653. Oil on copper. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Heathcote Helmore Bequest 1965

COLLECTING—PRIVATE AND PUBLIC

Of course, individuals collect—whether family letters or photographs, books, wine, Matchbox toys, or art. Occasionally collections become unwieldy and eccentric, gaining a sort of fame or notability in their neighbourhood. But we can’t all collect everything; it’s not practical, nor do most of us have the available time, connections or space.

A city’s institutions must take over, preserving memories on behalf of the community, revealing the multiple strands of our pasts and present. Collections matter because works of art hold stories. Our storerooms—and soon our exhibition spaces—are full of stories: about places, people, artists, ideas, and about us. These stories overlap and interlock. They give us perspectives on the times and places we’ve lived and explored—from the suburbs of Christchurch, to Canterbury’s high country, to other parts of New Zealand and beyond to the Pacific, Asia, and the rest of the world.

Christchurch Art Gallery is this city’s treasury of visual culture; a pātaka of our history; a rich armoury of images, memories and ideas. Without a collection, single works come and go. The lines connecting them to each other and to us are seldom drawn. The Gallery’s collection is part of us, but with more continuity than any one of us and it gets more interesting over time.

The Gallery doesn’t stand alone in its collecting for Christchurch. It is part of a tapestry of institutions (including museums and libraries) which collect examples of what we broadly term culture. Along with spaces with a contemporary remit, such as the Physics Room and the shortly re-opening Centre for Contemporary Art in Christchurch, this Gallery shows and promotes the understanding of current art and supports the creativity of artists. However, unlike the other contemporary spaces, and always within a limited budget, we collect.

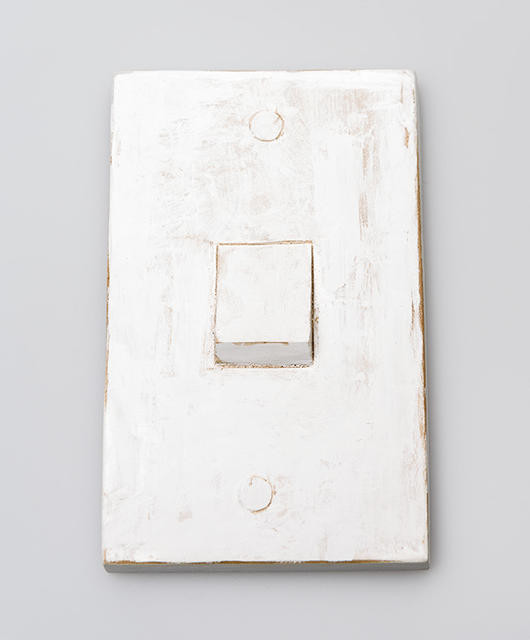

Collecting is a continuous process. You can’t turn it on and off like a light bulb. It’s proactive and it takes knowledge, commitment to developing relationships with artists, their dealers and auction houses, as well as the experience and judgement we develop on the job. We cannot rely on gifts of works of art alone. For the generosity of individuals cannot be expected to stand in for the duty of governments and locally-elected councils to protect an independent and democratic stake in arts and culture.

This Gallery is not restricted to collecting on a domestic scale; and we don’t collect only what’s easy to live with. We collect works which are relevant and which enhance our collections and our ability to understand them. We recognise Ngāi Tūāhuriri as mana whenua, and we’re mindful of the increasing cultural diversity of Christchurch and New Zealand in developing our collection. We are building a collection of its time, worth seeing now and in the future.

Let’s not forget the important fact that people come here to see our collections. In 2010–11, the financial year in which we closed, when we were confidently predicting more than 700,000 visitors to Christchurch Art Gallery, a number more than twice the population of this city, we showed the hugely successful Ron Mueck exhibition 7, neatly sandwiched between the September 2010 and February 2011 earthquakes. Throughout the time of this exhibition, forty-seven percent of all gallery visitors saw Ron Mueck, with fifty-three percent choosing to visit the collections.

The more important our collections, the more we can form genuinely reciprocal relationships with other art galleries and exchange loans for specific exhibitions. Imagine Te Papa’s 2008–09 exhibition Rita Angus: Life & Vision without our Cass (c.1936). And imagine how much stronger our bid to be part of this tour became when Christchurch lent Cass and eight other works by Angus for the exhibition and national tour.

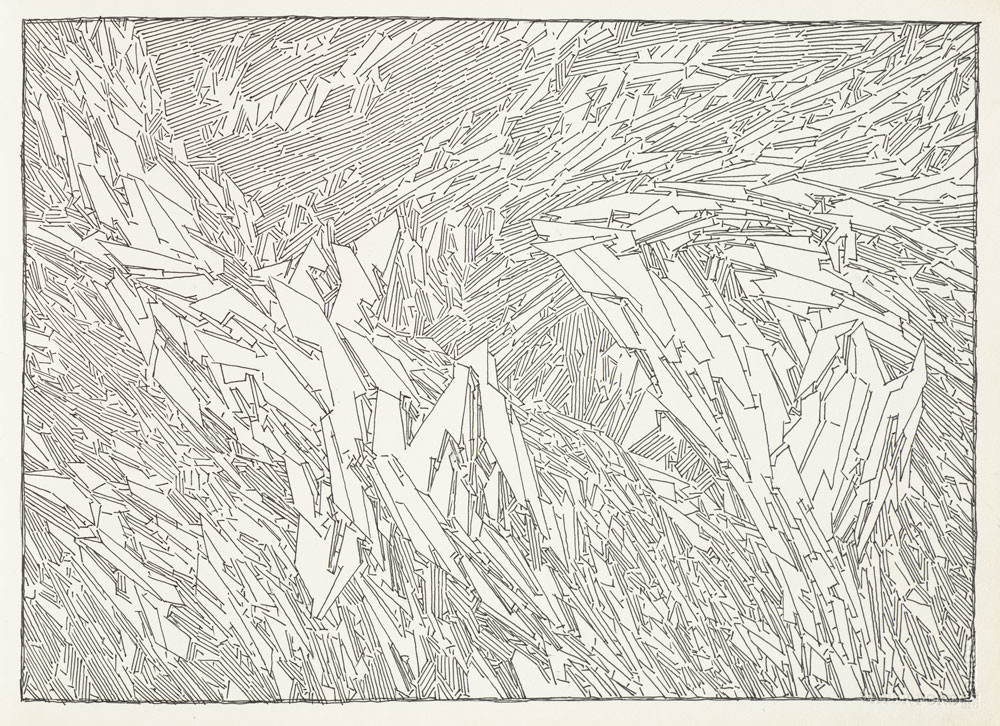

Barry Cleavin, The hungry sheep look up– the final solution (2) 1996. Etching. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū 1999. Reproduced courtesy of Barry Cleavin

ROLE OF THE GALLERY IN A NEW CITY

Because of this city’s collections and the way we interpret, present and expand on them with shorter-term and borrowed exhibitions, we can confidently describe our Gallery as the cornerstone of art in Christchurch. We see ourselves as the pulse of a new city, the centre of which needs continuing intensive care. The reopening of Christchurch’s Art Gallery is crucial to this city’s recovery.

Over more than four long years, a productive core team has remained, now with increasingly tangible plans for re-opening keeping us buoyant. Our focus will be people, people, people. To adapt the great German artist Joseph Beuys’s axiomatic statement, ‘Everyone is an artist’; I want Christchurch Art Gallery to demonstrate how much ‘Art is for everyone’.

During our closure, we’ve organised more than ninety Outer Spaces projects and temporary exhibitions in different, sometimes make-shift, city locations and we’ve maintained our relationships with artists (for their creativity inspires ours) and our audiences as well as we could. Our gallery without walls has led to recognition for our Gallery’s staff here and internationally. Speaking for myself, however, more than anything during this time, I’ve missed seeing people engaging with our collections and programmes every day.

When Christchurch Art Gallery re-opens, our visitors will enjoy the presence of old favourites back on view and be excited by a range of works they’d forgotten. We hope they will also be moved and surprised by what has been acquired since we closed for renovations. Many will experience great delight in spaces that have been absent so long. Sometimes we take comfort in art, sometimes it tosses a conundrum our way and we’re challenged.

Auckland collector, Rob Gardiner, one of New Zealand’s few really committed art philanthropists, who has enriched Auckland Art Gallery’s collection immensely with the extended loan of his Chartwell Trust collection, sometimes describes art as a ‘gymnasium for the mind’. And, just like getting fit, sometimes it takes time and energy to engage with art. Furthermore, we simply don’t have to like everything the Gallery buys or shows; our visitors are completely free to leave a bewildering work behind and come back to it another time (or not).

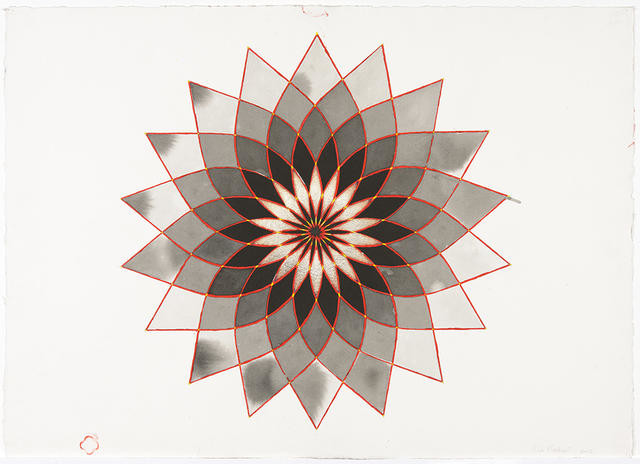

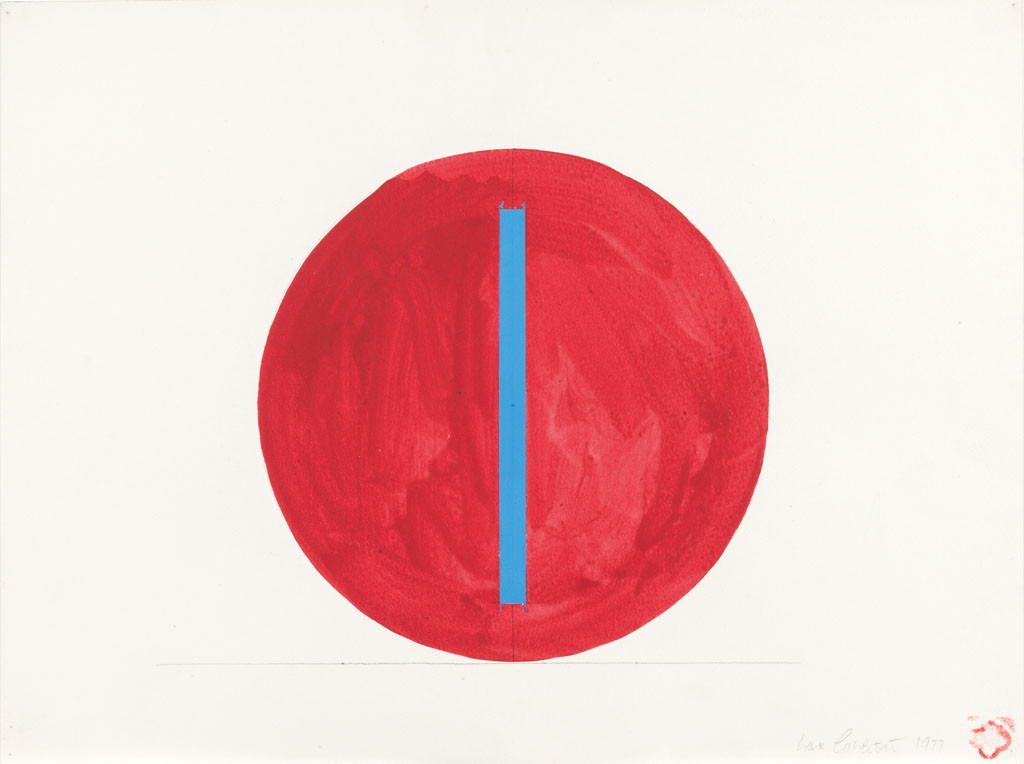

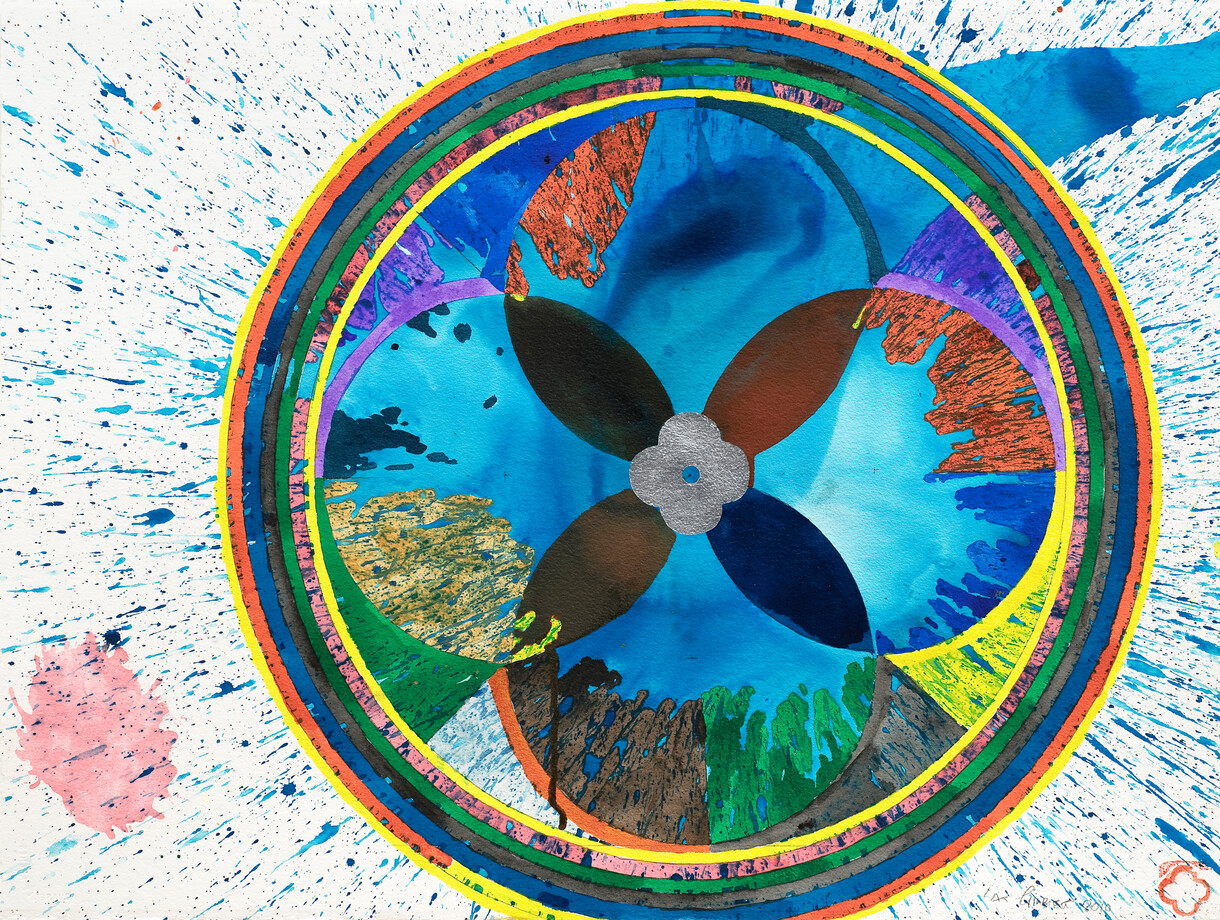

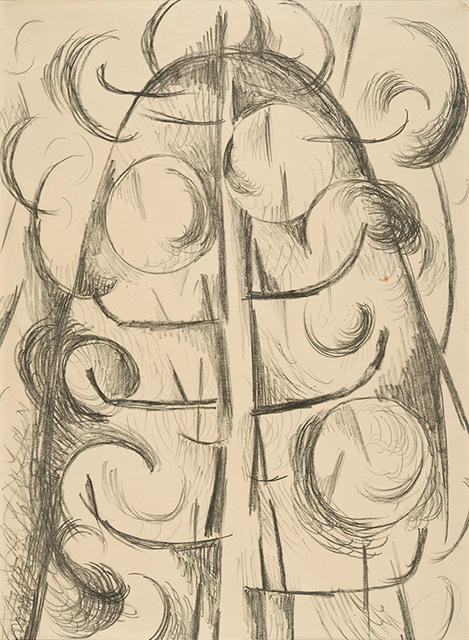

Max Gimblett, Center Turning 1977. Pencil and acrylic polymer on watercolour paper. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū 1999, the Max Gimblett and Barbara Kirshenblatt–Gimblett Gift

COLLECTIONS SUPPORT

This Gallery was among the top three city facilities people wanted restored to them when The Press polled Christchurch residents in May 2012. 8 It will be the first city-operated cultural building in the city’s centre to be brought back into full use following the disruptions which changed our city forever. Hallelujah.

When we re-open, the Gallery will once more be a social, educational and, I think, a spiritually uplifting place to learn and enjoy. We will build a community around the Gallery and its collections—a community which wants to think, get together, discuss art, and see collections strengthened. We will mount a range of exhibitions, current in their intellectual basis and occasionally contentious. We want to be thought leaders and acknowledge that—like university academics—one of the key roles artists (and by extension we) play is to be critic and conscience of society.

We recognise that the city in which we re-open will be different from the Christchurch in which we were closed. It will be more diverse, thriving in some areas, eerily empty in others—especially in parts of its centre. It’s a place distorted by coming to terms with its need for transformation, at the same time as struggling with debt. For now, Christchurch is unusually focussed on the necessities of life, rather than what some of our decision-makers, elected and employed, judge as ‘nice to haves’. As we know, it’s rare for shorter-term gains not to dominate politicians’ collective thinking within their inevitably limited tenures.

But let's remember that, whether we’re well-off or relatively poor, each of us is acculturated within whānau and wider families and within cities, their social settings and institutions. A range of art spaces is crucial for the wellbeing and the broader economy of a rounded community. As studies elsewhere show, there is nothing ‘nice to have’ about art, nothing tangential, nothing ‘soft’. 9 The arts are central to our economy, our public life and our cultural health and wellbeing. People will want to live here if art and culture is supported openly and integrated strongly into this city’s recovery. Visitors will stay longer with a range of freely accessible, reliably good quality things to do and see.

There’s been talk within the arts sector and during the city’s 2015–24 long term planning process of how an updated city arts strategy is needed. Equally crucial for the arts, however, is the need for us to be seen as a pillar of the city’s visitor strategy, an essential pivot of its wellbeing. Art galleries, museums and contemporary art spaces must research and articulate our value to the local economy and to the community’s maturity and wellbeing. Imagine London, Paris, New York or any Australian state capital without their galleries and museums. Consider the transformation of Brisbane that began in the 1970s with the development of the South Bank precinct, now with two sizeable state-funded art galleries under one umbrella.

Everyone who travels knows how important public art galleries and museums are in forming one’s view of another place, in grappling with its identity, in summarising what’s special about it. Collections reflect and enhance a city’s reputation. Christchurch’s art collections provide a sample of cultural DNA you can find nowhere else on the planet, as well as numerous examples of generosity—individual and collective.

Now is the time for the arts and the Gallery to ensure our funding is firmly integrated into the city’s plan, so that we can enhance longer-term cultural wellbeing. Imagine if Christchurch became an essential destination for cultural tourists as well as the gateway to the South Island’s great outdoors. Let’s build this into our recovery plans. Let’s invest dollars to ensure people stay extra nights in Christchurch to experience the rich diversity of its arts. The alternative is that artists become increasingly detached from the city’s concerns, and that visitors pass through instead of staying and talking about Christchurch in a positive and compelling way.

We cannot politely retreat or stagnate in adversity. We must collect and show art being made now, and grasp opportunities to enhance the historical fabric of our collection where we can. I believe, increasingly throughout the world, but perhaps especially in this part of the world, contemporary art has moved from the margins to the mainstream. Cities are judged by their alertness and responsiveness to art’s questions and provocations.

I am disappointed at the recent effective halving of public funding for building core collections and some of the views expressed publicly to justify this. Clearly there is a broadly informative role we need to play and play well when we re-open. Christchurch’s collections need public as well as private support. 10

In the wake of this news, Christchurch Art Gallery Foundation’s TOGETHER endowment campaign is even more necessary now than when it was established—and will in the future be able to provide a buffer for us in this very situation. The Friends of Christchurch Art Gallery have helped to enhance the collection over the years. The Foundation’s new endowment fund provides a framework for more individuals and small businesses to make a tangible long-term impact on our collections. If you would like to be involved, our Foundation insert in this edition has more information. Help us continue with our core task of collecting, and help us mark this extraordinary time with the presence of important art.

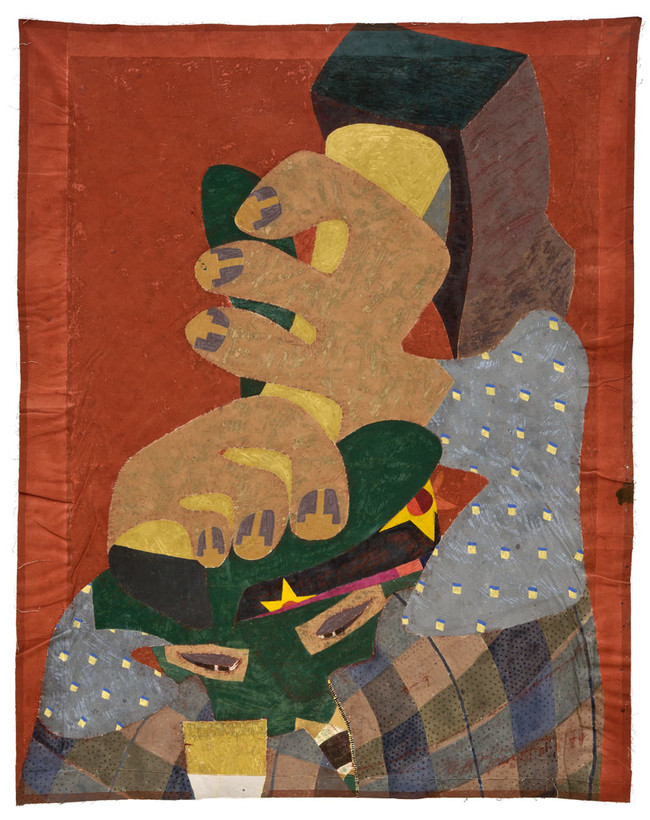

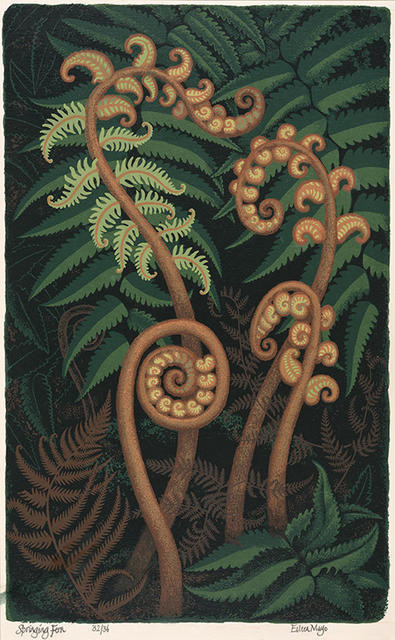

Philip Trusttum Heavy going 1989–2000. Acrylic on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, presented by the artist 2009

![Untitled [Quentin (Kin) Woollaston Shearing]](/media/cache/77/39/7739de21a36f594ddb27e21bdc361bcb.jpg)