The fault is ours: Joseph Becker on Lebbeus Woods

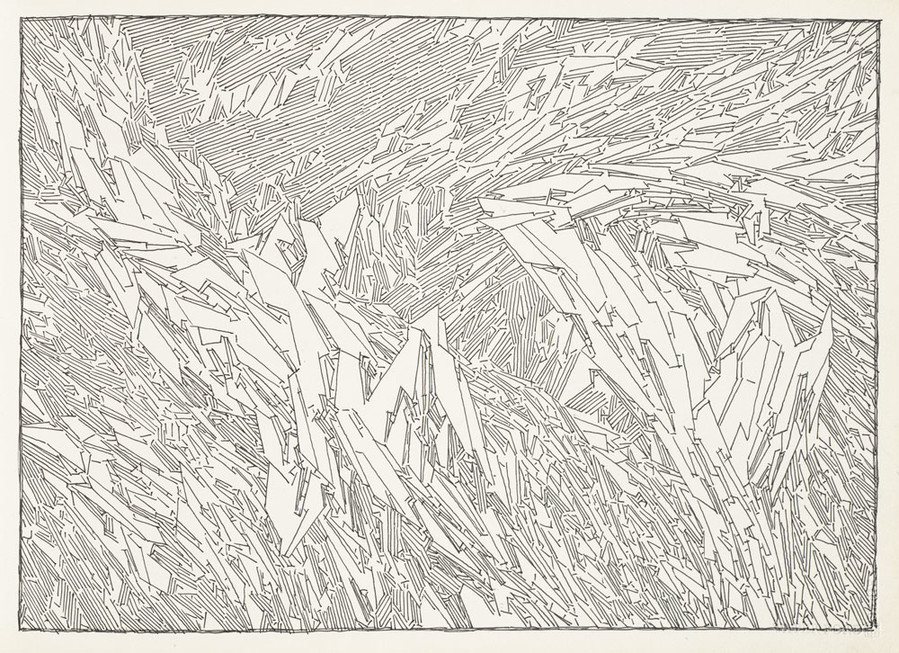

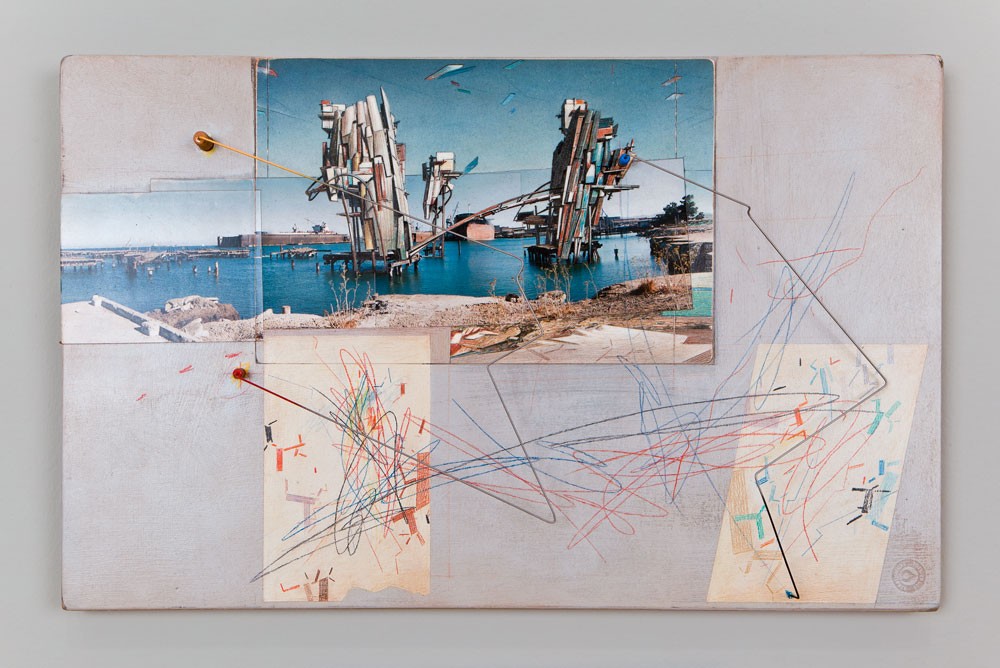

Lebbeus Woods Sketchbook (30 July 1995, NYC - 23 May 1998, NYC) 1995. Ink on paper. Collection SFMOMA, Accessions Committee Fund purchase. © Estate of Lebbeus Woods

There was a packed auditorium at CPIT in Christchurch this August when visiting San Francisco Museum of Modern Art curator Joseph Becker delivered a lecture on architect Lebbeus Woods. And it wasn't hard to guess why. In addition to many other achievements, Woods is renowned for his highly speculative project, Inhabiting the Quake. Senior curator Justin Paton spoke to Becker about Lebbeus Woods, and what Christchurch might learn from him.

JUSTIN PATON: You came to Christchurch to talk about the architect Lebbeus Woods, who is not an architect in the sense most people are used to. Could you say a little about Woods and the context he emerged from?

JOSEPH BECKER: Absolutely. To put Woods in proper context it's important to paint a little bit of the picture of his upbringing. He was born in 1940 and grew up as the son of an army engineer in the thick of the Second World War and during the development and evolution of the atomic bomb. His father, Colonel Lebbeus Woods, was responsible for a lot of the infrastructural developments related to the Manhattan Project, so Woods junior, Lebbeus, was around all of these large engineering projects – aeronautics, wind tunnels and fighter jets – and I think that established a design and engineering sensibility in him at a very young age. His father ultimately died of radiation poisoning from the Bikini Atoll atomic tests, and Lebbeus Woods was also affected by a very raw understanding that, through engineering, there could be both the creation of something and destruction and chaos. This probably also led him towards a certain fundamental distrust of governments and institutions – the idea of some heavy hand that was not his. Perhaps with this in mind he studied engineering at Purdue and architecture at Urbana-Champaign where he was exposed to the idea of cybernetics and the science of thinking. He then entered into architectural practice, working for Eero Saarinen and Associates after Saarinen's untimely death and the firm's transfer to Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo, and was involved in key projects focusing on architecture's capacity to craft an experiential space for its inhabitants. And all the while he's developing his own voice, his own architectural language, working as a freelance illustrator and architectural renderer, honing his skills and his technical capabilities in clearly rendering an architectural idea.

JP: At that point, though, he was perhaps not so different from many other young practicing architects. What was it that started to set Woods apart from architects as we normally encounter them?

JB: The major difference is that Woods was seemingly never fully interested in actually building his buildings. He was more interested in the idea of architecture for its own sake, and by that I mean architecture that was not for clients, or money, or even for glory, but more focused on underlying philosophical concerns about what architecture is and what it has the potential to become. By separating himself from some of the practical requirements of professional architecture, such as building permits, or the potential design derision of corporate clients, or even from dealing with forces like gravity, he was able to focus on the question of what it means to exist in a world that we can create. What does it mean to exist in an architecture that we can be responsible for? What can we do with that responsibility? This was also at a time, in the late 1970s and the 1980s, when the idea of practicing a more conceptual architecture, and not 'selling out' to the capitalist system of building, became a badge of honour. There was a very interesting conversation flowing through academic circuits and publications, with people pushing against the common understanding of what architecture is. And Woods was at the centre of that.

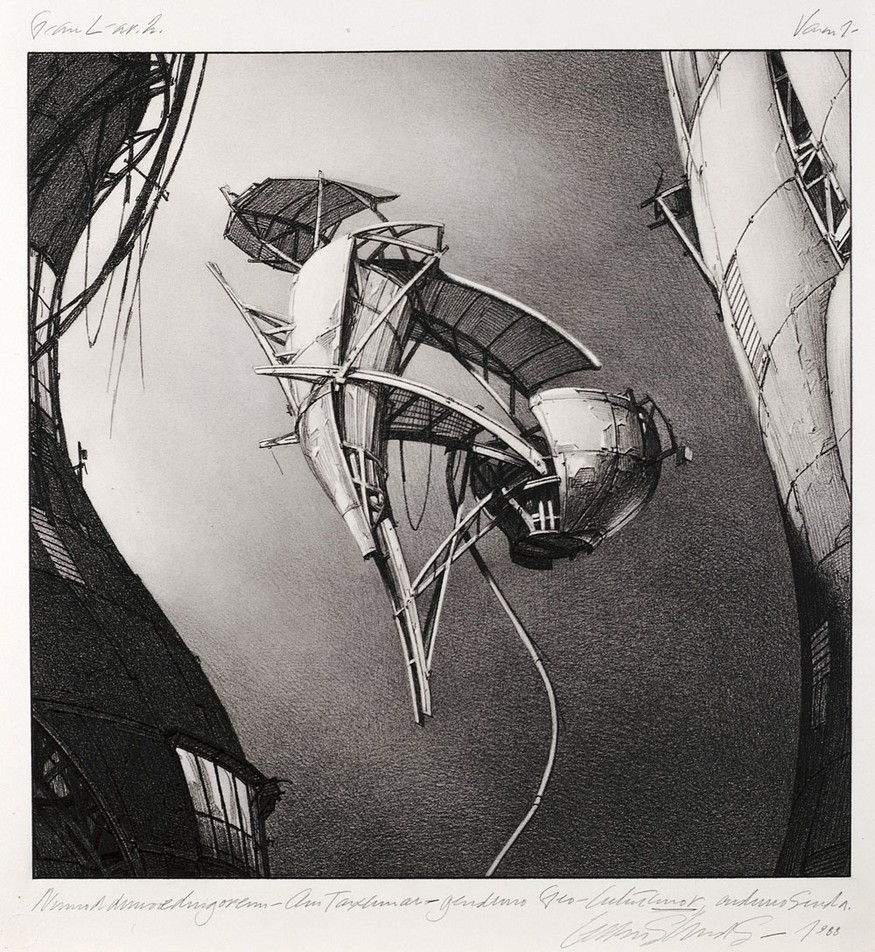

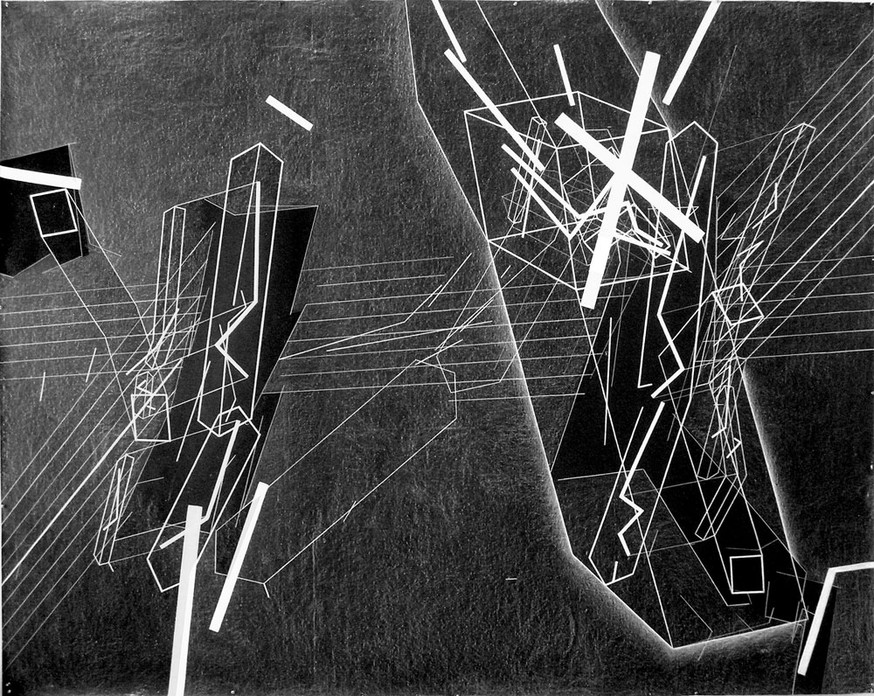

Lebbeus Woods Photon Kite from the series Centricity 1988. Graphite on paper. Collection SFMOMA, purchase through a gift of the Members of the Architecture + Design Forum, SFMOMA

JP: What triggered this push towards conceptual architecture? Was it disenchantment with commercial models?

JB: It was a common feeling at that time that corporate interests were taking over. To have clarity of architectural vision in that social context was difficult, especially if you were trying to execute your ideas through actual buildings. A built version of the architectural idea would not necessarily provide the conceptual rigour that Woods wanted and which he could execute more successfully through a drawing, a model or his writing. His aim was to describe the potential of architecture, rather than creating something three-dimensional and inhabitable that we would commonly consider architecture.

JP: Ceasing to make buildings might strike some observers as a withdrawal or a retreat. With that potential criticism in mind, how did Woods make his ideas known? How did he disseminate them?

JB: It's a good question because, if you consider the idea of architecture as a career, then you know your cachet lies in realising your projects. But Woods was very adept at keeping himself relevant. He taught for many years at Cooper Union's School of Architecture, along with others, and also founded what is called the Research Institute for Experimental Architecture in the 1980s, which he saw as a new model for teaching architecture through conceptual practice. He also lectured internationally, and published his drawings and writings. He undoubtedly practiced architecture even though he never built buildings.

JP: And can you talk a little about the things he did make?

JB: He was extremely talented with the pen and the pencil, and he had such an ability to describe architectural ideas clearly that the drawings and models were capable of standing as artworks in their own right. They have this quality of labour and attention to detail that is seldom found these days in architectural practice.

JP: Is that due to the widespread use of computer-aided design?

JB: Absolutely. The pen and the pencil are very much still tools of the trade, but for sketching. The computer is such an important and functional device that it has essentially trumped the need for somebody to describe a space by hand, or illustrate the essence of a space by hand. So Woods was among the last, and perhaps the best, of a generation of architects who did this, who rendered the potential of a space by hand. There are some who have the technical skills, but the conceptual rigour of Woods's work sets him apart. He wasn't just a renderer, he was the creator and author of these ideas.

JP: When I look at the works, I think of the tradition of fantastic architecture, from Piranesi's Carceri etchings all the way through to the structures seen in science-fiction movies. Was there a fantastic dimension to what Woods was doing? Did sci-fi influence him or the other way around?

JB: This idea of fictional architecture, or even science-fictional architecture, is tricky for me. I wrestle with it in relation to Woods because a common perception of science fiction is that it's there more for amusement or escape than for deep contemplation about how the world works – that it's involved with imagining a world that is impossible. And with Woods, I'm less interested in thinking about the impossibilities than I am in thinking about the possibility of his projects. What if some of these things were realised? What effect would that have on our social perceptions? Our engagement? Even our communications?

Lebbeus Woods SHARD House, from the series San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake 1995. Graphite and pastel on paper. Collection SFMOMA, Accessions Committee Fund purchase. © Estate of Lebbeus Woods

JP: Woods had a strong connection with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, where you're assistant curator of architecture and design. Can you talk about the major project he realised there?

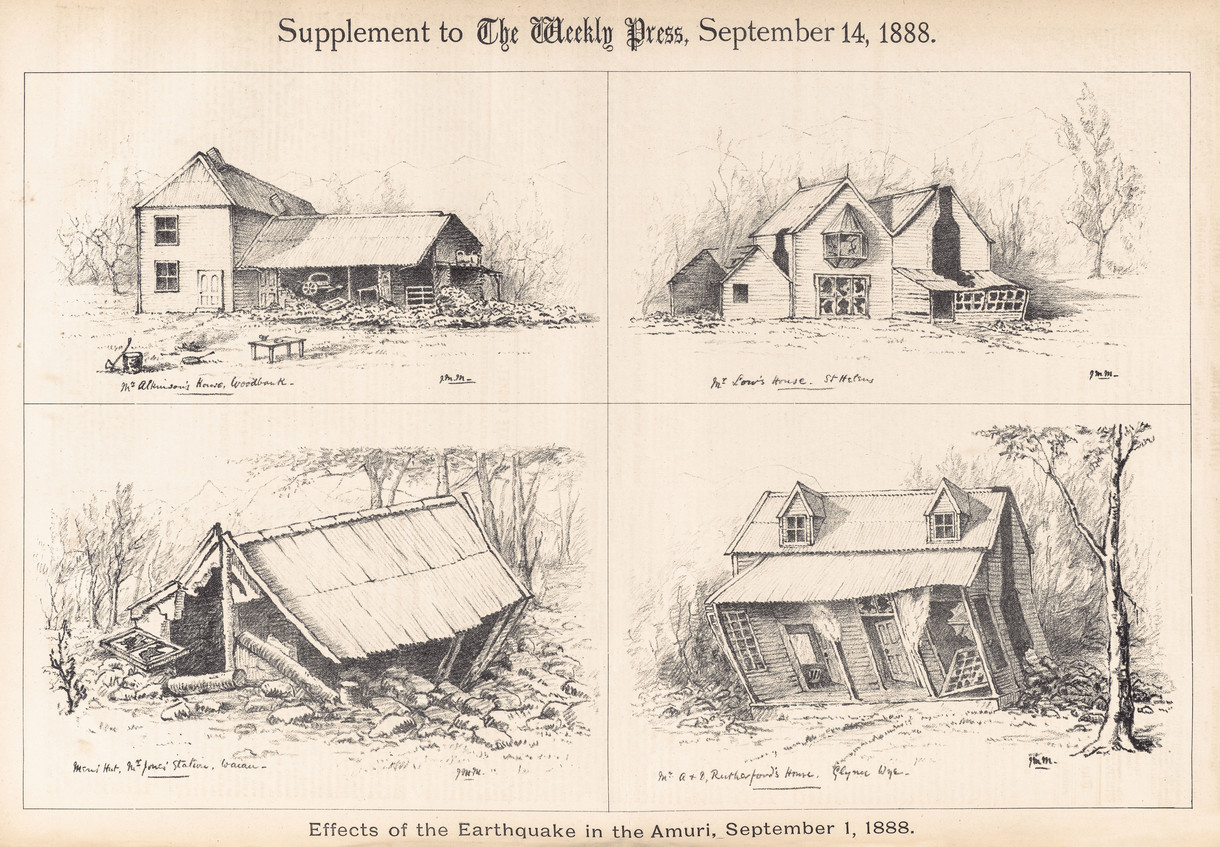

JB: Woods had a dialogue with Aaron Betsky who in the mid 1990s was the curator of architecture and design at the museum. Following the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake that shook the Bay Area and the series of earthquakes in the 1990s that included Kobe and Los Angeles, Betsky commissioned Woods to come to the Bay Area and do a project based on the idea of the earthquake. Woods responded by attempting to take the event of the earthquake and turn it into something that was not necessarily chaos and destruction but a potential creative power. He was looking at the way that we perceive natural disaster as a negative, almost like an affront to humanity and to the evolution of civilisation. And he was challenging that idea and saying that we are looking at these seismic events in a backwards way. What if, instead of being victimised by the earthquake, we used architecture to embrace it, allowing variations within our architectural programmes that are generated by seismic activity? Woods created these amazing panels describing different types of houses or spaces of inhabitation that were all engaging with different aspects of seismic activity.

JP: Thinking of Christchurch and the many discussions here about building, I'm interested to know how the project, called Inhabiting the Quake, was received. What uses did local architects or viewers have for it? Did it have an appreciable effect on the wider conversation?

JB: I think with Woods's proposals, his goal is to plant a seed for other architects, engineers, planners and urban designers to start thinking more broadly and 'outside the box' about the way that we construct buildings, the way we inhabit buildings, even the way we take buildings apart. Because his proposals are very radical we can't really hope to see them realised by other architects yet. But what we can hope for is incremental change. This might begin with a shift of focus from the aesthetic of architecture to more concentration on things like base isolation and allowing certain kinds of flexibilities to begin to inform a building's design.

JP: That word 'inhabit' in Woods's title is fascinating. It seems to suggest that words like 'post-quake' are misnomers – that we are always living in the quake, and that we should never consider that it is behind us. What's your understanding of the phrase?

JB: Yes, it's multilayered. It's the idea of 'inhabiting' not only in space but in time, and it's not only a physical act but a mental one too. He's suggesting that we embrace or acknowledge the fact that we are responsible for the effects of the earthquake. He's calling attention to the fact that the problem isn't that the earthquake, operating independently, destroys the buildings, it's that the buildings have not been built for the earthquake. So he's encouraging us to inhabit the mindset of nature, inhabit the moment of the earthquake and, instead of being passive, to be an active participant in the process.

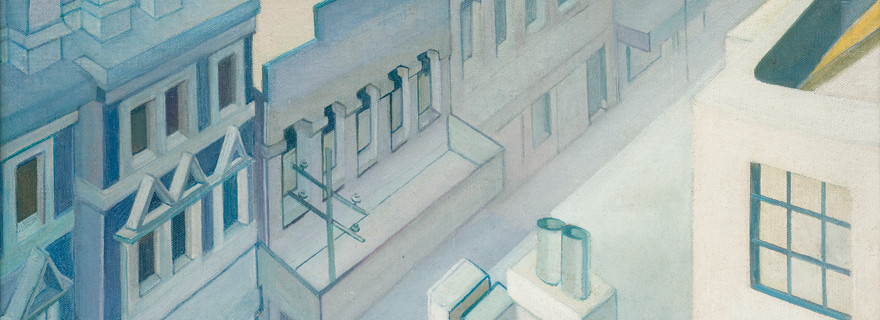

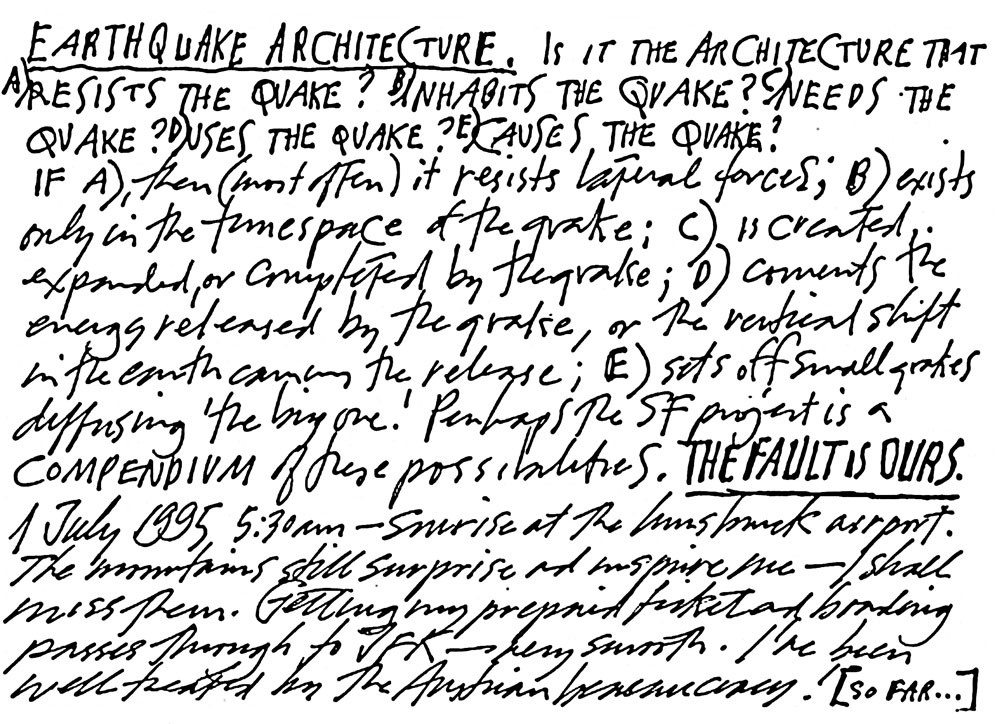

Lebbeus Woods Sketch 1995. © Estate of Lebbeus Woods

JP: That reminds me of another work by Woods that you presented in your Christchurch lecture [above], which I think many in the audience took away as a lasting mental image. It was a postcard, is that right?

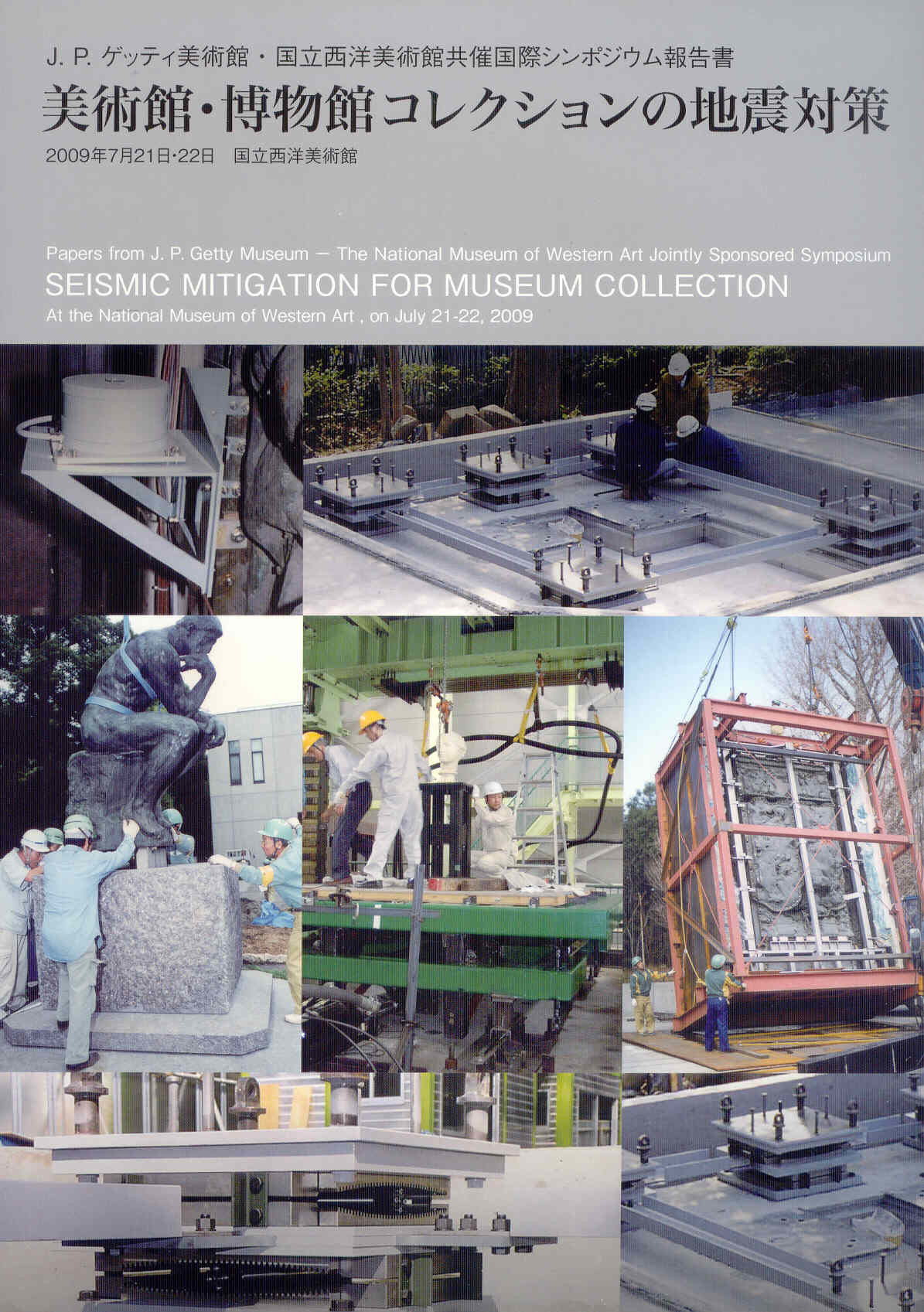

JB: It's a note from his initial workings for the Inhabiting the Quake project. Woods is looking at the ways seismic actions present themselves and the ways we deal with those actions. He's looking at whether we should resist the earthquake with our architecture, or whether we should try and use or harness it. Or whether we embrace it, and even imagine an architecture that causes minor seismic activity so as to prevent major catastrophic quakes. He's generating these little notes that present a series of possible responses. And the key linguistic tool he uses here is the word 'fault', which is of course the fault line but also the idea of responsibility. So in the image I showed in Christchurch [see overleaf] he says, 'The fault is ours,' which is incredibly poetic. It inverts our traditional understanding of responsibility.

JP: It's terrific – a catchphrase for Christchurch to live by. With Woods's images in your mind's eye, how did the current Christchurch cityscape strike you? You arrived not long after some large tracts of the 'red zone' had been reopened to the public.

JB: It was hugely fascinating to see not only the effect on architecture but also on the physical landscape. As I walked and drove through, two different paths of thought began to intersect. One concerned the incredible dynamism within that landscape, where the ground has dramatically shifted and kind of laid its evidence bare. And then also there was the undeniable feeling of vacancy and emptiness in the city, which has been cleared out not only due to seismic activity but also, to some extent, due to political activity. It's a landscape of orange cones and surveyors and demo crews and within all of this change there is such a wonderful underlying feeling of optimism and potential regarding the built space, the open space, and the city as a whole.

Lebbeus Woods Conflict Space 4 2006. Crayon and acrylic on linen. Collection SFMOMA, purchase through a gift of anonymous donors and the Accessions Committee Fund. © Estate of Lebbeus Woods

JP: Visitors to the city sometimes confess to feeling guilty for finding it so interesting to look at. Is there a danger of aestheticising disaster? What do you think Woods's position on this question would be?

JB: I think Woods would say there is really no danger in looking at the beautiful aspects of chaos. Out of this kind of destruction can come a kind of creation, a realisation, an inevitable shift in strategy or in perception. I think that, in order for that shift to occur, there needs to be an event. And seeing things distorted or twisted and laid bare can suggest alternative architectural approaches, even if those alternatives are not yet functional. You mentioned Piranesi's Carceri, his views of prisons, and it resonated a bit. They are very dark scenes in which these interweaving pathways are almost towering over you and burying you. But at the same time there is something so compelling about those images that describe a fantastically complex space. Similarly, in the architectural environment that we experience, there is something so captivating about looking at something that is both so huge and such a feat of creative energy, and simultaneously at the brink of coming completely apart.

JP: It has been like that in Christchurch, where we have been constantly exposed, through the sight of demolitions in process, to all this new knowledge about what buildings are made of – all the sinews and structures that are usually hidden inside or within. It would be nice to think that, despite the stress and trauma of demolition, some understanding comes of it.

JB: Given that there is such radical change coming to Christchurch, with so many buildings coming down and presumably new buildings coming up, there is a remarkable opportunity for people to feel directly engaged in the architecture and planning, and to start to feel like the city is again your own.

JP: The temptation is always to ask visiting authorities what they would build in the new Christchurch. But since Woods put the emphasis on unbuildable projects, I'll try a different closing question. Why does architecture need speculative and unbuildable projects to set alongside its real building projects? What might the value of the 'unbuildable' be in a city like Christchurch, currently mired in the practicalities of recovery?

JB: For understandable reasons it's all too easy to fall into the same comfortable patterns of architectural development. But the key takeaway from looking at Woods's work is that a process for any kind of radical change might take a long time, so you have to embrace the potential of subtle and small shifts in perception – in the perception of the geotechnical engineer, of the urban planner, the designer, the architect. People can come in and propose potentially great things like mixed-use densities and pedestrian-centric urban spaces, but in addition I think it benefits everybody involved to stand back and take a serious look and think again about the potential effects of living in an urban environment. Is the architecture challenging those effects? Pushing them? Stimulating them? And in my understanding of Woods, we need that thinking to take place, alongside the work of building, if we're going to move forward in a progressive way.

Joseph Becker is assistant curator of architecture and design at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. He spoke with Justin Paton in October 2013 following a speaking tour of New Zealand in August organised by the Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi, Victoria University of Wellington, and funded by the New Zealand Institute of Architects.