Here and Gone

In the last issue of Bulletin, senior curator Justin Paton wrote about the way the Christchurch earthquakes 'gazumped' the exhibitions on display at the Gallery – overshadowing them and shifting their meanings. In this issue, with the Gallery still closed to the public, he considers the place of art in the wider post-quake city – and discovers a monument in an unlikely place.

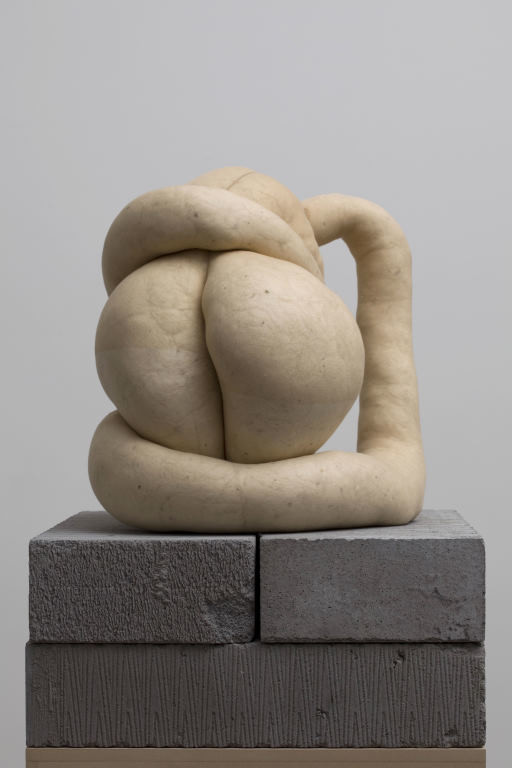

It was the best public sculpture Christchurch never knew it had. Kids peered out the car window to see it. Adults told stories about how long it had been there. Commuters measured their journeys by it. Quite a few locals simply hated it. But even if you were indifferent to its charms, it was impossible not to wonder how it got there – and whether it would ever get out.

I am talking about the big black boat that sat on the corner of Ferry Road and Ensors Road in the suburb of Woolston. It had been up on blocks there, with its paintwork roasting in the glare, for as long as most people can remember; I came to Christchurch as a kid in the late 1970s and can't recall it ever not being there. A big tub of a thing, eighteen metres long and built from ferrocement (a favoured material for amateur boatbuilders), the boat would have made a sizeable object in anyone's back yard. It looked even bigger on Ferry Road because it was parked in such a small and improbable space – backed right in behind a long corrugated iron fence, just metres from the swoosh of traffic. My earliest views of it would have been on the way back from weekend trips to the beach at Sumner, sitting with my sisters on the scalding back-seat vinyl of the Mazda 929. With its cabin windows peering out over the fence, the boat looked as if it was floating in a corrugated iron sea. Just as hundreds of other kids must have over the years, I'd stare at the boat and imagine it finally escaping its compound – raising its sails, ponderously angling out into the traffic, and gliding away.

When I moved back to Christchurch with my family in 2007, after twelve years away from the city, the boat came into view again. Along with the noble old Woolston Library and the dodgily restored mural on Bronski's dairy, it was a marker I'd tick off half-consciously on the daily bike ride from Mt Pleasant to the Gallery – something old and interesting to look at on a road whose eastern reaches have been eaten up by tilt-slab sameness. (Should the Ferrymead shopping centre ever require a motto, how about 'Where urban planning goes to die'?) After the big earthquake of 4 September, however, the morning bike ride became more eventful. There was a lot more to look at – or, depending how you come at the problem, a lot less. The first local demolition I saw up close occurred in the block just west of the big black boat, where a dairy and lawnmower repair outfit came down in a matter of days. I remember having a hard time deciding which was more shocking: how fast the buildings disappeared, how pathetically small the vacant lots looked, or how quickly I forgot what had been there. After the colossal shake of 22 February, empty lots grew so plentiful that I stopped even trying to remember what went where. Bronski's came down and so did the library – each new gap a glum rejoinder to the billboard further along Ferry Road that perkily announced 'The Christchurch I love is still here' ( just begging for a sarcastic 'yeah, right'). And then, one day in July, the boat was gone too.

For a while there I thought I was alone in wondering about the big black boat. No one was calling talkback radio and lamenting the subtraction from our heritage fabric. And, as far as I knew, the city's post-quake archaeologists weren't scouring the now-vacant property for evidence.

The most I could find in the newspapers was a short and not exactly fact-filled article in The Star for 14 July, describing the 'removal' of the yacht and the demolition of the red-stickered building on the same property. The article also told how police had escorted a man from the property for illegally beginning demolition work himself, but left it unclear whether the boat itself had been demolished. An email to the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority brought clarification of a kind: yes, the building had been demolished under S39, and the boat had been demolished too with the owner's consent, although he 'wasn't terribly happy about this'. A very different account had been posted on a message board on the TradeMe website, asserting that the demolition was high-handed and hasty; reportedly, the boat had been damaged during demolition of the adjacent building, leaving the owner no option but to assent to its destruction. But even if the boat was destroyed with good reason and full consent – and it seems clear, at least, that some tact and diplomacy were lacking – I found myself feeling strangely cheated by its disappearance. I wanted to keep on wondering indefinitely how the boat's story would unfold. The demolition brought that story to a premature end.

Reading further in the online discussions, I discovered I was far from alone in lamenting the boat's demise. An early post on a classic car website set the prevailing tone: 'OMG chch peeps! The big black boat is gone!' What fascinated me in these forums was the number of people with stories and memories to share – the way a portrait of the boat began to grow through rumour, hearsay and recollection. One person heard the boat was made by shaping a hole in the ground and lining it with ferrocement. Another heard that the wrong cement was used and the boat wouldn't float. Someone else said it had been bought for a dollar a few years ago by someone who installed a bar and a coal range onboard. Still another reckoned that the Transport Authority had refused a request to tow the boat through the tunnel to Lyttelton. Apparently there was once a website devoted to its restoration. The trustiest of these reminiscences came from a contributor to the Lyttelton Naval Club's e-newsletter, who recalled that the boat had been the dream project of a young English immigrant in the 1960s, who sold it on at a bargain price in the early 1970s. But I have to confess that, the looser and blurrier the stories became, the more I liked them. Someone recalled thinking it was the Ark, another that it predated European settlers. My favourite was the one about Peter Jackson having purchased the film rights to the story – a rumour that really ought to be true. And though a few people condemned the boat as an eyesore (it was, one correspondent hilariously suggested, lowering property values in the area), mostly the comments were affectionate and sane. It was as if, having begun as a piece of private property parked on its corner for whatever reason, the boat had been adopted, you might even say commandeered, by people whose visual space it overlooked. The boat seemed to have achieved the secret dream of all public artworks: it was everyone's.

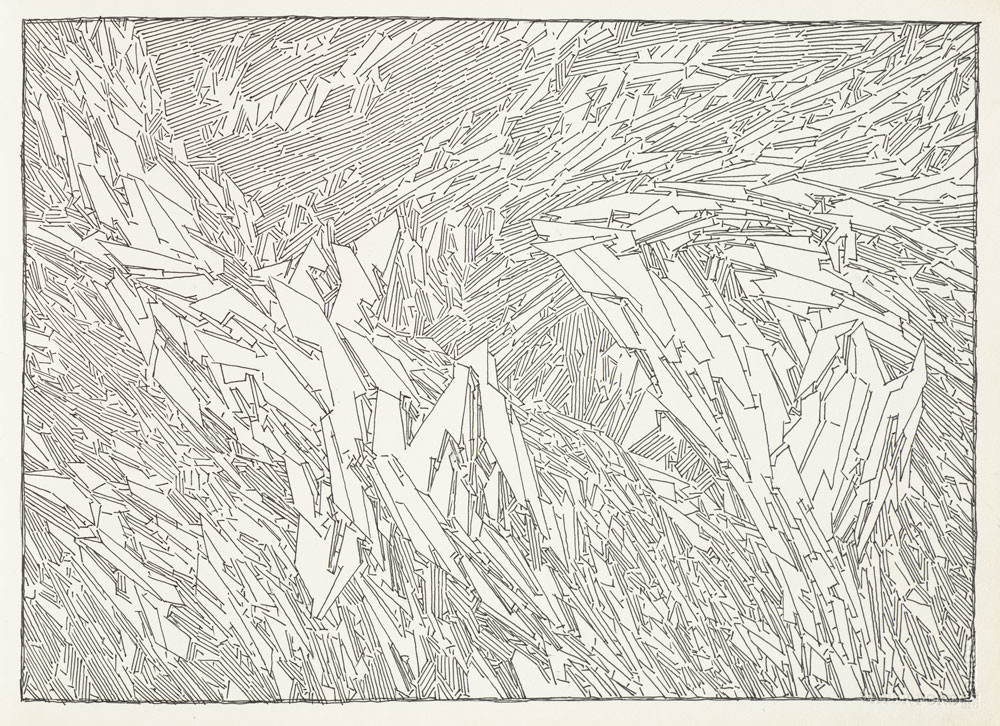

When it comes to public sculpture, the Where matters as much as the What. It's not enough just to have an interesting object, it has to be put in a place that enlarges its meanings. The problem with most public artworks is the absolutely predictable way in which the What and Where come together: things that look pretty much like public sculptures are planted pretty much where you'd expect them to go, and no one's heart beats any faster. Look around Christchurch and you'll find plenty of examples. Call them placeholder objects, middling monuments, the sculptural equivalent of screen-savers – works that fit in to their settings all too meekly and well.

The boat was a great work of accidental sculpture because it messed around with that formula. It was the right object in the wrong place. After all, a boat on its own is an evocative image: it suggests enterprise, the slow conquest of distance, the human ability to survive far from home. And boats carry all kinds of mythic and symbolic freight, from the Argo of Greek myth all the way through to the boat in which Max, from Where the wild things are, sails 'through night and day and in and out of weeks'. But when a real boat is beached in an unlikely place it becomes something more than a traditional symbol. It becomes a riddle or puzzle – a peculiar physical fact that demands, and maybe defies, explanation. Scrolling back through my own wholly personal list of memorable sculptural sights for the last half-decade or so, I'm surprised to find that beached and halted boats occupy a prominent place; I think especially of Mark Bradford's vast makeshift ark in the flood-wrecked ninth ward of New Orleans. Then there was Paul McCarthy's brilliant Ship of Fools in the 17th Biennale of Sydney, marooned inside one of the Walsh Bay piers like a mad fusion of convict ship and Christmas parade float. And then, locally, there was James Oram's Sea change in the 2008 SCAPE urban art biennial – a delicate yacht hoisted high by a crane above Cranmer Square, as if diagramming sea-levels in some globally warmed future. What all three examples shared with the big black boat was a tremendous sense of arrest. Boats move, it's what they're made to do, you can see it in their shape; yet in each of the examples just mentioned all that implied momentum had been suspended or brought to a stop. In its absence what built up was a kind of poetic energy, a productive confusion about where these vessels came from and where they were meant to take us.

As well as being out of place, the big black boat was wonderfully out of time. In an urban setting where the emphasis is overwhelmingly on 'development' and 'going forward', and where even small-time enterprises have adopted the corporate language of 'updating' and 're-branding', the boat just sat there getting stubbornly older. By rights it shouldn't have been there, but somehow it always was, and when objects stick around like that they become markers in our own lives: we measure time against them and they remind us who we were. Hence those affectionate memories in the online discussions – adults recalling their childhood awe. We don't feel the same affection for most public sculptures, because they're so clearly custom-built to outlast us – armour-plated against the efforts of vandals and the effects of time. By contrast the boat had a winning absurdity and vulnerability. It was a holdout, a rock in the stream, a ridiculous survivor. It was a reminder of the heyday of hobbyists and amateurs, when there were simply fewer products available to buy in this country. And it was also a reminder, much more distantly, of the city's maritime beginnings, when settlers fresh from the port of Lyttelton caught a boat across Heathcote River before making their way into the city along Ferry Road – so named for this very reason. To see the big black boat during rush hour, with cars pouring past, you could almost imagine it had been abandoned there long ago by some exasperated sailor and that the city had just grown up around it. As a public sculpture, the message it sent wasn't one of maritime success or human achievement. Instead it seemed to memorialise that other great human talent – for making big plans, discovering you can't fulfil them, and then getting distracted by something else. It was a slowboat, an ark of inertia, a monument to unfinished projects. (And a weirdly apt image for Christchurch in its current limbo state, as we peer into the city's future and think, Will this thing actually float?)

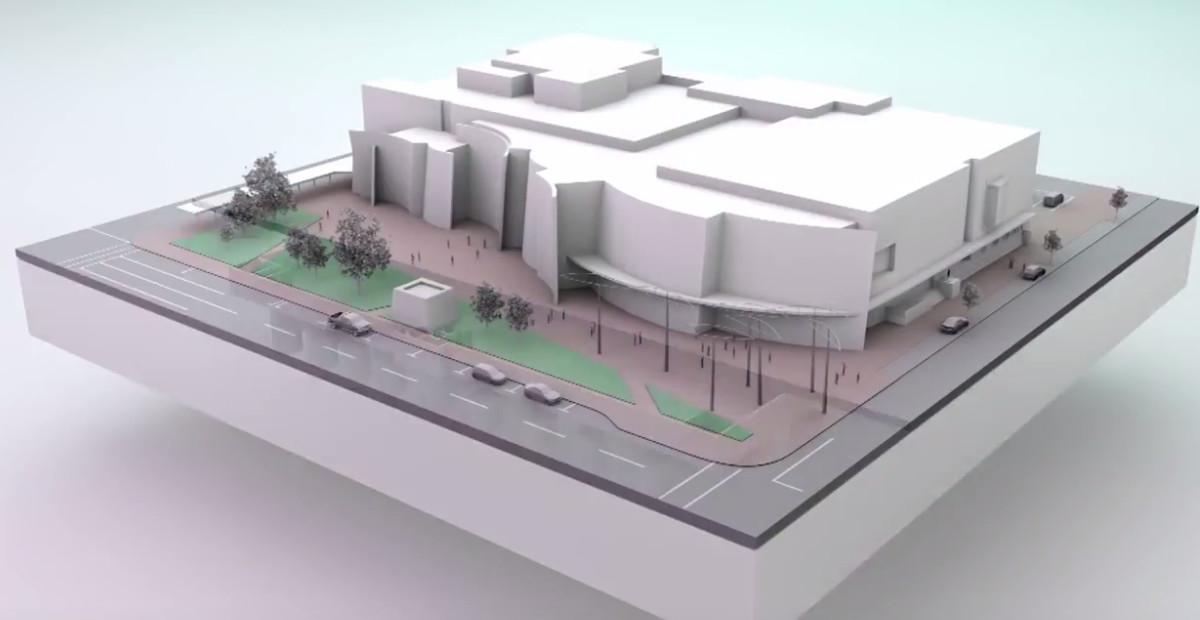

Am I claiming the boat as a major historic loss, akin to the loss of all those amazing old heritage buildings in the inner city? Not at all. It wasn't an 'icon' of Christchurch, it was just a part of it – one of the odd, eccentric and half-way intriguing sights that made travelling through the city more interesting. The point is not to play the minor sights off against the grand ones, but to recognise that they need each other – that the atmosphere of a city derives not just from its showcase buildings but all the textures and structures and minor-key sights that sit in the spaces between. As the city lurches between hard-core demolition on one hand (another day, another disappearance) and dreamy speculation on the other (the computer-rendered fantasyland of the Draft City Plan), now more than ever we need to remember the frictions and disjunctions, the accretions and juxtapositions, the collisions of materials and timescales, that make cities interesting places to be. Without them, I'm not sure a city is a city any more. I suspect it might just be a mall.

How is this going so far, do you think? Is it a little strange to be reading a homage to a ruined old yacht in pages usually reserved for important artworks? Maybe, but then these are truly strange days for art in Christchurch, and for public art especially. With so much demolition occurring all around us, and with so many normal art venues out of action, there's a powerful wish – it sometimes feels deeper than that: a need – to see art play its part in the so-called 'transitional city'. How might art show the way to a better future? How might it help to revitalise and revive? At times it has felt like sitting through one long and ardous brainstorm session, where the mood see-saws constantly between wide-eyed optimism and fits of the glums while Post-its flutter hopefully on every wall. There's talk of culture districts, mobile galleries and rivers of art; of monuments, memorials and more. And already there are things to see. The brilliant Gapfiller project demonstrates how well things might go; the dreadful 'lights of hope' show how badly (note to whoever is swinging the lights around like that: please stop – it makes the city look like an apocalyptic disco).

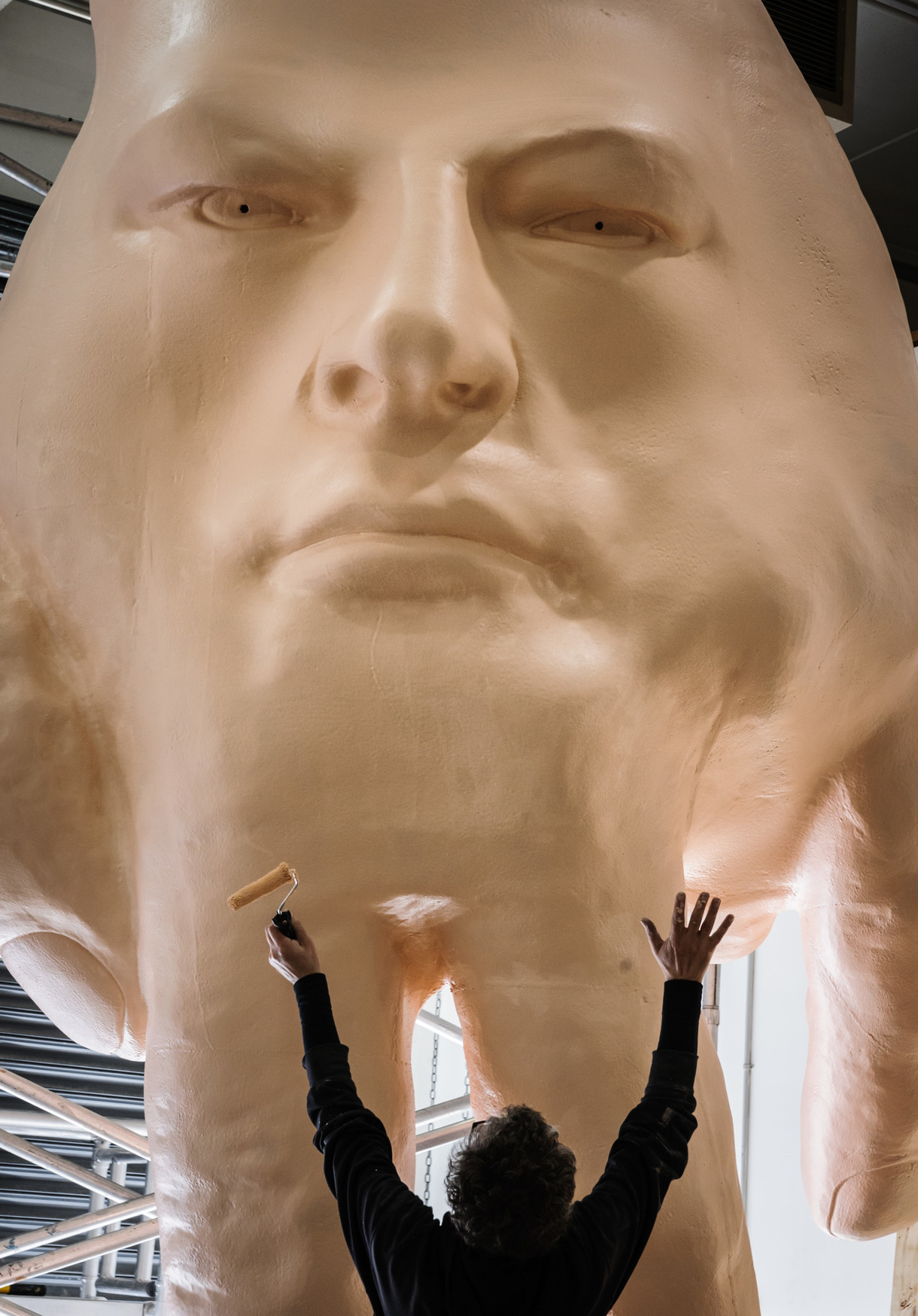

But it will be a very long time before anything resembling monuments or memorials makes sense in Christchurch. For public art of that kind to do its thing, it has to have a steady backdrop to stand out from. But steady ground is the last thing you'll find in Christchurch at the moment, because the ground has moved – and is still moving. The catharsis and 'closure' implied by monuments are all wrong for this moment, when the prevailing emotion city-wide – at least as I feel it – is not sober retrospection but some persistent mix of resignation, irritation, grief and ever-so-tentative hope. And then there's a strange but simple physical fact to contend with, which is that the city as it currently stands is its own memorial. The usual function of a memorial is to commemorate what's not there. But physical evidence of what we want to remember is still spectacularly with us; it is exactly what all those people walking the edge of the red zone have come in to the city to witness. There's not an art object out there that can compete in eloquence with all the instant ruins on view in the city – the walls, columns and other remnants left standing at the end of one day's work, and often gone before the next day is done.

The most telling monuments in Christchurch at this time are found, accidental, and emphatically temporary. They haven't been put there in response to the earthquakes and demolitions, but revealed or somehow brought to prominence by them. I'm thinking of the extraordinary relics and remainders that have been exposed in the process of demolition, like the hand-painted optometrist's sign my colleague Ken Hall photographed one morning on Ferry Road, staring out at the new gaps all around it. I'm thinking of the shell of the old Dowson's shoe store, again on Ferry Road, where demolition has revealed an incredible collage of colours, materials and textures. I'm thinking of the single stone doorway that was left standing, like a portal to nowhere, on the Carlton Mill site one night, and was no longer there a few days later. And of course, I'm thinking of the boat – yet another landmark I'd always expected to be there, and which has been turned into a memory, a ghost ship, by the quake.

Art gives us new things to look at – that's why we visit galleries. But in the process it also gives us new ways to look at things that are not art. With so many galleries closed and the city itself 'under destruction', perhaps the urgent task in Christchurch is not to find new art to look at, but to use art as a way of paying closer attention to what's going or already gone. Art as a frame or a viewfinder, an angle of approach, a way of exploring Christchurch off the grid and against the grain. Art as eccentric archaeology, a means of noticing and collecting, a way of remembering and recording what's not iconic. These moments of discovery and recognition will necessarily be personal and idiosyncratic; they might involve nothing more than a look, a pause, in the course of an ordinary day. What I like to imagine emerging, alongside the real memorials and monuments that will inevitably arrive, is a kind of museum without walls, a collection in the air, built on nothing more than rumours and strange affections, and containing as many rooms and spaces as there are people who care to remember.

One of those rooms will need to be big. I have a boat to store.