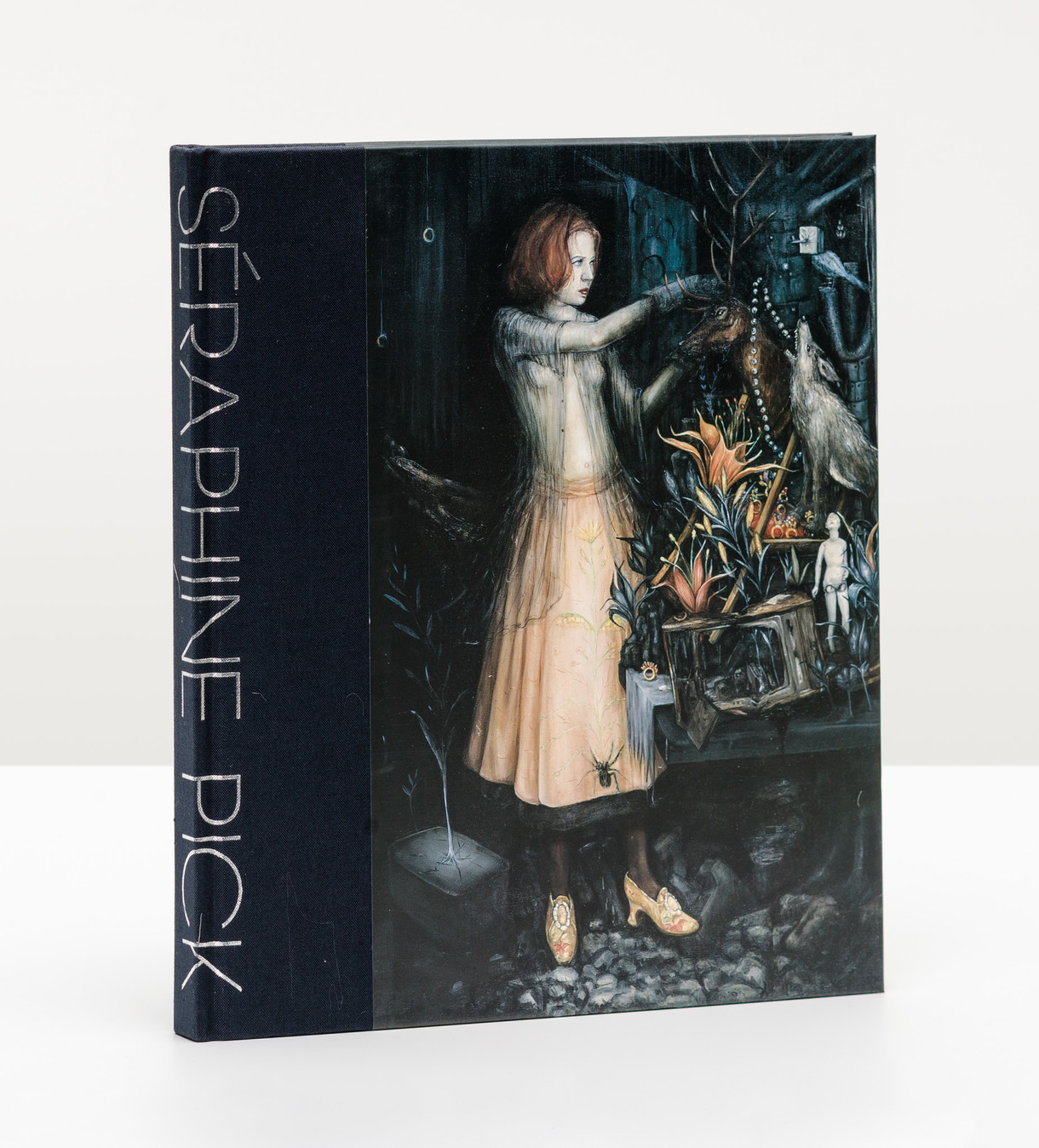

Séraphine Pick: assumed identities

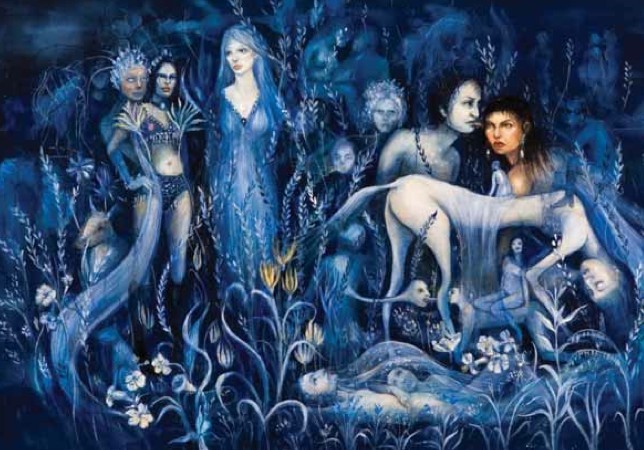

Seraphine Pick Untitled (Blue) 1999–2004. Oil on canvas. Private collection, Wellington. Reproduced courtesy of the artist

The celebrated faces gracing two of the paintings in Séraphine Pick's Brooke Gifford Gallery exhibition late last year wore expressions that were hard to pin down. Defensive, evasive and devoid of their customary charisma, the only thing they clearly conveyed was their wish to be somewhere – anywhere – else.

Perhaps that wasn't surprising, given that Pick's images of Elvis Presley and Janis Joplin originated in a series of famous police mugshots. Removed from that context and dropped into the comparatively elegant spaces of a commercial gallery - alongside a series of portraits that were, by contrast, poised and aloof – Pick's versions were both strange and familiar, like the strains of a well-known song performed by an unknown artist. Lined up against a wall and stripped of their microphones, stages and entourages, Pick's Joplin and Presley appeared as alternate versions – inadequate stand-ins for their former selves.

Like the real Charlie Chaplin, who once entered a Charlie Chaplin lookalike contest and did not even make the final, many of Pick's recent works have explored the creation of deliberately inferior replicas – the aura of star quality we associate with these figures has suddenly deflated around them, like a pricked balloon.

This subversion and sabotaging of identity is a recurrent theme for Pick, whose interest in portraiture is tempered by her fascination with the equivocal. Whether they depict friends, family, anonymous strangers or her own (continually altered) image, her paintings are seldom straight recordings of identity; instead her subjects often conceal much more than they reveal. In fact, it is the very act of obscuration that is at the heart of many of Pick's works – metamorphosing, turning away, wearing masks, sunglasses and hats, her players avoid the direct stare that we, their audience, offer them in a variety of amusing, ingenious and imaginative ways.

Pick's 1997 series Looking Like Someone Else included thirty-six small ‘portraits', none of which satisfy a conventional understanding of that genre. As with her recent works, the subjects were drawn from a variety of sources, including photographs, books and magazines, but also featured altered and blurred images of the artist herself. Far from offering us more information about the sitters, these tantalising images deflect us from every angle. In one especially intriguing ‘anti-portrait' a young woman refuses to face us, presenting instead only the back of her head and her bare shoulder. Robbed of the eye-to-eye connection we expect, we are reduced to studying the extraneous details for information; gleaning suppositions and half-truths from the bruise on her bicep, or the hint of a tattoo on her arm. This, of course, is Pick's point: identities are but a collage of a million individually inconsequential details, so the turn of a shoulder or a bluntly cut fringe become triggers that set our minds searching through the databanks for recognisable connections.

Early in Pick's career, commentators were keen to interpret her imagery as part of a tightly autobiographical narrative – a tendency that was undoubtedly reinforced by Pick's frequent inclusion of childhood references within her works. Despite her own collusion in this process, Pick was occasionally frustrated by the literality of these readings, which she believed could inhibit her audience's experiences of the works, discouraging them from bringing their own imaginations into play. With this in mind, it is perhaps no great surprise that her subsequent forays into portraiture and representation have been characterised by a desire to exploit and expose all possible ambiguities and uncertainties. Instead of removing any trace of herself from the works, she deliberately placed portrait-like images at the centre of many, then created such implausible and inventive worlds around them that it quickly became apparent that any idea of veracity or insight was being gently ridiculed. It is true that any viewer with the opportunity and inclination could still piece together a rich and racy storyline featuring the artist as its protagonist, but Pick's compositions so clearly fused imagination and fantasy with memory as to render any definitive ‘real-world' interpretation tantalisingly elusive.

Other works further disrupted the traditional order of portraiture, where it is expected that the subject will be a person of some significance or worth, or at least have some connection with the painter. Pick's portrait-like paintings were just as likely to prioritise nameless figures clipped in anonymity from magazines, or to home in on incongruous and eclectic details, such as a chihuahua so tiny it can be held in one hand. One unifying factor, however, was her interest in expression and psychological connection – for though her figures may hide behind hoods, paper bags and veils of blurred and scratched out paint, they are nevertheless distinctly animate. Though Pick has experimented with unpeopled landscapes on occasion, they are very much the exception rather than the rule. Indeed, she has often likened her painting to theatre, and has always been fascinated by the personas we adopt and discard in our everyday lives and relationships as well as the intricate negotiations and exchanges that take place between friends, lovers and families - the crossed wires, the ecstatic connections and the potential for danger and damage.

When enthusiasts of Pick's paintings discuss her work, their conversations reveal a sense of personal connection and involvement with the figures and situations she brings to life on the canvas. Her compositions may be alternately fantastical and out-of-kilter, but she also has an eye for those real moments where truth is demonstrably more compelling than fiction. However, it is Pick's interest in disrupting and subverting the anticipated relationship between the viewer and the imaginary painted worlds she creates that makes her one of our most interesting, and continually rewarding, artists. Like that moment in an airplane flight just after take-off, when the houses, roads and fields of the landscape below lose their immediacy and become like the features of an architectural model, her creations are familiar, but not completely so; recognisable, but becoming less clear with every second. If we are lucky, the real world surrenders its hold and we are invited, temporarily, into a world that is a captivating concoction of artifice, experience, invention and memory.

Felicity Milburn

Curator